The Meat

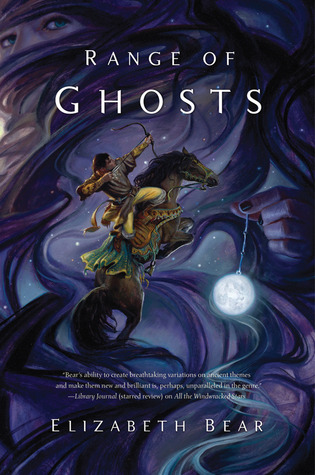

I have to start with a mea culpa: I wrote the bulk of this review more than a month ago. I've left it languishing since then, for the simple reason that I've been afraid that I won't do the book justice. Range of Ghosts is a complex and deeply rewarding book, and it moved me in a way fantasy books don't generally move me. It is one of the best fantasy books I've ever read and, really, should have been on last year's Hugo and Nebula shortlists. It wasn't--a fact that baffles the hell out of me.

Range of Ghosts and does not take place in the typical alt-Western world where most epic fantasy takes place. The decision by a Western writer to base a fantasy world on non-Western cultures and/or mythologies, of course, is a high-risk/high-reward strategy. High-risk because you presumably didn't grow up in that culture or with those mythologies, which in turn means there's a greater chance you'll get things wrong. And given that non-Western cultures and mythologies are marginalized in SF/F, those mistakes can be troubling or hurtful in ways getting it wrong about, say, medieval France or England simply would not be. All that said, if you can pull it off and do justice to underrepresented subjects and cultures, you've not only produced something inherently more interesting than yet another Euro-fantasy, but also helped expand the boundaries of what's considered acceptable and normative in our sometimes painfully Eurocentric corner of the nerdosphere. Maybe you even encourage readers to start learning about places, times and peoples they might have known little about (or casually accepted stereotypes for) as well.*

This is one of the strengths of Elizabeth Bear's remarkable "silk road fantasy." For the unaware, Bear has long been a part of the public discussion on issues of representivity and appropriation. She's clearly learned from those experiences, and as a result produced a fantasy set outside the alt-West that gets it about as right as any such book produced by a Westerner has ever gotten it.

While it may not be historical fiction, the peoples and polities found in Range of Ghosts are all firmly rooted in real-world analogues. Though Bear does not agree (as she told me on twitter in polite but not uncertain terms), I'd call the book "historically-grounded fantasy." After all, it's not just that the Qersnyks (Mongols), Uthmans (Abbasid-era Sunni Muslims), Rasans (Tibetans) and others are firmly rooted in real-world analogues, but that they share extensive political and social institutions and cultural concepts with their real world analogues--and are spaced out geographically in roughly the same way they were spaced out in actual human history (albeit anachronistically in some cases). As such, I see Range of Ghosts as having a firmer foundation in stuff that really happened and people who actually lived than a lot of fantasy. What's more, Range of Ghosts consistently pushed me to seek out and consume as much historical knowledge about the cultures and mythologies she draws from as I could find. So as a side-effect of reading this book, I now have a much more nuanced and rich understanding of Mongol history, among other things.

All that said, a majority of the cultural soup contained in the book is made-up, and the world-building is a particular strength. Bear introduces us to a reality in which peoples are watched over by gods whose domains correspond to the extent of their chosen people's political reach. As a result, each region along the Celadon Highway is covered by a different sky, and the book's characters grow disoriented as they leave the comfort of their spiritual domain. The effect is to establish religion as an essential component of the ecology--no less important than topography or climate. The device also works as a literal interpretation of the disorientation felt by religious minorities, presumably much more acute in eras more deeply enchanted than our own. I could go on, but then I'd go on for much longer than I have room for. Suffice to say that, in a genre drawing heavily on an era of totalizing religion but which tends to treat the subject with a trepidation bordering on ambivalence, Bear's portrait of faith as a lived reality stands out as an unusually sensitive, nuanced and sympathetic portrayal of the deeply religious.

Plotting in the first half of the book is a bit elusive, but deliciously so. We start off with protagonist Temur waking in a field of bodies, a strange horse by his side and a deep gash across his throat--which, really, should have killed him. He looks to the sky and, by the arrangement of moons, comes to realize that his cousin, in whose army he rode, is dead. However, his ambitious uncle Qori Buka, who led the opposing army, is still alive. This doesn't portend well for Temur, so he tries to hide in a refugee column. Here he meets Edene--an independent and worldly Qersnyk woman to whom Timor immediately grows attached. Unfortunately, Qori Buka's ally, the wizard al-Sepehr (alt Hassan-i-Sabbah) dispatches ghosts who steal Edene from him. Temur swears he'll go to the ends of the Earth to find her.

By the gates of the city of Qeshqer he meets Samarkar, once Princess of Rasa and now a wizard, and Hrahima, a sentient Tiger in the service of a merchant-prince (of sorts) from Messaline. Hrahima seeks to warn all of al-Sepehr's ambitions to resurrect the long-dead and universally-feared Carrion-King. Qeshqer, though, is a ghost town and, what's more, there's evidence that its people fell prey to the same ghosts who took Edene. From this point on, Range of Ghosts adopts a more traditional quest structure--one that takes our heroes to Rasa, to an ancient and isolated mountain kingdom and across the known world.

Though the book moves more quickly from this point forward, I found the shift to this familiar narrative form a bit disappointing. That's not to say there's anything wrong with it, but rather just that I found the dense, surreal and expressionistic storytelling of the book's first half to be such a breath of fresh air. It reminded me of The Book of the New Sun, which I guess would be the Holy Grail of compliments for any fantasy author with literary aspirations. As the pace picks up, some of that dissipates. In its place, simply an unusually well-written and gripping adventure with more depth and smarts than nearly anything published in the genre. I know: poor us, right?

At the end of the day, though, the fact is that this book just does so many things right. The prose is just wonderful--tight and compact yet poetic at the same time. The characters are well-rounded, relatable and sympathetic, and you feel as if you have a stake in their relationships. The settings are evocative, the cultures internally consistent and the battles thrilling. And, as described above, Bear is not afraid of presenting vastly different social relations from those we see as normal for epic fantasy, nor of exploring the implications of these things in a suitably contextualized manner. As you may know, this is a big thing for me.

I did, however, have one area of concern. Though gender, ethnic and class dynamics are generally treated with due diligence, I found myself growing a bit uncomfortable every time the Uthmans or the Nameless Cult came up. The Nameless are, after all, positioned as the bad guys, and the Uthmans are essentially "othered" by the Qersnyks and Rasans who make up the bulk of the book's characters. So as things stand we appear to have alt-Muslim "baddies" and alt-Muslim "weirdos," and I'm just, well, a bit tired of this trope. That said, I do think it's just a setup; I fully expect that in later volumes, Bear will approach these alt-Muslim cultures with the same sophistication she reserves for the Qersnyks and Rasans in this one. So I guess you can take that as conditional criticism only.At the end of the day, though, the fact is that this book just does so many things right. The prose is just wonderful--tight and compact yet poetic at the same time. The characters are well-rounded, relatable and sympathetic, and you feel as if you have a stake in their relationships. The settings are evocative, the cultures internally consistent and the battles thrilling. And, as described above, Bear is not afraid of presenting vastly different social relations from those we see as normal for epic fantasy, nor of exploring the implications of these things in a suitably contextualized manner. As you may know, this is a big thing for me.

That aside (and word on the street is that the above hunch is correct), this is a remarkable book, one that does nearly everything I want a fantasy book to do. It's a book you should read, if you haven't done so already. In fact, you should do it right now. After all, Range of Ghosts is so good that I've gone ahead and made it the first novel reviewed on this site to ever garner a perfect score.

The Math

Baseline Assessment: 9/10

Bonuses: +1 for the incredibly rich world-building; +1 for depth of characterization.

Penalties: -1 that conditional criticism.

Nerd Coefficient: 10/10. Mind-blowing/life-changing.

[See explanation of our non-inflated scores here.]

*This does not obviate or lessen the need for more published works by non-Westerners. Good Western-written books drawing on non-Western histories, cultures or mythologies can help broaden our collective sense of what subjects are accepted in mainstream SF/F, but they do not broaden the range of voices. If you are interested, as I am, in supporting the expansion of SF/F to include more voices from beyond the West and Anglophonia, you can start by checking out The Apex Book of World SF (vol. 1 and 2), become a regular reader of The Future Fire and spend some quality time at Lavie Tidhar's and Charles Tan's excellent World SF Blog. There's lots more out there, but those are good places to start.