Content warning: discussion of rape in classical mythology

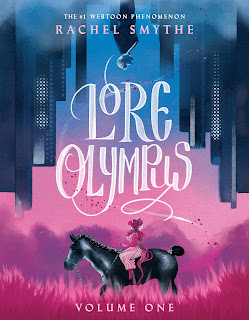

The first thing I noticed about Lore Olympus, and why I bought it, is that it is an incredibly pretty book. Rachel Smythe chooses a strikingly simple art style, with strong, bold colours for each character, and flat backgrounds to highlight them, with a lot of white space on the page to focus on the central images. There’s very little in the way of extraneous environmental art – you just get what you need for the plot and the atmosphere, well spaced-out on the page and often laid out using that white space to highlight the movement of the narrative. This means that although the physical book is 384 pages, it’s actually an extremely pacey read, and you get a sense of what’s happening, what the feeling of each page is, before you even get to processing the pictures and words. On the one hand, it’s a very communicative way of doing things, allowing you to get really immersed in the storytelling, but on the other, it massively exacerbates the problem that graphic novels can often have, of being such quick reads that they don’t feel good value for money, when you think purely of the time you spend with them. In some, the art style forces you to slow down, to appreciate all the little nuances (I personally find Christian Ward’s art style excellent for this), but in Lore Olympus, the pared-down, simple visuals are something of a double-edged sword, and it was extremely difficult to pace myself reading it, however much I liked them aesthetically.

|

| Smyth's pages are incredibly dynamic |

The first thing I noticed about Lore Olympus, and why I bought it, is that it is an incredibly pretty book. Rachel Smythe chooses a strikingly simple art style, with strong, bold colours for each character, and flat backgrounds to highlight them, with a lot of white space on the page to focus on the central images. There’s very little in the way of extraneous environmental art – you just get what you need for the plot and the atmosphere, well spaced-out on the page and often laid out using that white space to highlight the movement of the narrative. This means that although the physical book is 384 pages, it’s actually an extremely pacey read, and you get a sense of what’s happening, what the feeling of each page is, before you even get to processing the pictures and words. On the one hand, it’s a very communicative way of doing things, allowing you to get really immersed in the storytelling, but on the other, it massively exacerbates the problem that graphic novels can often have, of being such quick reads that they don’t feel good value for money, when you think purely of the time you spend with them. In some, the art style forces you to slow down, to appreciate all the little nuances (I personally find Christian Ward’s art style excellent for this), but in Lore Olympus, the pared-down, simple visuals are something of a double-edged sword, and it was extremely difficult to pace myself reading it, however much I liked them aesthetically.

It didn’t help that the story as it presents itself is also pretty damn readable. The characters are very immediate, and show themselves vividly almost as soon as they appear on the page. And the two protagonists are incredibly likeable dorks, amid a world of glamour, which is always appealing to me personally. Smythe does a great job of this – creating personable characters in a quick and smooth way, so you can get into the feel of who they are at a pace that feels matched to the speed of the narrative. I was invested, from page one, in them as people.

However, once you get past the loveliness of the art and the book as an object (the cover is also, frankly, gorgeous), and the loveliness of the characters as they are presented to you, there is a glaring problem that does need to be addressed.

There has always been a market for retellings of Greek myths, but they seem to be particularly in vogue at the moment, both within SFF and in the wider literary sphere (from Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, to graphic novels like Kieron Gillen’s The Wicked + The Divine). And one of the flavours that seems to be particularly prominent is retellings of the Hades and Persephone myth. The much acclaimed (and in my opinion fantastic) game Hades weaves it into its narrative, and both Lore Olympus and Linda Sejic’s Punderworld published their first physical volumes in 2021, likewise taking this myth as their focus. And what a lot of these particular modern retellings have in common is a decision to rewrite the relationship between Hades and Persephone into a mutual romance.

If you’re not familiar with the original myth, “romance” is not the word most people would use when describing it. In the title of most translations and direct scholarly works, the word “rape” is used in its traditional sense of “stealing women away by force”, with a strong implication of its modern usage underlying it.

To be clear, the original myth is about as casually violent in its treatment of women as Greek mythology gets. It is a story of a young woman on the cusp of adulthood suddenly grabbed and stolen away by an older man, a relative (though how close depends on which version of their family tree you want to use), through a hole in the ground, and trapped with him in the underworld while her mother Demeter weeps, not knowing where her daughter has gone, and in her grief and rage inflicts a ravaging winter upon the world. Eventually, she discovers where her daughter is, and wants her back, but by trickery, Hades manages to ensure that Persephone cannot leave his domain permanently, and so they agree that she will spend half of her year back home with her mother, and half with her new “husband” in the underworld. It’s a myth in which not one but two women’s happiness and lives are upended because a man – albeit a god – wants something he shouldn’t have, and so takes it by force.

And so I find it particularly troubling when this myth is rewritten to make that violent act into something good and beautiful.

In Lore Olympus, Persephone is the sheltered daughter of a helicopter parent who has trapped and hidden her only child away from all society, and finally allowed her out simply because it was into the care of a sworn virgin (Artemis) to look after her while she attends university to follow that same, chaste path. Demeter is an unseen shadow in the background of Persephone’s life for much of the book, only visible in flashbacks, affecting her actions and choices but without showing up on the page, but unambiguously portrayed as a problem at best. Hades, meanwhile, is an introverted and slightly awkward part of the high society of Olympus, who likes Persephone on sight but is too shy to act upon that attraction until various events leave her in his care while drunk. He is the perfect gentleman throughout their encounters, and we see both of them thinking about the other, but convinced there’s no chance of a mutual interest.

Hades is specifically contrasted in this portrayal at several points with Zeus, whose own behaviour is (mildly) decried, and yet that behaviour is exactly equivalent to Hades’ own in the original myth. Likewise, at one point in the story, a character is sexually assaulted in a way that parallels some parts of Persephone’s myth. It is portrayed as the traumatic act it is, and the perpetrator as a villain for it.

And yet that core part of the myth is disregarded, and we are shown the beginnings of a delicate, fragile romance that might, just might, allow a sheltered girl to escape the clutches of her overbearing mother. It’s not only discarding the original myth, but directly inverting it, making someone who ought to be the villain, a rapist and a kidnapper, into a delicate, gentle love interest playing a part in “liberating” Persephone from her previous life, while at the same time shifting her grieving mother into a more antagonistic role.

Now, I don’t think the story needs to be accurate to the original myth – many of the best retellings very much are not – but it seems a particularly problematic instance here, and as a trend in general, to rewrite a rapist (I’m going to keep saying it because it’s true) into a hero, a liberator, a lover and a friend. In the wake of so many good reinterpretations, ones that seize upon forgotten, overlooked or victimised characters and give them their own voices, it seems a really awful choice to decide to champion instead someone who we are now in a position to be able to critique more openly, in a way that much reception of the myth – written, as it was, by men in patriarchal structures – has never grappled with. We exist in a time where we really can dismantle those stories, and lay bare the truth of them… so why instead choose not only to go along with them, but to help them along, to continue that cycle?

Lore Olympus itself is not responsible for the entire trend. It cannot, of course, be blamed for all these stories existing in the current narrative. But Smythe did take a rapist character and rewrite him into a sweet, kind love interest, and I think even aside from being part of a really unpleasant general trend, this decision at the core of the story permeates outwards and taints everything else. Yes, the art is beautiful, the layouts clever, the storytelling pacy and the characters engaging… but it’s not enough, nor should it be, to get past the problem at the core.

The Math

However, once you get past the loveliness of the art and the book as an object (the cover is also, frankly, gorgeous), and the loveliness of the characters as they are presented to you, there is a glaring problem that does need to be addressed.

There has always been a market for retellings of Greek myths, but they seem to be particularly in vogue at the moment, both within SFF and in the wider literary sphere (from Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, to graphic novels like Kieron Gillen’s The Wicked + The Divine). And one of the flavours that seems to be particularly prominent is retellings of the Hades and Persephone myth. The much acclaimed (and in my opinion fantastic) game Hades weaves it into its narrative, and both Lore Olympus and Linda Sejic’s Punderworld published their first physical volumes in 2021, likewise taking this myth as their focus. And what a lot of these particular modern retellings have in common is a decision to rewrite the relationship between Hades and Persephone into a mutual romance.

If you’re not familiar with the original myth, “romance” is not the word most people would use when describing it. In the title of most translations and direct scholarly works, the word “rape” is used in its traditional sense of “stealing women away by force”, with a strong implication of its modern usage underlying it.

To be clear, the original myth is about as casually violent in its treatment of women as Greek mythology gets. It is a story of a young woman on the cusp of adulthood suddenly grabbed and stolen away by an older man, a relative (though how close depends on which version of their family tree you want to use), through a hole in the ground, and trapped with him in the underworld while her mother Demeter weeps, not knowing where her daughter has gone, and in her grief and rage inflicts a ravaging winter upon the world. Eventually, she discovers where her daughter is, and wants her back, but by trickery, Hades manages to ensure that Persephone cannot leave his domain permanently, and so they agree that she will spend half of her year back home with her mother, and half with her new “husband” in the underworld. It’s a myth in which not one but two women’s happiness and lives are upended because a man – albeit a god – wants something he shouldn’t have, and so takes it by force.

And so I find it particularly troubling when this myth is rewritten to make that violent act into something good and beautiful.

In Lore Olympus, Persephone is the sheltered daughter of a helicopter parent who has trapped and hidden her only child away from all society, and finally allowed her out simply because it was into the care of a sworn virgin (Artemis) to look after her while she attends university to follow that same, chaste path. Demeter is an unseen shadow in the background of Persephone’s life for much of the book, only visible in flashbacks, affecting her actions and choices but without showing up on the page, but unambiguously portrayed as a problem at best. Hades, meanwhile, is an introverted and slightly awkward part of the high society of Olympus, who likes Persephone on sight but is too shy to act upon that attraction until various events leave her in his care while drunk. He is the perfect gentleman throughout their encounters, and we see both of them thinking about the other, but convinced there’s no chance of a mutual interest.

Hades is specifically contrasted in this portrayal at several points with Zeus, whose own behaviour is (mildly) decried, and yet that behaviour is exactly equivalent to Hades’ own in the original myth. Likewise, at one point in the story, a character is sexually assaulted in a way that parallels some parts of Persephone’s myth. It is portrayed as the traumatic act it is, and the perpetrator as a villain for it.

And yet that core part of the myth is disregarded, and we are shown the beginnings of a delicate, fragile romance that might, just might, allow a sheltered girl to escape the clutches of her overbearing mother. It’s not only discarding the original myth, but directly inverting it, making someone who ought to be the villain, a rapist and a kidnapper, into a delicate, gentle love interest playing a part in “liberating” Persephone from her previous life, while at the same time shifting her grieving mother into a more antagonistic role.

Now, I don’t think the story needs to be accurate to the original myth – many of the best retellings very much are not – but it seems a particularly problematic instance here, and as a trend in general, to rewrite a rapist (I’m going to keep saying it because it’s true) into a hero, a liberator, a lover and a friend. In the wake of so many good reinterpretations, ones that seize upon forgotten, overlooked or victimised characters and give them their own voices, it seems a really awful choice to decide to champion instead someone who we are now in a position to be able to critique more openly, in a way that much reception of the myth – written, as it was, by men in patriarchal structures – has never grappled with. We exist in a time where we really can dismantle those stories, and lay bare the truth of them… so why instead choose not only to go along with them, but to help them along, to continue that cycle?

Lore Olympus itself is not responsible for the entire trend. It cannot, of course, be blamed for all these stories existing in the current narrative. But Smythe did take a rapist character and rewrite him into a sweet, kind love interest, and I think even aside from being part of a really unpleasant general trend, this decision at the core of the story permeates outwards and taints everything else. Yes, the art is beautiful, the layouts clever, the storytelling pacy and the characters engaging… but it’s not enough, nor should it be, to get past the problem at the core.

The Math

Objective Assessment: 6/10

Bonus: +1 for genuinely lovely and visually interesting art style

Penalties: -3 for rapist rehabilitation attempt

Nerd Coefficient: 4/10 not very good

Bonus: +1 for genuinely lovely and visually interesting art style

Penalties: -3 for rapist rehabilitation attempt

Nerd Coefficient: 4/10 not very good

Reference: Lore Olympus Rachel Smythe [Cornerstone, 2021]

POSTED BY: Roseanna Pendlebury, the humble servant of a very loud cat. @chloroform_tea