And so we come to his second novel, Wearing the Lion.

If you are at all familiar with anyone in Greek mythology, you probably know something about Heracles (or, if you want to go Roman, Hercules). Having a TV series devoted to him in the 1990’s certainly helped. His labors come up (even if why he had to do the labors sometimes is fuzzy in the minds of many people). His prodigious strength, certainly is the stuff of legend. He is really is the OG superhero of Classical western literature.

And then there is of course the monsters in Heracles' story, where Wiswell comes in.

In many stories of his even before his breakout novel, John Wiswell has been writing and thinking about monsters¹. Monsters are one of his core themes and ideas and exploring monsters, from the inside as well as out, is one of his strongest power chords. And Heracles’ story, let’s face it, is positively littered with monsters. Nearly all of his labors are capturing or killing something monstrous. Probably, the most famous of these is the Nemean Lion, the one whose hide is impenetrable to weapons. How do you defeat a monstrous carnivore you can’t hurt with a spear or a sword? In the main line of the myth, Heracles wrestles it to defeat, uses its own claws and teeth to cut the hide, and then wears it for the rest of his life as some rather good light armor.

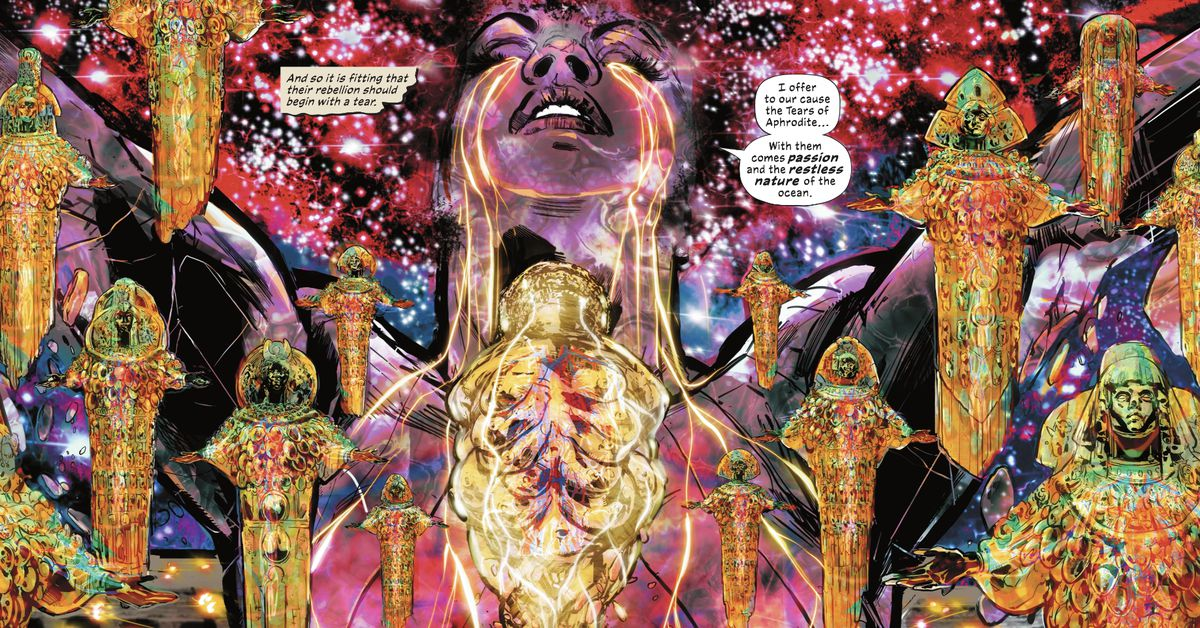

Wiswell comes up with a rather different idea, and hence the book’s title and the throughline for the book. Why would Heracles, himself a monster in some ways, not seek to befriend monsters rather than to slay them? And what does that do to his myth and story? The Nemean Lion is the first, but far from the only monster that Heracles meets and befriends in the course of the narrative. Heracles is not afraid of a fight, or of war, but this is a Heracles that would rather make a friend. Again, and again. Wearing the Lion is not an act of violence... it is an act of love.

The book alternates point of view between Heracles and Hera. You might be familiar that in most myths, Hera hates Heracles and from birth tries to kill or weaken him². Wiswell plays on the fact that while Hera hates Heracles (for being a bastard son of her philandering husband Zeus), Heracles himself is for most of the book absolutely and positively devoted to “Auntie Hera”. He takes the “Hera’s Glory” of his name (that is what his name means) and hits that theme again and again. This imbalance between a Heracles who is always trying to live up to his divine stepmother and be worthy of her, not knowing she is seeking his downfall, drives a lot of the plot, and some of the more mordant humor of the book. There is the damoclean sword hanging over the narrative--what happens when Heracles finds out what Hera really thinks of him?

But the book begins lightly and sprightly enough, in a style that I’ve come to associate with Wiswell’s writing. It almost, I think, strays over to being twee. The conversational tone of the chapters contributes to this, as we often have Heracles, or Hera, talking to (or even more often addressing ) another character in the chapter. The second person point of view gets a workout in this novel and uses it frequently

For all of that rather light tone at the beginning, though, Wiswell is willing to go dark, and in fact to tell his story has to go dark.. I should not have been entirely surprised given his short fiction but there is definitely a gear shift in this book, before and after the death of his children. I had wondered, being relatively familiar with the Heracles story, how Wiswell was going to go there, since he changes a lot of the rest of his labors and background. But indeed, Heracles does in fact kill his three children thanks to a bout of divine madness. What had started as a relatively light Heracles and the monsters story shifts into a more serious and somber tone with less humor and more drama. Heracles of course wants to know why this happened, convinced some god must have done this, and so the rest of his narrative shifts to the quest to find that out.

There is also good work on the theme of identity and who you are. The fact that one of Heracles’ early names Alcides is used again and again, and Heracles reverts to that name when he feels no longer worthy of the name Heracles. This reminds me of Doctor Who’s The War Doctor, stripping himself of the title Doctor, and having in his own mind to re-earn and regain the right to use that name. Lots of Wiswell’s characters at some point have crises or have to come to terms with who they are and their nature. His take on Heracles is another in that spirit and mode.

Meantime, on the other side, Hera has reconsiderations of the fallout of what she has done. A strong beat Wiswell hits again and again is that Hera is Goddess of the Family. Families, especially pregnant mothers but all families in general, are her divine mandate. And instead of killing Heracles with the madness, she wound up killing his family instead³. Coming to terms with all that and what happens next, along with Heracles’ own quests, makes up the back portion of the book. And as Heracles befriends more monsters and completes more quests, the eventual conflict of Hera’s plans and Heracles’ own quest head toward inexorable conflict.

So the novel is really in the end about Heracles and his found family of monsters and how they intersect with Hera and her family of gods and goddesses. There is a lot of lovely bits set on Olympus with Hera and the parts of the Olympian pantheon we see--in particular Ares and Athena, although a couple of others come in as well. A criticism I might have for the book is that a few opportunities were definitely missed on this side of the equation, especially with Hera given the divine mandate of motherhood and family being an important theme of the novel. Demeter and Persephone for instance, aren’t even named. The wrangling between the deities we do get and see, however is gold, and their squabbling never gets old⁴. The novel really is, from Hera’s perspective, the slow realization that Heracles’ group of monsters with him are, in fact, a family. Heracles’ story is the slow realization of his own nature, what he did, and coming to terms with himself. And, not to bury the lede, learning to actually accept his family for and what they are.

Wearing the Lion shows off John Wiswell’s talents for humanizing and making monsters into people and again, like his first novel, showing that people can often be the real monsters of society. This book doesn’t quite hit that theme as hard as Someone You Can Build a Nest In, this novel though is much more about building and creating a found family...and accepting them and accepting them and their love into you, as much as you loving them. Heracles gets the latter part right off... but he (and Hera) need to learn the first half of that equation matters, too.

Highlights:

- Interesting take on the Heracles myth exploring his relationship with Hera in a new way

- Strong theme of found family of monsters

- At turns funny, mordant, and without warning, will tear your heart out (a John Wiswell book in other words)

¹Dream conversation at a con or literary event ? Get John Wiswell to talk to Surekha Davies (author of Humans A Monstrous History) about monsters. That’s box office gold.

²As Fry notes in his books, though, there are a multiplicity of varieties and variants to Greek mythology. Heracles' story is no exception and in fact, he was enormously popular across the Mediterranean. Heracles is actually Hera’s chosen champion in Etruscan mythology and we get none of the “try and kill him” business.

³In this version of the myth, Hercules kills his children but not his wife, who remains loyal to him and important to his redemption. Is that “correct” to the myth? See footnote 2.

⁴Allow me once again to lament the cancellation of KAOS, with Greek Gods set in the Modern Day.

POSTED BY: Paul Weimer. Ubiquitous in Shadow, but I’m just this guy, you know? @princejvstin

.webp)