Today we welcome Ian Sales with a guest essay for Dystopian Visions! Sales is the author of the award-winning Apollo Quartet (see our glowing reviews of this must-read series: here, here, here and here), and founder of the SF Mistressworks blog. He can be found online at iansales.com and tweets as @ian_sales.

The Road to Dystopia

There is a famous road paved with good intentions, but it is a very different sort of path which leads the way a dystopian future. We know the signs, we’ve seen them before--if we’re not old enough to remember them, then we’ve studied them in the classroom. Yet people these days seem all too happy to treat those warning signs lightly. And I have to wonder:

How much of that is science fiction’s fault?

True, there are several well-known cautionary tales - Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is the obvious ur-text, but there’s also Zamyatin’s We, Karp’s One (though its concept of dystopia seems clearly aimed at a subset of US readers), Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange... none of which, of course, were published as science fiction, although they have been claimed by the genre. But there are also plentiful dystopian novels that were published as SF--Fahrenheit 451, The Space Merchants, Stand on Zanzibar, High-Rise… and, more recently and much more widely-known, The Hunger Games trilogy, which was published as YA but is widely recognised as science fiction.

Three science fiction novels spring to mind as examples, published in 2011, 2013 and 2014. One was by a highly-regarded genre writer, who has spent the last twenty years writing fiction not actually published as science fiction. Another was written by a successful British author of space operas. The earliest of the three is also a space opera, the first in a series of, to date, six novels, which was adapted for television in 2014.

In each novel, there is one small, almost throwaway, element - a piece of background, a minor plot point, something which is either not needed or could have been achieved by other means – relevant to this piece.

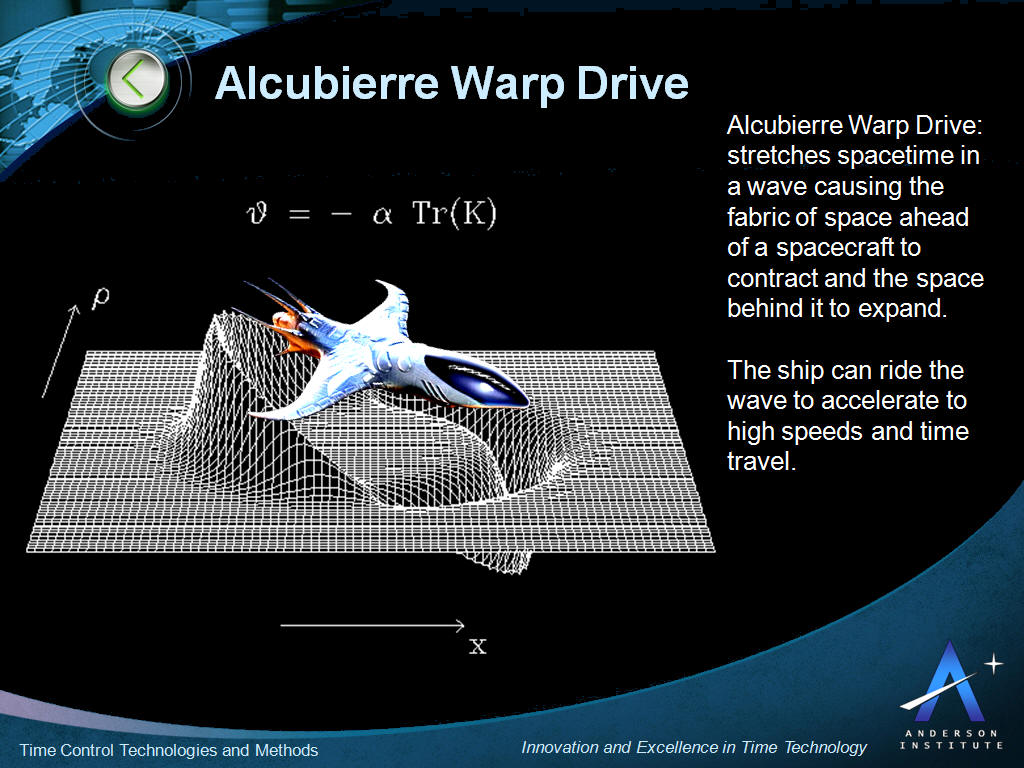

In the first novel, the one published in 2014, a means of communicating with the relatively recent past has been discovered early in the twenty-second century. However, the act of communication, as in Schrödinger’s thought experiment, creates a new timeline which cannot lead to the communicator’s future. And so a “hobby” has grown up around this, with people of the twenty-second century using their more advanced knowledge and technology to interfere in the iterations of the early twenty-first century they generate. In a throwaway line in the novel, a character mentions one person who creates alternate twenty-first centuries with the sole intention of testing weapons technology, forcing the world of each past into a global war, so that he might harvest the fruits of its desperate technological struggle for survival. What the novel fails to point out, however, is that this “hobby” is playing with the lives of six billion plus people in every single one of the alternate worlds, often to fatal ends.

The plot of the earliest of the three novels revolves around an alien virus discovered on a moon of one of the gas giants. An executive of a powerful corporation is keen to learn the actual effects of this virus, and has decided that laboratory tests can tell him only so much. So he hires a group of mercenaries, seizes control of an asteroid community with a population of 1.5 million people, introduces the virus and seals the asteroid. In other words, the executive consigns 1.5 million people to death, a particularly horrible and gruesome death, in an effort to find something which might prove profitable.

In the third sf novel, published between the two mentioned above, a young woman’s peculiar origin is important in a billionaire’s plan to regain his former political position. But he can’t simply ask the young woman to help, as she has an important public role to play in her culture. He must kidnap her. And in order to hide her disappearance his agents crash a spaceship into the ocean, causing a tsunami which kills tens of millions of people.

The three books are: The Peripheral by William Gibson, published in 2014, Leviathan Wakes by James SA Corey, published in 2011, and Marauder by Gary Gibson, published in 2013.

Since its beginnings, science fiction has exhibited a blithe disregard for the characters who people its stories, outside those of the central cast of heroes, anti-heroes, villains, love interests, etc. Frank Herbert’s Dune from 1965, for instance, describes how Paul Muad’Dib launches a jihad across the galaxy which kills billions. EE ‘Doc’ Smith’s Second Stage Lensman, originally serialised in 1941, opens with a space battle between a fleet of over one million giant warships and an equal number of “mobile planets”…

Manipulating scale to evoke sense of wonder is one thing, but the lack of affect with which science fiction stories and novels massacre vast numbers of people, for whatever narrative reason, is more astonishing. There is no commentary on the morality of such actions. And very rarely any discussion of the effect on the victims and survivors. Such consequence-free deployment of mega-violence not only desensitises the reader to large numbers of deaths, but it also normalises the thinking which results in those atrocities.

Because these are atrocities. Some might be acts of war, dialled up to unrealistic levels in order to tickle the reader’s sense of the dramatic, but many of them are not. The authorial lack of empathy for those millions and billions is breathtaking. True, they are fictional people, they never existed, they are not real. Indeed, they’re likely not even named characters, just part of the background, like buildings or the landscape…

There are even fictional worlds which can only exist because atrocities such as the above were committed before the story began: dystopias. Dystopias do not happen overnight. War, a fascist or theocratic regime, epidemic, climate crash… something at some point slaughtered or enslaved huge swathes of the population, and this is considered simply “world-building”. Science fiction is more concerned with the costs of dystopia on those living within it - and the genre can play an important role in that respect, although waiting for the right special snowflake to come along and save the the day is not it - than it is the events which led to it. And if the latter are discussed, it’s with a sense of inevitability - who can stop the Bomb from falling, after all - that the narrative fails to address. In most dystopian novels, the dystopia is presented as a fait accompli. It is not worth commenting on how it could have been prevented because the lesson of the narrative is either accommodation or overthrow. And the latter, while much more dramatic, is almost certainly going to lead yet more mega-violence. Often to no good effect.

No discussion of dystopian fiction would be complete without mention of a work which discusses the costs incurred on the road to dystopia. Unhappily, I can’t think of a single science-fictional example. Science fiction is not interested in “works in progress”, or protean futures, only in applecarts which can be upset or re-righted. But then a setting is little more than a backdrop against which the protagonist can be shown under the brightest of lights. Who would want to read a book in which the hero’s impact was not immediate but might take decades or centuries to manifest?

In the name of world-building, in the name of drama, science fiction has created stories where millions or billions are slaughtered on the flimsiest of pretexts (to be honest, I can’t actually think of a single acceptable pretext), or where villains have a single setting: psychopath. The more such stories readers see, the more readers become inured to these sorts of actions. But that’s not what fiction is for, and certainly not what science fiction is for.

Someone once said dystopian fiction plays an important role because it shows the privileged what the lives of the unprivileged are like. And yet so little published dystopian fiction actually meets that description. Science fiction has spent over a century reinforcing the prejudices of its readers, and all the while it has claimed to be “challenging their horizons”. It is an astonishing sleight of hand.

Not, of course, that science fiction is unique in popular culture in doing so.

However, science fiction at least has the advantage of an active community of creators and consumers. So instead of telling stories of genocide and mega-violence and psychopathic villains, throw a little empathy into the mix. When writing war stories, show the cost on all involved, not just the hero. Don’t escalate the violence while blithely ignoring the morality.

Let’s all be responsible about what we read and write, because it does matter.