Anyway, on with the stories:

... and other disasters by Malka Older

Malka Older's first short fiction collection is a chapbook-length affair from Mason Jar Press, bringing together both fiction and poetry into one beautifully curated package. Older's work particularly appeals to me because we're in not-dissimilar careers, so she brings a lot of experience to her fiction that I recognising and find illuminating. This came through strongest for me in stories which lay bare the expectations and power dynamics which travellers to other cultures bring with them - "The Rupture", about a young woman coming to study on a dying earth despite the protestations of her family about how dangerous it is, and "Tear Tracks", about the first diplomatic visit to an alien culture and one traveller's attempt to match up her communication, her perceived role and the very different situation in which she finds herself. Both are stories which, despite living in the perspective of their transient visitor protagonists (and maintaining sympathy for them), avoid othering the cultures being visited, and the result is something beautiful. There are a couple of more on-the-nose political explorations here too, including "The Divided," a story in which the USA literally becomes surrounded by an impenetrable barrier and the impact it has on those left outside, and "The End of the Incarnation", a piece whose parts are scattered through the rest of the collection and chronicle the break-up of the United States and speculate on what might come next.

What I found challenging about the stories in this collection are the lack of recognisable endings to most stories; most of the time, the focus on putting forward an experience for a set of protagonists rather than delivering a neatly-wrapped storytelling experience. On a craft level its an understandable choice for the kinds of narratives these are, and I appreciate the resistance to easy story beats and the nuance this adds to the scenarios in many of the stories. Unfortunately, when put together in a collection where this keeps happening, the frustration does linger from piece to piece, and I suspect I'd have had a better time if I'd broken up my reading of individual stories with other writing styles. Regardless, ...and other disasters is a great achievement, and well worth picking up for anyone interested in Older's writing.

Rating: 8/10

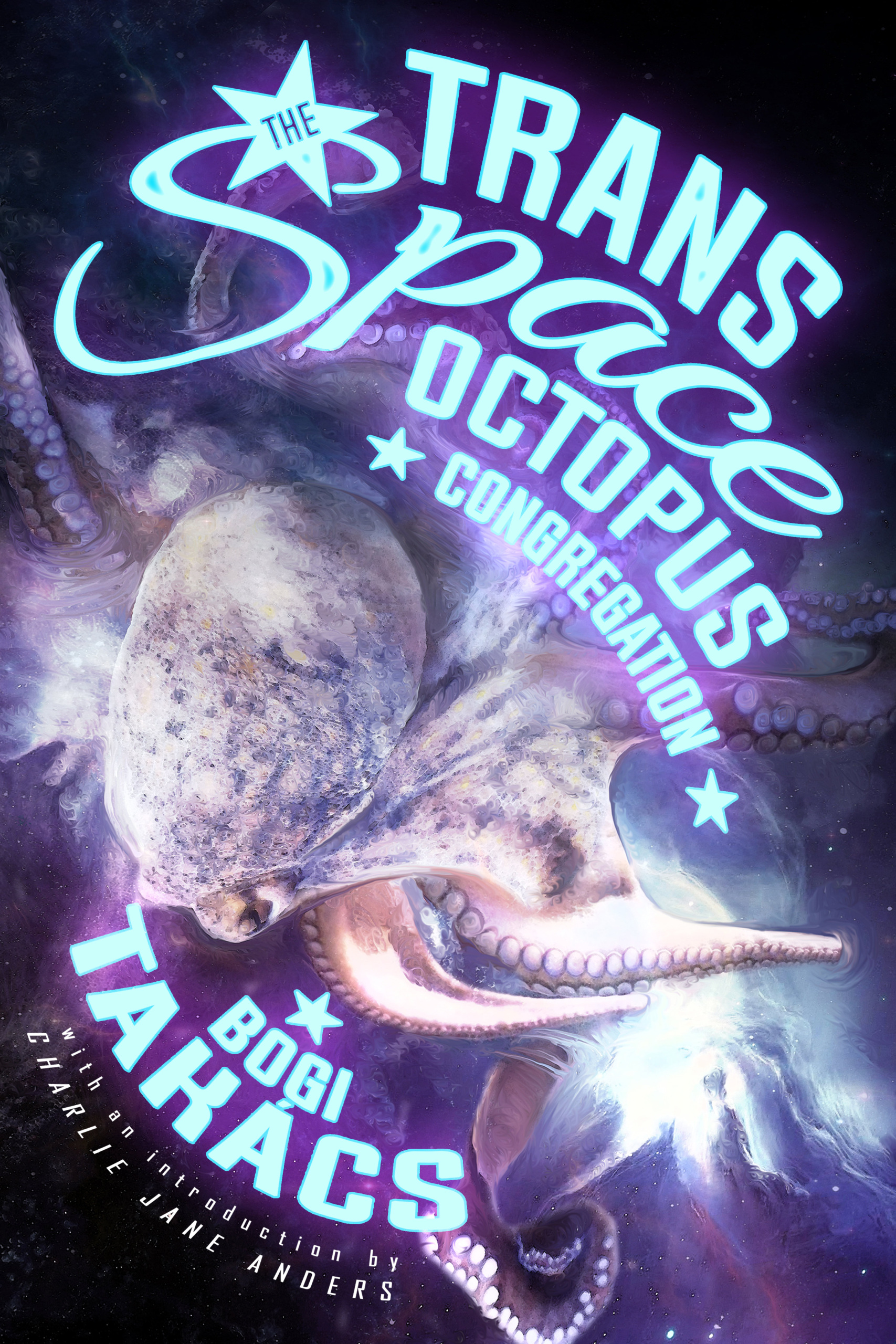

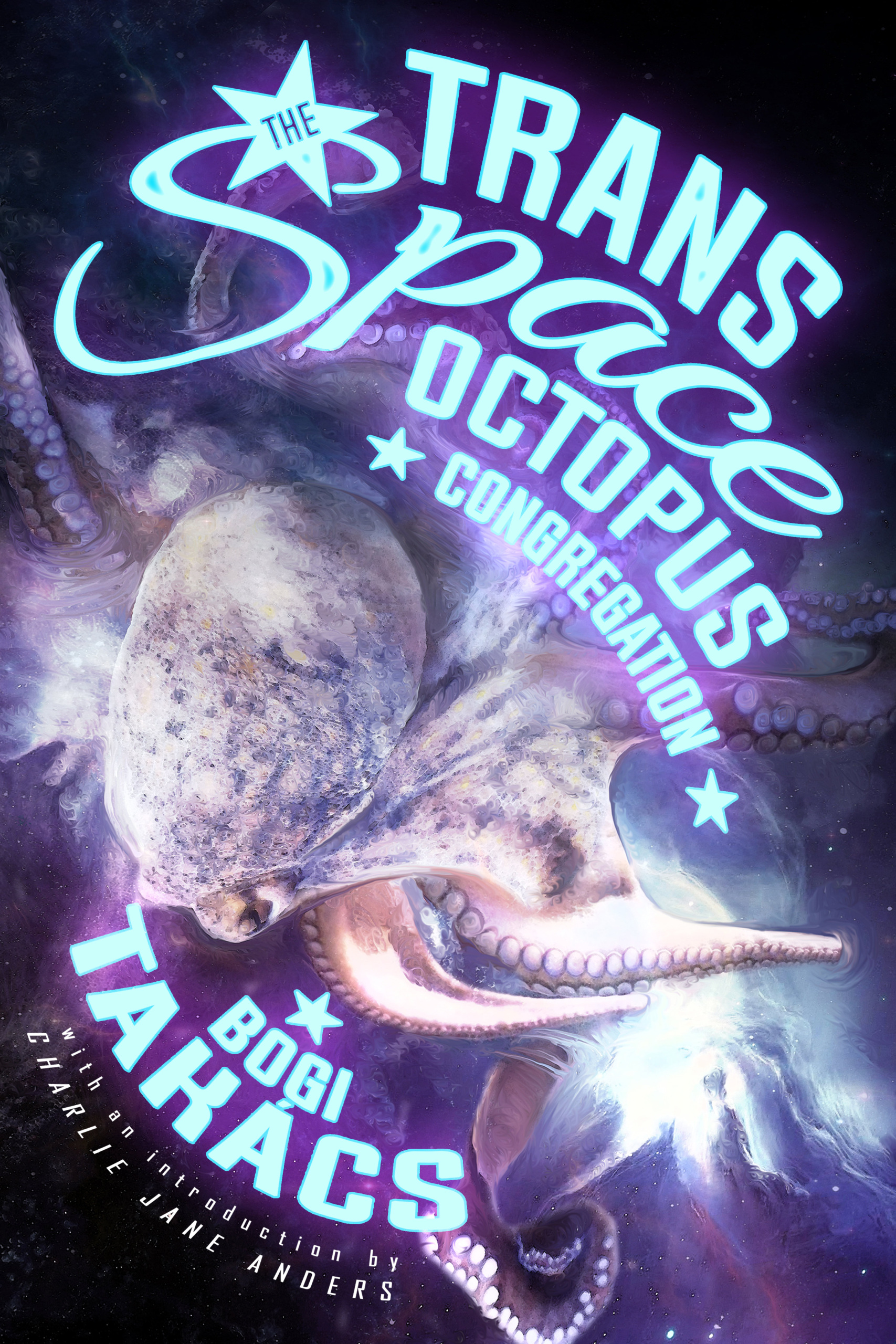

The Trans Space Octopus Congregation by Bogi Takács

Let's get the obvious out of the way first: titles don't come much better than this. Takács' debut short fiction collection (I believe e has also released a poetry collection this year) is the very best kind of "does what it says on the tin": the kind where the tin has an exquisite purple octopus on the front and the word "space" in a cursive font and queerness front and centre in the title. Its a cover holding a dense and varied set of stories, ranging from near-future slice of life to magical space speculation, all wound through with some fascinating thematic resonance and centring characters whose nuanced identities require no explanation or excuse, regardless of whether the characters experience marginalisation in their own contexts (and often they do). Themes of marginalisation and difference in all their forms are ever present, whether they are front and centre of the narrative or just another consideration for characters to work in, and there's a nuanced treatment of how characters communicate across experiential divides, usually handled with sympathy though not always with success, that makes for some great interpersonal arcs packed into the small packages here.

Another theme that jumped out of me while reading was the many stories that deal with how people maintain community and tradition: whether it be the octopus protagonists of "Some Remarks on the Reproductive Strategy of the Common Octopus" or "A Superordinate Set of Principles", the deeply affecting refugee/alien invasion story of "Given Sufficient Desperation", or the many stories centring Jewish communities (spacefaring and otherwise). Takács makes an art form of offering up windows into worlds which don't feel the need to overexplain or overcomplicate their specific, nuanced traditions, while still ensuring that everything feels deliberate and well-placed within the story contexts. Particularly in more overtly science fictional stories, it feels like there's a deliberate rejection of the dichotomy between the behaviour of "rational" human behaviour and the traditions of myth, belief and ritual which often get left at the door as soon as there's a spaceship involved. It helps that the prose is so consistently beautiful, offering an otherworldly quality even to more straightforward tales. I came out of The Trans Space Octopus Congregation feeling like in many ways I'd only skated the surface of what Takács had to show me in this collection, and I'm keen to see what e comes out with next.

Rating: 9/10

Beneath Ceaseless Skies (284, 287)

Let's get the obvious out of the way first: titles don't come much better than this. Takács' debut short fiction collection (I believe e has also released a poetry collection this year) is the very best kind of "does what it says on the tin": the kind where the tin has an exquisite purple octopus on the front and the word "space" in a cursive font and queerness front and centre in the title. Its a cover holding a dense and varied set of stories, ranging from near-future slice of life to magical space speculation, all wound through with some fascinating thematic resonance and centring characters whose nuanced identities require no explanation or excuse, regardless of whether the characters experience marginalisation in their own contexts (and often they do). Themes of marginalisation and difference in all their forms are ever present, whether they are front and centre of the narrative or just another consideration for characters to work in, and there's a nuanced treatment of how characters communicate across experiential divides, usually handled with sympathy though not always with success, that makes for some great interpersonal arcs packed into the small packages here.

Another theme that jumped out of me while reading was the many stories that deal with how people maintain community and tradition: whether it be the octopus protagonists of "Some Remarks on the Reproductive Strategy of the Common Octopus" or "A Superordinate Set of Principles", the deeply affecting refugee/alien invasion story of "Given Sufficient Desperation", or the many stories centring Jewish communities (spacefaring and otherwise). Takács makes an art form of offering up windows into worlds which don't feel the need to overexplain or overcomplicate their specific, nuanced traditions, while still ensuring that everything feels deliberate and well-placed within the story contexts. Particularly in more overtly science fictional stories, it feels like there's a deliberate rejection of the dichotomy between the behaviour of "rational" human behaviour and the traditions of myth, belief and ritual which often get left at the door as soon as there's a spaceship involved. It helps that the prose is so consistently beautiful, offering an otherworldly quality even to more straightforward tales. I came out of The Trans Space Octopus Congregation feeling like in many ways I'd only skated the surface of what Takács had to show me in this collection, and I'm keen to see what e comes out with next.

Rating: 9/10

Beneath Ceaseless Skies (284, 287)

Beneath Ceaseless' Skies "two stories every two weeks" format has been posing an unfortunate challenge to my particular review capacity - individual issues feel like there isn't enough to talk about, but by the time I reach critical mass I've forgotten what stories are in which issues, and probably fallen behind on individual issues as well. A couple of issues have stood out over the past couple of months, though, hence the slightly eclectic issue selection in this roundup.

Issue 284 brings together a pair of stories which work beautifully together: both are tales told through an academic lens of dubious interpretive value, dealing with narratives within narratives and the unreliability of mirrors. If those feel like quite specific similarities, what's even more impressive is how different each story feels within those constraints: "The Mirror Dialogues" by Jason S. Ridler is a series of fragments which cover the relationship between a "mirror scribe" and their sovereign, and the way the relationship between the two shapes the world around them. It's a story which keeps the reader guessing as to what's real and what's really going on, and the academic lens really allows that uncertainty to shine, letting us look back at a fictional history as uncertain as our own and to make our own judgements about the external interpretation and the events themselves. In contrast, M.E. Bronstein's "Elegy of a Lanthornist" offers up the story, in her own words, of Isabel Hayes-Reyna, a scholar herself who is recognised for a groundbreaking interpretation of an earlier text, whose dark magical elements she herself starts to experience, with grim and apparently tragic consequences. Of course, because we are engaged as readers of fantasy, we are far more inclined to take Isabel's path of discovery seriously than her contemporaries, whose dismissive and pitying attitudes towards her apparent disappearance come across more as condescending than as an interpretation to be taken equally seriously. An impressive pair made stronger by the pairing.

Of equal note is the double Issue 287, with four original stories - all quite long - for our reading pleasure. We start off with a darkly humorous entry from K.J. Parker, "Portrait of the Artist", about a young woman who has discovered a rather unpleasant way to try and raise the capital for an investment that should bring her feckless family out of (relative) destitution. Its a story whose protagonist is deeply engaging despite not exactly being sympathetic, and the recurring motif on the value of money - and other things - is darkly entertaining and also plays with our sympathies in interesting ways. The issue follows that up with "Sankalpa", a time-skipping reincarnation story from Marie Brennan, drawing on Indian myth to tell the story of a woman engineering a revenge that's lifetimes and huge wars in the making.

"One Found in a World of the Lost" weaves together the story of two very different twins, Pavitra and Gayatri, living in a community increasingly struggling to survive against the will of the ground they live on. When Gayatri, the far better hunter of the two, is killed unexpectedly, Pavitra has to deal with her loss and with her own feelings of self-worth and the skills she feels she lacks in comparison to her sister. Its a story that deals well with self-worth and coming into one's own in an intriguing setting. Finally, there's "The Witch of the Will" by Aaron Perry, about a witch who, having removed free will from a King, is asked to do the same thing by a young man who then forces her to deal with the consequences of his predictable actions. It's a story whose lighthearted, matter-of-fact tone hides a really dark core, and it packs a hefty punch into the decades of events it covers in its short length.

Rating: 8/10 for both of these standout issues.

The Dark, Issue 52

Three quarters of the stories in this issue of The Dark deal with women looking, in some way, for better lives, but that's basically the only thing they have in common. In "Brigid Was Hung By Her Hair From the Second Story Window" (original), Gillian Daniels tells the story of an immigrant from Ireland to Boston, who accepts an offer of marriage from the man who brought her over as a maid, only to have to give things up for a magical escape when his abuse becomes too much. She's given a second chance in the form of a better second marriage, but the feeling that there will be a reckoning for the "magic" which enabled her escape is borne out in a twisted way in the story's final words. The title is a great stylistic choice here, drawing attention to a turning point that otherwise could feel matter-of-fact in the everyday abuse of Brigid's first marriage, and underscoring her lack of agency and draws attention to the lengths she feels she has to go to in order to have even the most basic choices about her life. The issue's second story, "Our Town's Talent" (reprint), is told from the nameless collective perspective of a traditional modern town's wives, on the occasion of their childrens' school's annual talent show. After all the effort which goes into preparing their children to showcase their talents, a newcomer to the town rocks the boat by holding a show of her own in which a winner will be chosen, and upsets the balance of the town in a way that's unexpected and yet wholly fitting for a tale of this kind. Its a story which ends up being about agency, challenging our assumptions about the value of the undifferentiated feminine chorus at its heart and their complicity in their own mundane oppression. The result is something that, while not exactly uplifting, offers a form of escape that I found surprisingly satisfying.

Providing the second original story in this issue is Ruoxi Chen, with "The Price of Knives": a Chinese take on the Little Mermaid that ties elements of the myth to the historical practice of foot-binding. Its a story that could end badly for its mermaid protagonist, who makes a choice between giving up her voice or the sensation of walking on knives as the "price" for transformation (she chooses the price of song), only to discover a society on land that she has no chance of fitting in to, with a Prince whose professed affection for her ends up being as hollow as we'd expect. When foot binding takes away her autonomy and ability to walk, the mermaid finds an escape that will allow her to regain what she's lost, at a price that this time she's very willing to pay. Like "Our Town's Talent", the voice of the collective which tells this story is a great device, this time adding to the growing threat as we wonder who the second-person narrative, with all its asides about what the listener already knows, is aimed towards. Rounding out this month's offering is “All My Relations” by Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada (reprint), an own voices Hawai'ian story about how annoying disrespectful divers with cameras can be. I mean, no, it's not really about that, but I definitely relate to the "monster" here for that and many other reasons, and its a brilliant, dark story with teeth that made me add the anthology series its drawn from onto my Christmas list for this year.

Rating: 7/10

Clarkesworld Issues 155 and 156

I've had back issues of Clarkesworld piling up for the past few months as well, and in making the effort to catch up I read through August and September in quick succession. August turned out to be a great point at which to pick things back up, with some stories that run the gamut from fun slice-of-life (Harry Turtledove's scenes from an alternate-ice-age-Yorkshire vet employing an ingenious solution to a local mammoth's broken tusk) to heartbreaking human moments (Rachel Swirsky's "Your Face", about a mother visiting a "backup" of her daughter several years after her death). The story that took me most by surprise was Chen Qiufan's "In this Moment, We Are Happy", translated (seamlessly) by Rachel Kuang, which takes the form of a three-part documentary script on childbirth and technology over a period of decades. It's a surprisingly evocative format, and I found I could really follow along with not just the narratives themselves, but the descriptions of videography used in different scenes, the way things were cut together, all adding up to something that felt really tangible as the "intended" medium as well as the medium we actually have. In the three parts of the documentary, Chen weaves together a surrogate mother and a parent-to-be seeking to use a surrogate; followed by a man who has become pregnant for an artistic stunt and a same-sex female couple giving birth using only their genetic material; and finally a far-future fertility cult which is apparently developing a controversial transhumanist approach to a further-future reproductive crisis. Its all handled in a way that's deeply sympathetic to all of the characters, normalising queerness and offering agency and respect to characters from marginalised identities; even the male artist, whose motives are interrogated as selfish and bizarre, is offered a humanising arc, although it's the bluntest tool in a generally quite subtle toolbox. As is often the case in documentaries, there's no answers or single narrative line here - just windows into the lives of people whose different experience add up to something which resonates on a broader level. I found myself tearing up at the end of this story, having felt that I really had watched a window into these different peoples' lives through a camera lens.

Compared to August, September was slightly more subdued, although there's still some fun stuff here. "Dave's Head", by Suzanne Palmer, features a road trip with the titular object, who also happens to be a sentient animatronic dinosaur from an abandoned theme park. The story itself is just as weird and wonderful and surprisingly poignant as that sounds. I also greatly enjoyed the long novelette "To Catch All Sorts of Flying Things" by M.L. Clark, a mystery about interspecies cooperation and rights to life on a planet colonised by multiple species with more to it than initially meets the eye. While I struggle to keep up with Clarkesworld, and not all of their stories hit the spot for me, there's still a lot to enjoy in the kind of meaty short-form science fiction they publish, and the continued commitment to translated works is also a huge bonus.

Rating: 8/10 for August, 7/10 for September

POSTED BY: Adri Joy, Nerds of a Feather Co-editor, is a semi-aquatic migratory mammal most often found in the UK. She has many opinions about SFF books, and is also partial to gaming, baking, interacting with dogs, and Asian-style karaoke. Find her on Twitter at @adrijjy.