Today’s Mind Meld question is the following...

What is your favorite winner of the Hugo award for best novel? Why?

Charlie Jane Anders is the Hugo Finalist co-host of Our Opinions are Correct, as well as the author of All the Birds in the Sky and The City in the Middle of the Night.

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

This is my favorite Le Guin novel, and I think about it all the time. The story of a physicist who travels from a dirt-poor socialist anarchist world to a decadent capitalist one, this book asks so many important questions about money, property, scientific progress, and the balance between the individual and society. And even better, it doesn't really give us any easy answers. Le Guin probes the flaws in both Urras and Anares with great precision, while managing to make both worlds feel real and lived-in. And when you read all of her Hainish novels and stories in one go, as I highly encourage you to do, you start to realize that this novel's hero, Shevek, has an impact that extends far beyond these two worlds --- Shevek invents the Ansible, a instantaneous communications device that provides a crucial plot point in many of the other Hainish stories. The natives in Le Guin's "The Word For World Is Forest" are only really saved because of an Ansible, and it also helps in many other stories to provide a crucial connection to the wider universe. For all its focus on the fate of two worlds and the never-ending clash between ownership and collectivism, The Dispossessed ends up being a story of how technology can connect us to many other worlds and help us to realize that we're all connected.

Casey Blair writes speculative fiction novels including the cozy fantasy web serial Tea Princess Chronicles, which is available online for free. She lives among the forests of the Pacific Northwest and is most frequently found trapped by a cat. Follow her on Twitter as @CaseyLBlair, or visit her website at caseylblair.com.

On one hand my answer is N.K. Jemisin, particularly The Stone Sky for the glorious, visceral thrill of such a brilliant author and series being uplifted by the voters to stick a metaphorical finger in the eyes of racist naysayers by winning three times in a row. Every book in the Broken Earth series is unflinching, and reading the truth Jemisin lays bare in it and knowing people have recognized the value of her work is incredible. It was a powerful series to read, and it was powerful to see it win every single time.

But for me it is also Lois McMaster Bujold's Paladin of Souls, which was my first encounter of a fantasy book that centered an older woman and mother who still gets to experience adventures. Bujold's work is always stunning, but this one in particular mattered for me to read: among a great deal of heavy narrative lifting, it was also a dream of a future for women where we exist, and are relevant, and can have fun past our early twenties or past bearing children. Reading that masterfully wrought story and realizing how rare this aspect was and is in our fantasy changed how I thought about the genre, the world, and what it mattered for me personally to do in both.

Cheryl Morgan is an editor, critic, publisher, radio presenter, occasional writer of fictions, and

possibly a few other things that she has forgotten. Most of her writing can be found via her blog,

Cheryl’s Mewsings and she is on Twitter as @CherylMorgan.

I have often been asked to pick my favourite science novel. That’s not an easy question, but it is actually easier in some ways than picking my favourite Hugo winner. After all, people rarely agree on which novel is the best of the year. If they did there would be no point in having the Hugos. So in many years my favourite book fails to win the Hugo. Indeed, quite often it doesn’t even make the final ballot (Cathrynne M Valente’s Radiance being a case in point). As a result, the exercise of picking a favourite Hugo winner becomes more a matter of picking a favourite among a bunch of books that I thought were a bit meh, or even actively disliked.

Thankfully there are some years in which books I did like were winners. I still have a soft spot for China Mièville’s The City and The City, for example. I also love Ancillary Justice, and the whole of N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy. (Are the Hugo winners getting better, or at east coming closer to my taste?) But I’m slightly nervous of picking something recent in case it doesn’t pass the test of time.

A case in point is William Gibson’s Neuromancer. It is a book I loved when it came out. It also

kickstarted the entire cyberpunk genre. It is clearly a very important book. But is it still a favourite, now that we live in a world in which cyberspace has proved very different to the one that Gibson imagined? The real internet is far more like something out of Pat Cadigan’s Synners than out of the Sprawl Trilogy. Of course, there are also books that I haven’t read. And there are books that I read so long ago (The Demolished Man, for example) that I have no idea whether I still like them or not. I have this year’s Hugo reading to do, so I’m not going to be re-reading the backlist for this project. So where does that leave me? Well, there are a handful of absolute classics of the genre on the Hugo Winner list, and among those I am fortunate enough to find one of the books I often mention when people ask me for my all-time favourite science fiction novel. That book is The Dispossessed by Ursula K Le Guin. What is so special about The Dispossessed? Well to start with it is by Le Guin, who is as close to a genius that our genre has produced (and note that Gene Wolfe did not win a Hugo with any of his novels, nor did Octavia Butler). But the main reason I love it is that it does a thing that many science fiction novels try; and does it superbly well. The Dispossessed is a Utopian novel, harking all the way back to Thomas More’s original. Whereas More’s Utopians dig a channel to separate themselves from the mainland, the people of Anarres have gone to live on an entirely separate world. They have, in classic Utopian manner, tried to create a perfect society. And, just like everyone else who tries this, they fail. Le Guin understands that one man’s Utopia is another man’s Dystopia. What suits some of us does not suit all of us. Also, humans are naturally competitive, and any attempt to create a totally egalitarian society is doomed to failure. Someone will always find a way to make themselves seem better than everyone else, even if that is only “better” by their own definition. As a result, The Dispossessed is less of a political polemic and more of an extended analysis of the merits and demerits of different forms of social organisation. It is a book that debates with itself, and makes a very good attempt at doing so neutrally and fairly. Obviously there are those who think that the book is a stunning portrayal of the evils of Capitalism, and others who think it is a stunning portrayal of the evils of Communism. I think both of those groups are wrong, and I think Le Guin would be disappointed in their reaction as well. This attempt at a balanced political analysis puts The Dispossessed head and shoulders above so many other science fiction novels that have attempted to portray utopian societies. (I’m thinking in particular of Sheri Tepper who kept trying to enforce correct behaviour by various sorts of mind control.) I wish there were more books out there that admitted that they don’t present a solution to problems of mankind, and indeed that no such solution is possible. People are individuals, cultures are individuals. Attempting to impose a one-size-fits-all solution will always be a disaster for a lot of people. We need that lesson more than ever right now.

Elizabeth Bear was born on the same day as Frodo and Bilbo Baggins, but in a different year. She is the Hugo, Sturgeon, Locus, and Campbell Award winning author of 30 novels and over a hundred short stories, and her hobbies of rock climbing, archery, kayaking, and horseback riding have led more than one person to accuse her of prepping for a portal fantasy adventure.

She lives in Massachusetts with her husband, writer Scott Lynch.

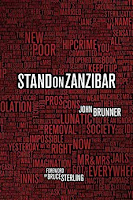

“Favorite" is a hard question, and probably changes depending on my mood. But I can tell you the most formative one for me, which is John Brunner's STAND ON ZANZIBAR, a dazzling and difficult novel that manages to be cyberpunk before cyberpunk was a thing. I read it when I was very young, and I've reread it at intervals since. The actual metric of whether science fiction is any good or not is not whether it manages to predict the future, and yet STAND ON ZANZIBAR and its companion novel THE SHEEP LOOK UP manage to predict algorithm-targeted advertising, fake organic food, spree killers, and a number of other issues that feel pretty relevant today. Stand on Zanzibar is very concerned with overpopulation as an "if this goes on" kind of issue, which sometimes makes it feel a little dated, but the concern with corporate control of media, fake news, and the management of what people think and feel through information siloing are eerily prescient.

The book's written in a non-trad format that was radical enough for its day that there's actually a note at the beginning explaining how to read it, but any modern reader who can handle recent Hugo-winning novels (or Alfred Bester or Ursula Le Guin, for that matter) won't find it too daunting, I think.

Michael J. Martinez has spent 20 years in journalism and communications writing other people's stories. A few years ago, in a moment of blinding hubris, he thought he'd try to write one of his own. So far, it's working out far better than he expected. Mike currently lives in the Los Angeles area. He's an avid traveler and beer aficionado, and since nobody has told him to stop yet, he continues to write fiction.. His latest novel is MJ-12: Endgame.

I’m extraordinarily pleased to be doing another mind meld and I hope this feature finds a permanent home soon. I’m less pleased about having to actually choose my favorite among the Hugo Award winners for Best Novel. It’s honestly not fair. Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War? The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula Le Guin? Dan Simmons’ Hyperion? I mean, Neuromancer is on this list! We got several Connie Willis books, some Kim Stanley Robinson novels, we got Neil Gaiman, Ann Leckie’s awesome Ancillary Justice, John Scalzi’s too-much-fun Redshirts and N.K. Jemisin’s brilliant landmark Broken Earth trilogy in a historic three-peat. I almost went with Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrel by Susanna Clarke, which remains one of my favorite books and was a true pleasure to read. But if I’m truly honest, I need to go with Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policeman’s Union.

Right? I know. I’m the last guy to get all literary, believe me. I’m not necessarily a fan of Chabon’s other works. But this book in particular stuck with me, made me think, opened some doors in my head and is a tiny bit to blame for my own career. I’d had an interest in alternate history and historical fantasy works for years, going back to The Guns of the South by the iconic and amazing Harry Turtledove, as well as Fatherland by Robert Harris. I liked the intellectual exercise of plotting history based on changes to these wonderful inflection points. They planted the seeds that would bloom in my brain years and years later and lead me down a similar road. Chabon did all this, of course, in developing the community of Sitka, Alaska, turning that sleepy little town into a bustling haven for the Jewish people during and after World War II. He imagined a very divergent post-war society with all kinds of cool details only alluded to in the book. But what he did so well, and what truly captured my imagination, was not his political alternatives, but his cultural ones. Here, he took Jewish culture and used his setting details to truly make it a living, breathing thing, divergent and strange but yet recognizable and comfortable all the same. And he populated the story with truly memorable characters and a resonant story. All of this combined to make Chabon’s alternate history truly immersive. In some alt-histories, I find myself still comparing the divergences in history as the story moves forward. But in The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, I surrendered completely and utterly to the story. The brilliant setting was yet another character, permeating the narrative perfectly.

Did I have more fun reading Strange and Norrell and Redshirts? You betcha. But Chabon was perhaps the most brilliant example of the kind of alternate history that I aspired to write years later.

Nebula-nominated Beth Cato is the author of the Clockwork Dagger duology and the Blood of Earth trilogy from Harper Voyager. She’s a Hanford, California native transplanted to the Arizona desert, where she lives with her husband, son, and requisite cats. Follow her at BethCato.com and on Twitter at @BethCato.

Paladin of Souls by Lois McMaster Bujold. What makes it stand out among so many excellent Hugo winners? First of all, it's the second book in a series, following up the excellent Curse of Chalion. As much as I loved that book, however, Paladin resounded even more for me because of its heroine, Ista. She's an older woman who has lost her husband and child. Other people underestimate her, assuming her to be fragile and insane after all she has endured. Ista is a woman who wants to escape and truly live again, and as someone with major anxiety and depression, wow, can I relate. This is one of those books that I wished would never end. Fortunately, there ARE more books in this setting; in particular, the Penric novellas are cozy and wonderful, and I am woefully behind in reading the rest of them. I should correct that. Thank you for reminding me to do so, Mind Meld.

Marguerite Kenner is a native Californian who has forsaken sunny paradise to live and work with her partner, Alasdair Stuart, in a UK city named after her favorite pastime but pronounced differently. She manages her time between co-owning Escape Artists, editing its YA imprint Cast of Wonders, lecturing, grappling with legal conundrums as a lawyer, studying popular culture (i.e. going to movies and playing video games), and curling up with really good books. You can follow her adventures on Twitter.

My favorite best novel Hugo winner is from 1982 -- 'Downbelow Station' by C. J. Cherryh. I still own my first copy of it, a dog-eared, well-loved paperback. Captain Signy Mallory was the first 'unlikable woman' protagonist I remember resonating with, and I think I still know all the words to the filk song...

Sara Megibow is a literary agent with kt literary out of Highlands Ranch, CO. She has worked in publishing since 2006 and represents New York Times bestsellers authors including Margaret Rogerson, Roni Loren, Jason M. Hough and Jaleigh Johnson.

Bacigalupi described imagining the concept and creating THE WINDUP GIRL from there. Listening to him speak about his work helped me appreciate the nuances and conflicts in his book even more. Cons can be expensive but if it’s in the budget they are an amazing experience! THE WINDUP GIRL sits on a place of honor on my bookshelf because meeting the author in person after already having fallen in love with his book was such a wonderful experience.

Jaime Lee Moyer is a writer of fantasy and science fiction, herder of cats, occasional poet, and maker of tangible things. Her first novel, Delia's Shadow, was published by Tor Books, and won the 2009 Literary Award for Fiction, administrated by Thurber House and funded by the Columbus Arts

Council. Two sequels, A Barricade In Hell and Against A Brightening Sky, were also published by Tor. Her new novel, Brightfall, came out from Jo Fletcher Books on September 5, 2019.

In 1979, Vonda McIntyre’s novel, Dreamsnake, won the Hugo for best novel. I didn’t discover the novel until years later, one of the few books I hadn’t read in the paperback rack at the library. The three racks full of paperbacks were a constantly changing treasure chest of SFF books, and Dreamsnake was definitely a treasure. I remember falling in love from the first word. The protagonist of this novel is Snake, a young healer who relies on her three snakes, Grass, Mist, and Sand, to heal the people who seek her out. Grass is her dreamsnake, rare and precious and hard to come by. When a desert tribe asks her to heal a very sick little boy, Snake knows these people are afraid of her, and afraid of her snakes. What she doesn’t realize is how deep that fear runs and what it will cost her. Snake blames herself. McIntyre painted a vivid picture throughout Snake’s travels of what it means to be different and other, to be needed and feared at the same time, and did so in a way that felt emotionally true. I saw so many parallels to the real world. Great characters, and excellent worldbuilding, suck me into a book every time. This book made a lasting impression on me. Not only is Dreamsnake my favorite Hugo winner, it’s in my top ten list of all-time favorite novels.

POSTED BY: Paul Weimer. Ubiquitous in Shadow, but I’m just this guy, you know? @princejvstin.