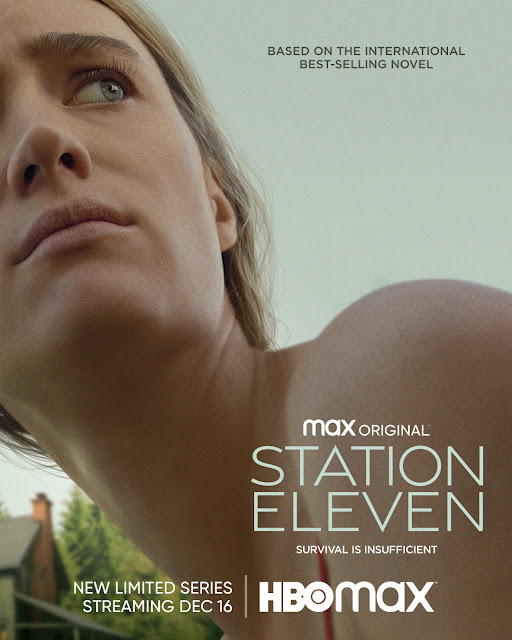

You'd think lethal virus stories are in bad taste these days, but Station Eleven is the triumphant cathartic release we didn't know we needed

Station Eleven, the miniseries adaptation of the 2014 novel by Emily St. John Mandel, follows the lives of a handful of survivors of a global pandemic that ended civilization. That sounds exactly like the last thing we'd want to see on TV during a real global pandemic that might, perhaps, really end civilization. But what this story has to offer is completely different from your standard post-apocalyptic drama. Except for news reports in the background of a scene, we don't see the masses out of control, fighting over scraps and forming unstable factions, or the desperate horror of watching passersby drop like flies. The incalculable toll of death is implied.

What this story is interested in showing is how life persists after so much death. Showrunner Patrick Somerville famously pitched the series as “a postapocalyptic show about joy.” We follow Kirsten, a young actress randomly paired with a stranger who shelters her during the first weeks of the pandemic, and whose sudden brush with tragedy makes her so hypervigilant that she casually carries a knife with her at all times. We follow Clark, a gentle but bitter middle-aged man who ends up leading a community of survivors permanently stranded at an airport, and whose unlikely ascent to power eventually changes him from conservator to conservative. We follow Tyler, a neglected child of self-absorbed parents, whose repeated experiences of rejection and mistreatment mold him into an emotionally stunted manchild with a vendetta against the past. What connects their journeys is how they were touched by the death of narcissist womanizer and movie star Arthur, as well as the graphic novel Station Eleven, self-published by Arthur's ex-wife Miranda. In particular, the twin trajectories of Kirsten and Tyler will be shaped by their drastically differing readings of the same text.

You don't need the backdrop of a lethal pandemic to tell a story about the power of stories. In fact, Mandel's original intention wasn't even to write a novel about the end of the world; she just liked the image of wandering actors bringing joy to village after village. You may as well remove the whole pandemic plot from Station Eleven and see it for what lies at its core: the double-edged power of performance. Both Kirsten and Tyler have been deeply moved by a story, and both will reenact it at key moments of their lives. However, Kirsten uses performance as a balm (at one point a spectator remarks that the troupe of actors brought "new life" to their town), while Tyler uses performance as a weapon. As for Clark, his fear of things decaying makes him keep them stuck in place, where he continues to tell stories about them but doesn't let the story around them move forward.

To explore this theme it doesn't really matter that the plot happens in a setting where almost everyone is dead, because those who are left alive still face the same old question of how to live. What should we do about the things that time takes from us? Make beauty from them, like Kirsten? Lock them inside a display case, like Clark? Or burn them, like Tyler? This is not a story about finding meaning after the apocalypse; it's a story about finding meaning, period. The trappings of world-ending catastrophe are only there to enhance the emotional content, to make the implicit explicit.

This is why it doesn't feel distracting when the plot of Station Eleven jumps between time periods. The path of things from A to B can find more useful routes than a straight line. It doesn't feel like a different world when we see the scenes before the mass death. It's all the same story. It's always the same story. That the world has ended does not change the fundamental questions of life.

However, the path of things from novel to TV series did meet with some bumps. The character of Tyler is made much more ambiguous in the adaptation, but without the benefit of added nuance. Whereas he was unmistakably a monster in the novel, here he is given a tentative chance of redemption. This defuses the tension that sustained the story before it's given a proper answer. Once Kirsten and Tyler realize that their lives have been shaped by their love for the same book, the main conflict of the series becomes about which relationship to art (and which relationship to the dear deceased Art) will prevail. Kirsten takes a page from Hamlet and orchestrates a session of psychodrama where Tyler's moment of growth is to achieve the basic human decency of not slitting Clark's throat. In a way, this fits with their characterizations: once again, Kirsten gets to use performance to heal things, Tyler uses it to break things, while Clark stands still and describes the way things were. That works; that's who they are. However, in proportion to the significance of the conflict, it's rather anticlimactic. We spent plenty of time following Miranda's determination to preserve her artistic integrity and create her masterpiece, the only part of her that survives the death of all things, and the way in which the rival interpretations of her work are left not-quite-resolved leaves a deflated feel.

The actual resolution comes later, when Kirsten reunites with her old friend and rescuer Jeevan, and he says he's happy that his family will get to meet her in person, because for years all they've known of her are his stories, and this time they'll see the real her.

In this beautifully shot, movingly acted, sharply written, captivatingly edited, epically scored version of Station Eleven, that is the final victory over oblivion: the moment when a story comes alive.

The Math

Baseline Assessment: 9/10.

Bonuses:

+1 for Dan Romer's soundtrack, +1 for the power duo of Hiro Murai and Christian Sprenger, who together bring a flawless sense for shot composition.

Penalties:

−3 for watering down Tyler's villainy.

Nerd Coefficient: 8/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.