Joe: Alright, let’s do this thing. Adri, you and I had planned to cover at least two more categories this summer than we actually did and had hoped to cover even more than that. But, you know, life is hard and schedules are harder and we just didn’t quite get there.

By the time this chat will go live Hugo voting will have closed, and if I’m being perfectly honest with our faithful readers, Hugo voting will have closed before we finish this conversation as well. And you know what? That’s okay! Hugo reading and Hugo chatting is supposed to be fun and is, in fact, fun and we should get on with it.

Adri: Hugo voting has closed as I write this. Life does indeed get in the way of SFF reviewing and Hugo conversations, and that’s something we all have to live with.

That said, this has been a really good year for me in terms of actually reading and watching Hugo things - with the exception of one series (For All Mankind) in BDP short and a few volumes in Best Series, I actually got to pretty much everything on the ballot

Joe: This is going to be a lot less focused than our specific category conversations because there we’re talking about, well, a specific category. I expect we’re going to be all over the place here because there are categories I didn’t quite finish reading / watching everything for (sorry Dramatic Presentation Short Form and Lodestar Awards) and at least one more where I just don’t have anything constructive to say for various reasons that we discussed offline that I don’t think would be productive for anyone to bring online. That’s vague for our readers, but it’s probably the right decision.

Where I think I want to start is with the Lodestar Award, which I just admitted to not finishing. I do plan to read the ones I haven’t gotten to you but I still wanted to highlight Iron Widow, Chaos on Catnet, and Victories Greater than Death. It’s only half of the category, but what a lineup!

Iron Widow absolutely blew me away. The novel wasn’t on my radar at all and I could not put it down once I started. I think I read it in three sittings, maaaaaybe two. It’s one of those books where you pick up any time you have a spare minute and just keep going well past where you planned to stop and forget about normal sleep schedules. Loved it. Adored it, for all its brutality.

Adri: Iron Widow was a very easy favourite for me in this category too - it’s one of three of my nominees to make the final list. That said, there wasn’t much between the four other YA works for me - Chaos on Catnet ended up as my fifth choice but I enjoyed reading it just as much as Redemptor, which was my second. Apart from Iron Widow, the only other easy choice was ranking The Last Graduate 7th out of 6 - not because I didn’t enjoy it (I did, far more than I expected to) but because it’s an adult novel and I would like this YA award to be subject to at least that basic level of curation.

Joe: Iron Widow is Xiran Jay Zhao’s debut novel, which also finds her on the Astounding Award ballot for Best New Writer and that, THAT is a murderers row of up and coming writers. Actually, scratch that. It’s a murderers row of writers who are already here. I hate to make a reference to a 34 year old movie, especially given that the context is that the person saying the line is a bit of a dumb ass about it, but everyone on on that Astounding ballot has announced their presence with authority. These are the writers to pay attention to. Not next, but right now. Xiran Jay Zhao is the real deal and so is everyone else on the Astounding ballot.

Seriously - Shelley Parker-Chan is up for Best Novel for She Who Became the Sun, which is is an absolute tour-de-force. I was enthralled last year with Legendborn from Tracy Deonn. A.K. Larkwood’s The Thousand Eyes was one hell of an epic fantasy debut. Most recently I finished Winter’s Orbit by Everina Maxwell and oh, my heart! I’m not going to compare year over year finalists, but this, this is a group of new writers that I’m excited to follow over the next decades.

Adri: I’m a little sad every year we don’t have short fiction writers on the Astounding Award ballot, especially in a year where I don’t think there are any Astounding eligible authors on the novelette and short story ballots (side note: go look up fiction from Kel Coleman, Filip Hajdar Drnovsek Zorko and P.H. Low and be amazed, please) but I can’t fault any of the writers who have ended up on the ballot this year. Winter’s Orbit is wonderful, Legendborn is an absolute gem, and The Space Between Worlds didn’t get nearly the level of recognition it deserved. And The Unspoken Name has Csorwe and Tal’s toxic workplace dynamics, which is a recommendation all on its own. As you say, these are writers who have already had a big impact in genre and while there is, of course, bias towards long form writing in the kinds of books that get that buzz, it doesn’t make this list of authors any less awesome. Or, if you will, Astounding.

While we’re on the subject of long form fiction, let’s talk about the longest form of them all: Best Series! (Note: this was a less contrived link than trying to go through Ada Palmer’s past Astounding win). I was happy to start with a decent chunk of these already read, and I only really had to form new opinions on two series: World of the White Rat, and Merchant Princes. Three world-hopping thrillers later, and I’ve confirmed that my dislike of the Laundry Files sadly stretches to all of Stross’ work - there’s nothing I think is particularly bad (aside from a couple of dated 2000s moments in the early books), but absolutely nothing I cared to read on for. And then there’s World of the White Rat, which is actually an ongoing fantasy romance series, a quest-y duology and a standalone all bundled together in the same trenchcoat. It’s T. Kingfisher, so it’s excellent (the romance involves the leads being a little too dense for my liking, but still great), and I’m looking forward to reading the remaining two books I didn’t get to, but it hasn’t troubled my absolute favourites at the top of the category: The Kingston Cycle and The Green Bone Saga.

And, like, you’ve expended a lot of words about this endless debate on how Best Series “should” work, and we’ve spoken about it before, and no doubt that debate will get plenty of airplay at the Chicago business meeting, but overall - and despite having one series I don’t care for (Merchant Princes), and one I’ve got mixed feelings about as a series despite loving some individual works (Wayward Children), I just think that this is a great ballot in a great category, and the inclusion of two of the most groundbreaking trilogies of recent SFF, works which haven’t had individual Hugo nominations despite being decently recognised in other awards, really proves the value of Best Series for me. More importantly, these works don’t need special measures that artificially take other authors out of the running to get that recognition. I assume Ada Palmer’s Astounding win wouldn’t take her out of contention for the Terra Ignota series, but it also belongs here and the fact that the first volume has the possibility to win a Hugo back in 2018 doesn’t lessen the excellent (and bizarre) things she did with the series after that first volume.

Joe: Series is an interesting one for me. I didn’t read Terra Ignota because I bounced off the first book and never had the desire to give it another shot to find out if it was the book or if it was me or even just where I was when I tried the first book. I could write an essay about my relationship with Charles Stross’s fiction - but I’ll simplify and say that it’s very hit or miss and for the most part his Merchant Princes series and the Empire Games follow up series was a solid read but never quite came together to be something great.

I am absolutely with you on the top of this category, though - The Green Bone Saga and the Kingston Cycle are really the cream of the crop. In particular, The Green Bone Saga is really something special - one of the best new series I’ve ever read and I’d put it right up there with the most notable series of recent years, and I’m talking the Imperial Radch and The Broken Earth levels of good.

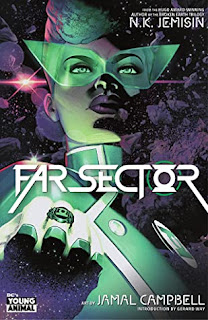

I’m generally happy with the finalists for Graphic Story, though I only *just* got a copy of Strange Adventures from the library now that voting has closed. I’ve never been interested in Green Lantern, but I certainly wasn’t surprised that I liked N.K. Jemisin’s Far Sector. The biggest surprise for me, though, is Lore Olympus. That’s a book and series I want to read more from.

Adri: I had the opposite reaction to Lore Olympus, unfortunately - I was interested in checking it out, since I used to be really into webcomics back in the 2000s and I’m intrigued by the apparent resurgence of webtoons which now seem to fill that niche. Unfortunately, I’m not the right audience for “physically tiny, naive, vulnerable woman attracts the attention of much more experienced, more powerful guy”, and I found the execution of Lore Olympus to be irritating and occasionally the wrong side of creepy. This isn’t me making some grand point about “problematic” romance power dynamics, since all the characters are immortal gods and all, but it’s very much not for me.

Then we’ve got Monstress, which I enjoy very much but is enough of a Hugo fixture that I’m not super excited to see it on the ballot again, and two Kieron Gillen-written comics which are also later issues of previously nominated series. My issue with Kieron Gillen, I have established, is that I quite like his premises in theory, but the particular brand of bleakness and horror-tinged action that he brings to the execution are really not my jam.

That leaves the two DC comics, and here’s where I was really blown away. No thanks to DC itself, I add - neither of these works were made available in the voter packet and I had to spend a lot of effort tracking them down in different London libraries - but, as a non-superhero reader with minimal prior exposure to DC properties in particular, I was really blown away by how good and accessibly written both of these were. Jemisin and Campbell’s Far Sector was a particular favourite: a take on a new Green Lantern who takes on a mission in a very far-off part of the galaxy where three species of alien are keeping up a fragile truce, it combines great worldbuilding, an intriguing mystery and a Black woman hero whose past is rooted in the USA’s current race politics and who draws on that experience to interesting effect. And Strange Adventures - featuring Adam Strange, a character I knew nothing about before now - takes apart a particular “boy’s own” portal fantasy-type adventure trope with scathing precision, with Strange trying to maintain a particular, highly colonial, image of his military victories on the planet Rann as Earth begins to suffer its own invasion, and those around him start to notice his story doesn’t add up.

Joe: I have perhaps less to say about Related Work, but I was incredibly impressed with Abraham Riesman’s True Believer. I won’t go so far as to say it was a takedown of Stan Lee, but it was a revealing of who he was and consolidated a lot of what was out in the world into one book where readers who are not fully engaged in all the dealings with comic books and its history might have missed - the Stan Lee story is far more complicated and ultimately tragic that I think most readers would have expected. Certainly it was more than I had ever known.

Adri: True Believer really surprised me too - I read it far quicker than I was expecting to, and it shone a light on a figure I’d never known much about, beyond that he was “the nice old man who did all the movie cameos”. The reality is, as you say, far more complicated, and full of a lot of tragedy for Lee himself and sadly also for a lot of the people who worked alongside him. On the whole, I enjoyed everything on this ballot - Charlie Jane Anders’ Never Say You Can’t Survive, which I read in audiobook, was a real highlight (Anders comes across as such a great person to have in your parasocial corner), and I was impressed by Dangerous Visions and New Worlds as well. This is a very non-fiction and memoir heavy ballot after the “a bit of everything” ballots of the last few years, and while I hope we see a return to broader nominations (there are some great video essays that would have fit well amongst the works here), this is the first all-written BRW ballot that I’ve been able to read everything in, and I think this is a great list in itself.

Joe: Regarding the fan categories, our own Paul Weimer is up for Fan Writer again for the work he has done here at Nerds of a Feather and pretty much everywhere else because Paul is ever-present in genre fandom. If my count is correct, this is third time on the Fan Writer ballots and he has also thrice been formally on the Fancast ballot for The Skiffy and Fanty Show.

I would be more than thrilled to see Paul pick up a Hugo, though as with most years this is a very impressive line up of fan writers. In particular, I am most familiar with the writing of Jason Sanford through his investigative Genre Grapevine columns and also with Chris Barkley, who is another of those writers and individuals we see in many fan spaces.

Adri: Plenty of wonderful folks to choose from this year, as always, and I’m not going to express any preferences! But I’m particularly thrilled to see Alex Brown here, which I think is largely for their writing at Tor.com. I don’t want to derail this chat into another Hugo politics subject, but I’m very much opposed to attempts to define fan writing as “strictly no money involved”, because it doesn’t match the realities of how good fan critique is made and published these days. From paid zines like Tor and Locus, to individual artist Patreons, I think it’s not just valid but actively important that writers who can’t, or don’t want to, give their labour for free are nevertheless recognised as fan creators in the way that I think is most important - that is, people offering critique and reactions and recommendations and generally keeping a community alive around works that they love.

Joe: In Fancast, I am beyond thrilled for Hugo, Girl - more than anyone else, I might have actually cheered out loud when I saw they are on their first Hugo ballot. I love their podcast, it’s one of the few I make a point to listen to the day it drops on my podcatcher of choice - and I got to meet Lori and Kevin at Discon last year and they were absolutely delightful to share a meal with. I also immediately pushed my Hugo at Lori following the Hugo ceremony last year because I was mentally staggered by how heavy the thing was and needed other people to share in that weight. But really, Hugo Girl is just about my favorite podcast these days and they would be an eminently worthy recipient of a Hugo Award.

Adri: Hugo, Girl is excellent, and like you I’m so glad that they’re represented this year!

Joe: The Coode Street Podcast is another favorite of mine and I was thrilled for Jonathan Strahan and Gary Wolfe to win after 8 times on the ballot (it’s 9 this year). That’s another can’t miss podcast for me. Likewise, I’ve come to appreciate Octothorpe this year. I believe I started listening after the Hugo ballot was announced, they just hadn’t hit my radar yet - but they are a very fan-community focused podcast (that also talks about various books and media). Good stuff, there.

We’re not on the ballot for Fanzine this year, and you and I have discussed previously about how it is weird and privileged to say that it is and was refreshing to be able to engage with the Hugo Awards without being a part of the Hugo Awards (though I certainly hope to be a part of the Hugo Awards in the future) - and that’s where this is a fun category to think about - though these are also our direct peers and and the relatively few of those peers who I have met have been collectively wonderful people, so I also don’t want to do any sort of a deep dive on our friends.

The only previous winner on this ballot is Journey Planet, though I had to double check that it wasn’t Journey Planet’s win which led to an acceptance speech being on the ballot the following year for Dramatic Presentation Short Form and it is not, I’m thinking of Drink Tank’s acceptance speech - though both Drink Tank and Journey Planet are led by Christopher Garcia and James Bacon so at least that was a reasonable error to make (Journey Planet also has a larger editorial team for each issue, if I’m being accurate). They’re quite good.

This is either the last year or the next to last year that Quick Sip Reviews can be reasonable recognized by Hugo as Charles Payseur is now reviewing for Locus and, I believe, attempting to step back from the prodigious writing pace he has had at Quick Sip. I should note that Charles used to write for Nerds of a Feather, though his nominations over the years for Quick Sip and as Fan Writer are all his own. He has carved out a unique and particular and beloved space as a short fiction reviewer and champion and has earned each one of his nominations. I’m also biased.

Alasdair Stuart is a force for good in our community and his Full Lid that he edits along with Marguerite Kenner is excellent, and one of the few newsletter fanzines to catch on with Hugo Voters (along with Jason Sanford’s previously mentioned Genre Grapevine and The Rec Center a few years ago).

I am a big fan of what Olav Rokne and Amanda Wakaruk have done with The Unofficial Hugo Book Club Blog and Olav’s presence and writing on twitter, I think, is intrinsically tied up into the identity of the blog. I have also shared a meal with Olav and Amanda, and they were likewise delightful.

I am less familiar with the work of Galactic Journey and Small Gods, though I was more familiar with what Galactic Journey has done as a concept (and Gideon Marcus has also published two Rediscovery anthologies shining a spotlight on the women science fiction and fantasy writers of the 1950’s and 60’s, similar in concept to what Lisa Yaszek did with her seminal The Future is Female anthology - and while those anthologies don’t have anything to do with what Galactic Journey is eligible for in regards to, they do add to the zine’s reputation in my eyes). Small Gods is a, well, smaller project from Seanan McGuire and Lee Moyer. It’s quite different from what we tend to think of as “fanzines” but it is a fun little quirky tumblr with blips of stories from McGuire and beautiful art from Lee Moyer.

Adri: I don’t have anything to add to your summaries, except that it’s nice to see a fanzine ballot where I go “there’s some great stuff in that category” even without me being specifically in it. I’m not terribly keen on Small Gods being here, because, again, I would like to see “fan” categories recognise people who build conversation and support a critic community in genre, and I don’t see this project as doing so in the way that all five others do.

As to my personal choices, I would really like to see the Hugos give some well deserved recognition to The Full Lid or Quick Sip Reviews. Both are labours of love done by people who are constantly putting good things into the community, and I’d love to see Charles win for the tireless work he does for short fiction reviewing AND also I would like Alasdair’s force for good, as you put it, to be recognised and rewarded and for fanzines to put a newsletter winner into the mix of “things a fanzine can definitely be”. That said, I’d be happy to see any of the non fiction zines take this home, and I’m hopeful that whoever wins, it will be based on the merit of their work and not on the rather uneven star power that Seanan McGuire’s nomination brings to a usually lower-voted-on category.

Joe: Unless there’s anything else we need to dive into, I think that wraps up our final Hugo chat and just in time before the Awards are given out. One category that we missed was Novelette, for which I heartily recommend Oghenechovew Donald Ekpeki’s “O2 Arena”.

Adri: I forgot we didn’t cover Novelette, but that’s very much seconded! I hope that everyone attending Worldcon this year has an amazing time, and I will eagerly await the Hugo announcements so we can start reacting and, even more excitingly, creating reading lists for next year’s fun.

Joe Sherry - Co-editor of Nerds of a Feather, Hugo Award Winner. Minnesotan. He / Him

Adri (she/her), Nerds of a Feather co-editor, is a semi-aquatic migratory mammal most often found in the UK. She has many opinions about SFF books, and is also partial to gaming, baking, interacting with dogs, and Asian-style karaoke. Find her on Twitter at @adrijjy