Right in the heart of brimming awards season, we come to the Clarke Award shortlist, whose winner is due to be announced on the 25th of June. While we wait to find out the winner, myself and a very exciting guest decided to read the shortlist, and see what we think of the nominees as individual books, a group together, and as part of the wider fiction conversation of 2024 and 2025.

Joining me for this discussion is 2024 Clarke Award nominee, Hugo winner, Astounding Award Winner, World Fantasy Award winner and excellent-opinion-haver, Emily Tesh!

Per their website blurb, the Arthur C. Clarke Award is given to the best science fiction novel published in the United Kingdom during the previous year. As a juried award whose judges come from a variety of UK groups - the British Science Fiction Association, the Science Fiction Foundation and the Sci-Fi-London film festival - one of the key features is its ability to pull up gems that might not have made it onto popular voted awards, placing them alongside more well known authors and works, and giving a different slant on the year’s SF - as evidenced by this year’s shortlist, some of whom have (at least so far) not been honoured elsewhere, and sit here alongside Hugo Award nominees.

This year, the shortlist is as follows:

Private Rites by Julia Armfield

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

Extremophile by Ian Green

Annie Bot by Sierra Greer

Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Thirteen Ways to Kill Lulabelle Rock by Maud Woolf

Emily and Roseanna got stuck into the shortlist and come here to share their opinions on the novels, the shortlist as a whole, and what the Clarke is covering that other awards may be missing, as well as their thoughts on who they might want to win.

Roseanna: Shall we start by going right in there, rather than a gentle introduction? I want to kick off with Annie Bot by Sierra Greer, because it’s one we both had a lot of opinions about, and that we kept on coming back to to think about more for days after we’d finished it.The story follows the titular Annie, a robot girlfriend owned by a man named Doug, who has been slowly developing in her complexity since she was put into “autodidactic mode” two years previously. We spend time immersed in her perspective, as she struggles with what Doug wants from her, how to please him, as it runs up against her own growing and individual desires. A meeting with one of Doug’s friends - and a secret, somewhat coercive sexual encounter with him - kickstart a lot of painful, traumatic and dramatic events for Annie, changing her life immeasurably and leading her to think outside the rigid confines of the existence she’s always known.

For me, it didn’t fully work. There are a lot of ideas thrown up across the book, a lot of side-threads into different angles on the central metaphor of Annie’s robot nature, but overall, it feels like an abusive relationship novel that is being undermined by all these different pieces that aren’t necessarily pulling in the same direction as the central ideas. I’m not sure how the AI parts work with that premise, rather than muddling it.

Emily: One thing that really jumped out at me from reading the whole shortlist was the primacy of metaphor in the shortlist's approach to science fiction. I don't think a single one of these novels asked the reader to take a speculative concept purely on its own terms. Whether it's artificial intelligence, cloning, time travel, or climate fiction, the reader is expected to join the dots in a kind of extended simile: this thing in the story is like this thing in real life, and this is like this, and this is like this. So I spent a lot of time thinking about the function of the speculative metaphor and the ways it can fail. Annie Bot is a book where the central metaphor did not succeed for me, and this undermined my entire reading experience. Annie is a robot, an artificial person. She was created to provide sexual satisfaction and emotional companionship for her human owner. She spends the novel struggling with what this means–what does it mean to be owned, what does it mean to be a person, what does it mean to create herself as the kind of person whom Doug wants her to be. And I spent the novel struggling with what the actual point of the metaphor was.

Is the book arguing that straight womanhood is essentially false, a performance rooted in misogyny created by and for the benefit of straight men? (There are many, many sequences of Annie lusciously self-objectifying as she tries on different outfits, wears different kinds of impractical sexy underwear, simulates orgasm for Doug's satisfaction.) Is it trying to say something about transgender identity? (At one point, Doug and Annie attend couples's therapy; Doug points out that the therapist is a trans woman, and asks Annie if she noticed; the implication is that he longs for Annie to 'pass' as a human just as the therapist 'passes' as a woman; later he assures Annie that he doesn't mind that she can't have children, they can adopt, his family will never know; I wrote, with a large question mark, TRANSMISOGYNY METAPHOR THEN?) Or are we meant to read Annie's repeated fascination with the idea of her own artificial mind placed in a male robot body as a transmasculine identity suppressed by the requirements of Doug's patriarchal ideal of what his perfect girlfriend should be? Or, no, wait, is the book actually trying to be about race? (Annie's appearance is a copy of Doug's ex, but whiter; the entire emotional arc turns on a question of how she can ever escape her enslavement by this man.) Because in each case I found myself wondering–so what are we saying about trans identity, what are we saying about race, what is the book actually saying about any of the ideas it touches on; is it really saying anything at all?

It is saying something. When I was growing up my mother had a shelf of books she called the Ain't It Hard Being A Woman shelf. Annie Bot would fit right in. It's terribly hard being a straight white woman with an abusive boyfriend. Leave the boyfriend. I'm still not sure why she had to be a robot about it.

I think this struck me particularly hard when read in contrast with another book on the shortlist that manages its central metaphor with striking deftness. The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley is a book about being a lone survivor of a disaster, pulled out of the familiar and into a world of terrible ease and mundanity where your past makes you a perpetual stranger; it's about being a refugee from history, a person struggling constantly with hereness and thereness, reckoning with the world created by imperialism from a position of safety, comfort, and collaboration which you'd rather not think about too hard; it's about being lost, in time and space, forever. Also, nineteenth-century Arctic explorer Graham Gore is there.

Which is to say: I thought this book was spectacular. Bradley knows the thematic work she wants her metaphor to do and she goes to work with a scalpel, unpicking every layer of 'refugee from history' with perfect sharpness. The book's conceit is that the narrator is a bureaucrat selected to keep an eye on Graham Gore when the Ministry abducts him from history at the moment of his disappearance in the Arctic, incidentally killing the rest of the mission. Then they fall in love. But the book is about the experience of living in Britain as the mixed race child of a refugee who escaped genocide in Cambodia. Why does the narrator fall in love with Graham Gore: well, how could she not? They're the two most different people imaginable (a classic of romance, which I always like to see done well) and thanks to the Ministry's decision to abduct him from history they are also fundamentally Exactly The Same.

This is a debut novel for Bradley and I can't wait to see what she does next. It's very, very good. It's extremely funny. The thematic work is beautiful. It does fall apart a little in the last fifty pages–speaking as a person who has done a time travel plot: dear god is it hard to manage all the moving pieces of a time travel plot in a satisfying way. I almost wish Bradley hadn't bothered. I would have been happy with just the romance, the jokes, the brutal thematic underlayer, and the moody descriptions of the weather.

Roseanna: If Annie Bot is a shotgun, then The Ministry of Time is a scalpel. Or possibly a hammer. In any case, I entirely agree - it knows precisely what it wants to be and then goes at it at an unapologetic full tilt. Every single piece of what feels like such a disparate set of genre-components all eventually turn towards the job of supporting that one thematic core of the exploration of “refugee” as a concept. Bradley uses different ideas extremely skilfully to triangulate on her points, and never more clearly than in the three characters whose different experiences of racism in Britain come up throughout the book. The first is the unnamed main character, for whom that racism permeates all aspects of the story, and not least her relationship with Gore, whose vocabulary and approach to race are entirely drawn from his historical context (more on that in a moment). She keeps her head down, and her path is one of survival, just getting through it with the least impact and harm on her as possible. By contrast then, are her sister, whose emotional working through of her own experiences the main character disparages in her thoughts, or Simellia, a colleague at the ministry who offers the protagonist solidarity (and is rebuffed), and has a much more resistance-minded approach to the constant impacts they both suffer throughout the story and beyond. Three ways of existing under racism, three conflicting and contrasting approaches. The narrative does not commit to a clear model of which is correct - however much the story does not always support the protagonist in her (often terrible) choices, there is always an understanding for how she got to where she got - but does always give an insight into why, and uses the triangulation of the three separate approaches to deepen our understanding of all three as characters, especially by their interactions with one another. The frustration palpable between Simellia and the protagonist as their different approaches slide past each other, the fundamental misunderstandings of this person who should get it but doesn’t, forms a critical part of us seeing each of them as the person they are.

And, because Bradley seems to love efficiency with her many tools, is an obvious thematic crossover with the frustrations faced in working with someone from the past.

This, too, I think she does amazingly. It is so hard to find books that incorporate historical characters or settings that get historicity right, and I think Bradley has done a remarkable job here of something that could have gone wildly wrong - making Gore both authentically of his time and intensely charming and likeable and interacting authentically with the modern-day context. I never lost a sense of him throughout the book as coming from a particular context - and the same is true, to a lesser extent, for the cast of supporting historical figures pulled out of different pieces of history alongside him - and having his whole self be a product of that context, for both good and ill.

It means we get a romance with someone who feels like a whole person, not with a projected retrofit of modern morality, but with their own sense of identity and self that does not always fit neatly up against the protagonist’s. That, alongside the way Bradley crafts the atmosphere in which they interact, makes it a far more successful romance for me than many others I’ve read.

And then, speaking of atmosphere, she does just as good a job of crafting the sense of place - the hereness to contrast Gore’s thereness - of this nebulously near future London baking in a heat that is familiar but intensified. Writing in Zone 3 now as the temperatures climb into uncomfortable summer, the miserable claustrophobia of some of the midsection of the book feels only just that tiny bit out of reach - a horrible prescience on what is to come that provides the contextual realism as well as the atmosphere and helps ground the more fantastical elements of the story.

Which brings us nicely along to one of the other bangers of the list - Private Rites by Julia Armfield. It’s on the other end of the weather spectrum - every single review I’ve read of this book, including my own, starts with the constant rain in the story on the first line and for good reason - but it forms an atmospheric substrate in just the same way as in The Ministry of Time. And these aren’t even the only two near-future horrible-climate Londons of the shortlist.

Where The Ministry of Time reaches out of SFF and into romance, spy thrillers and contemporary literature, Private Rites has more than half an eye on horror and literary fiction, and it’s from the interaction of the SFnal elements - climate fiction - with those two that I think its greatest strengths lie. It presents climate change not as a novum, not as a problem to be solved by daring heroes, but something akin to an act of god. It’s a prompt for psychological exploration and a backdrop for the melancholy lesbian sisterly shenanigans that take up the centre stage of the majority of the plot.

Emily: Private Rites is such a very assured, intelligent, well-crafted book that I feel a little guilty for not liking it more. This is not the only book on the shortlist I have this feeling about (more on that later) but I think this is perhaps the book you and I disagree on the most, because I know you really loved it and I just thought it was pretty good. It is absolutely leaning on literary fiction–Armfield's prose is strong. And it's another one which is doing thoughtful, complex, interesting things with a central metaphor. The conceit Armfield has borrowed from horror fiction is: what if there was a mysterious guy secretly in your house, would that be spooky or what? Sometimes the Guy is your father and the house is the emotionally horrific architectural masterpiece he built to refuse the effects of the climate crisis. Sometimes the Guy is your half-sibling and the house is the drowned and ruined and still madly functioning remains of London. (I did really enjoy the layers of sibling relationships in this book: it acknowledges, as few books do, that sometimes a much younger or older sibling is simply a person you don't know very well who was, unfortunately, also there.) Sometimes the Guy is God, maybe, and your house is the ecologically devastated planet?

Also–spoilers–sometimes there is literally just a spooky mysterious bad guy secretly in your house.

I saw this outcome from a long way off, which is not necessarily a problem. Horror sometimes turns on anticipation! Unfortunately, I found the reveal more comical than spooky in the execution. That's actually something this book has in common with The Ministry of Time–both succeed better as literary fiction (with their interest in language and human behaviour, and their layered, considered thematic complexity) than as genre fiction, because both of them do the genre fiction plot in the most underbaked and obvious way possible in the last fifty pages. Private Rites actually made me think a bit about 'science fiction' as a category. (Of course, people are constantly thinking about science fiction as a category; a bad habit of the entire genre.) I found myself dwelling on the 'science' part, on the suggestion that the fiction of the future is necessarily a fiction of science, which has always struck me as an oddly triumphalist understanding of how history and technology interact with one another. Private Rites is staunchly unscientific. I like the book better for it.

Roseanna: That was one of the things that really struck me as I was reading it, and I haven’t got a better way of explaining it than thinking it’s climate fiction but not science fiction (which is awkward, given what the Clarke is for). I think that is something of a contentious take, and drilling into it would be a whole “what is SF anyway”, leading me straight into that bad habit as well, but my short, high level version is pulling on that “fiction of the future” piece. Climate change is rapidly becoming the fiction of the present, not the future, and so it’s resolving into non-SFnal genres more and more often now. Especially in Private Rites, where the imagined future on display is non-specific and very proximate-feeling, I think that veneer of futurity is about as thin as it could possibly be. It’s climate as spectre of the current zeitgeist (in the way that all fiction about the future is actually concerned with the now), just with the dial turned up a little way. So I think this is a case of the future catching up with the genre - clifi may once have been a disastrous science fiction prediction, but it’s now just horrible reality.

Which is a long way of saying - I absolutely agree, it’s litfic first and foremost. Where I disagree (maybe) is that the genre it rushes into at the end is horror more than it is SF. We see the seeds of it through the latter half of the book, in the intrusions of inexplicable oceanic life into the scenes from the city’s perspective (which, incidentally, are some of my favourite parts of the book - I love weird descriptive sections, and these are brief but very atmospheric). It explodes out in the final confrontation, but I think it was an undercurrent (sorry) for a while beforehand.

I think I was a bit more into it than you, but I have been an enjoyer of Julia Armfield’s brand of melancholy lesbians encountering the uncanny for a while and was entirely primed for it.

Emily: I am tragically impatient with the sorrows of melancholy lesbians. It's probably a personal failing. And now, moving to another book which I filed under 'well this is very good and I feel bad that I'm not more into it': Extremophile by Ian Green is the story of yet another near-future ecologically-ruined London, and of the underground world of criminals, indie bands, ecoterrorists, and biohackers who survive beyond the still well-cared for Zone One. The book moves vividly and competently between the heads of its narrators–Charlie, a biohacker who plays bass in a band; the Ghost, a powerful corporate executive; Scrimshank, a brute; the Mole, the sole survivor of a horrific biohacking experiment. The character work is really, really good. I found the Ghost's chapters genuinely hard to read: there is some real stare-into-space body horror, framed coldly and painfully in the point of view of a man who thinks himself extraordinary and is constantly mentally workshopping unfunny little jokes.

One cannot accuse Green of underbaking the plot. This is a heist book, and heists rely on tight, propulsive plotting. It's a heist book where the most attractive character is named Parker and there is a Nathan floating around in the background, which made me laugh. The book winks at you: we've all seen Leverage. In fact, referential is a word that kept coming to mind. This is a book that made me stop and DM Roseanna to make her listen to The Mountain Goats. (The song you need. You'll know when you get there.) This book enjoys both Leverage and Le Guin (the word for world is–). Maybe the referentiality is part of what made the book feel so strangely nostalgic to me. Extremophile is set in the future, but in the future London has a lively indie punk scene where young people gather to fuck and dance and plan their environmental protests. The narrative loves a thriving independent live music scene, writes from a place of affection and knowledge about it, in a way that felt so entirely real and tender that it also felt, somehow, more like the past than the future.

But this is not the only thing nostalgic about Extremophile. Unlike The Ministry of Time and Private Rites, this is near-future climate-inflected science fiction where the science is front and centre. Our protagonist and chief narrator, Charlie, is a scientist. Underneath the slick machinery of the heist plot, the book asks questions about how much it actually matters to do the science: to be a scientist, to love knowledge, to look at the natural world with care and attention–a tree, a pigeon, a marsh spreading through Hackney–to quantify, analyse, and create, as a scientist. Charlie begins the book doing shit science, exploitative nonsense–here's your zodiac reanalysed in light of your DNA–squeezing money from the gullible with a mix of fact and fiction designed to give idiots what they want. The monstrous Ghost with his custom-designed biological cruelties is only the logical conclusion of the path she's already on, and on some level Charlie knows it. It's no wonder she's a nihilist. The question is whether she's wrong to feel this way, in a world where science has already comprehensively failed to save the day.

In other words, I read this book and went 'aha, this is definitely Science Fiction'. (You know it when you see it.) And that also felt nostalgic to me! I found I was a lot more interested in the Science Fiction than the heists, and my sympathy for Charlie grew through the book. And I thought the London of the book was perhaps the most persuasive and aesthetically powerful of all the near-future Londons we read for this shortlist; the book has a really extraordinary sense of place. So why, after several paragraphs of well-earned praise, was I not actually all that into Extremophile? Well, I feel like I got handed a first-rate scotch and now I have to sheepishly admit I don't like whiskey. Heist plots don't do it for me–I have to be in exactly the right mood to watch Leverage. I find most live music an exquisitely miserable experience thanks to my loathing of crowds and lifelong hearing difficulties. Bio-horror freaks me out so much that I kept having to put the book down for a bit after the Ghost chapters. You see the problem?

Roseanna: Not to add another problem to the mix, but the thing that hit me right between the eyes while reading Extremophile was: this is cyberpunk. It’s not. It’s not about the tech in the way classic cyberpunk is. It’s bio far more than it is cyber (is biopunk a thing? Everything -punk is probably a thing if you try hard enough, much to my despair), but the atmosphere, the anti-corporate-ness, the unregulated techno future full of violence and individualism and fancy crimes? That’s cyberpunk. And that was what gave me that big nostalgic whiff, alongside all the science.

It’s just unfortunate that I don’t like cyberpunk at all. I also don’t really get a heart-squeezing burn of affection for the live music scene (I too hate crowds, but also my taste in music is simply atrocious), I don’t like heists - especially watching people plan them, I don’t like extended scenes of violence and fighting, and I generally struggle with climate fiction. It felt like a recipe for me to absolutely hate Extremophile.

And yet… and yet. You’re right. It is entirely embedded in this futuristic, muggy London that I can fully believe and feel as I’m reading. Charlie’s journey from nihilism to tentative hope is genuinely touching and emotive. The characters all have wonderful, distinctive voices when it’s their turn to be the viewpoint, and each provided something different to the narrative to make their inclusion worthwhile. One of them - Mole/Awa, a physically and genetically altered woman upon whom those changes were enacted forcibly in her childhood - gets some absolutely gorgeous writing that made me want to linger over every sentence. By the end, all of that somehow managed to charm me into liking it, against all my native inclinations. Not all the way to loving it. But a lot lot further than I ever would have expected from someone giving me a plot summary.

If it has a failing (and that failing isn’t just “me”), I might suggest that the ending could do with dialling back a little on the sentiment, but given by that point it had worked its hooks into me, I can’t complain too much. It does the legwork of grounding all of its climate work in very realistic pessimism, and doesn’t let its resolution drift into the sort of world-changing optimism that would have been at cross-purposes with its ongoing messaging. The world is still shit, it says, but maybe it’s worth fighting anyway. And, critically, maybe Charlie thinks it’s worth fighting now. It works extremely well on the level of one person’s path back to resistance and action against the injustices in the world around her. Like Private Rites, it’s a book interested in the human, and the human experience of *gestures* all this.

So I think I prefer Private Rites in the end, but it’s an aesthetic preference far more than a qualitative one. Clearly I just prefer the rain.

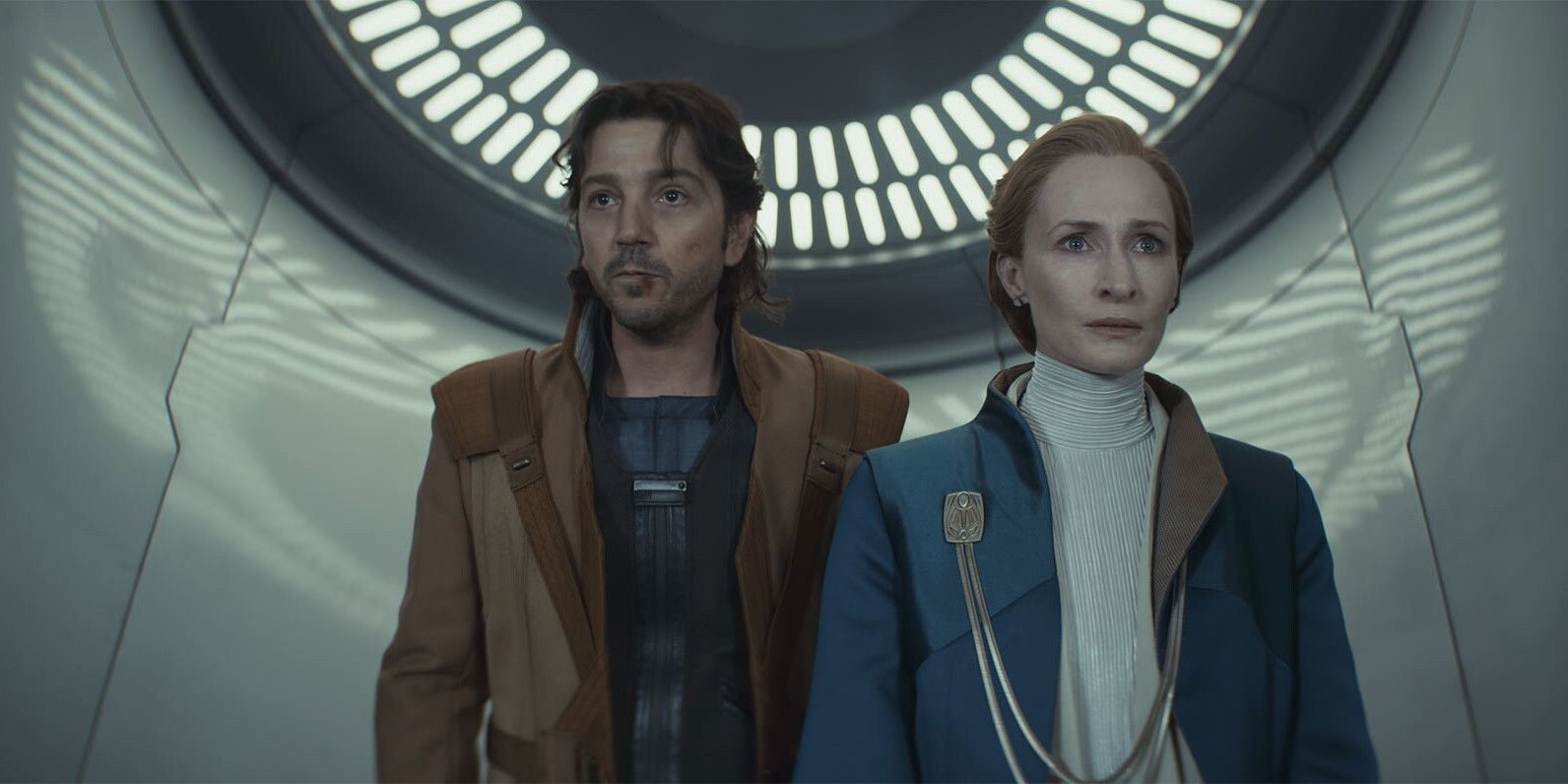

.png) |

| Actual footage of Roseanna reading Extremophile and Private Rites |

But climate isn’t the only common thread in this shortlist. There’s a common line of “hellscape (possibly techno) ravaged or being ravaged by capitalism” that links back up to the remaining two, both of which also join up to Annie Bot by being personhood stories.

Starting with the more obvious overlap,

Service Model is another robot servant story, though this one far more in the traditional mode of robotic servitor (Uncharles) who must obey his programmed task hierarchy, even as the situation he’s in spirals further outside of his control, and the frame of reference his programming can encompass. It’s a story of a journey - a set of connected vignettes in different, equally unexpected locations - as Uncharles the robot grapples with his existence after the death of his master, with a bit of free will and agency thrown in for good measure.

I have two problems with it. The first, the ever-tricky sense of humour. The book is very much trying to use the surreality of the scenarios Uncharles finds himself in to generate comedy. That comedy, unfortunately, did not land with me. And when most of the jokes tend to draw from a common thematic pool… they continued not to land for me the whole way through.

The second thought is that I struggled with what this book was really trying to achieve, and why it took a whole novel to do it. SF has, over the years, done the “am I a person?” story to death, whether from robots or clones or any manner of other person-adjacent consciousnesses. Personally, having been on this ride a number of times, I am primed for the inevitable answer of “yes”. When is the answer not “yes”? I’m not sure, unless you’re really pushing some boundaries (or hey, maybe drawing on the current cultural consciousness and “AI” situation), what can be added to this narrative? And I don’t think Service Model does. Instead, it’s a set of mildly comedic scenarios strung together, with a bit of a conclusion at the end about societal collapse (turns out, the free market doesn’t solve everything and capitalism may, in fact, be bad - see the aforementioned hellscape).

Emily: The trouble with being as good and as prolific as Adrian Tchaikovsky is that the person you're going to end up most compared to is yourself. Tchaikovsky released two science fiction novels in 2024. Both of them are on the Hugo shortlist, but only one made the Clarke. And I am absolutely baffled by the judges' decision to elevate Service Model over Alien Clay, because I thought that Alien Clay was a much better book–a book with more to say, and more interesting ways of saying it; a Clarkey book, as I understand the term.

I quite enjoyed the first act of Service Model. I read it thinking: aha, a light satire running on a spine of Agatha Christie but they're all robots mindlessly going through the motions of the detective novel even as the culprit in their midst confesses over and over. Charming! Funny! A sharp comment on the plot-on-rails that is also a comment on the society-on-rails! I see what you did there!

And then the book did it again. And again. And I found it less charming every time. When you got the joke the first time, it's tiresome to hear it repeated. And the book never quite expands beyond its initial conceit: here is a robot, in an absurd situation which he does not understand but which you, the reader, can smile at from your position of superior knowledge. This continues, in my very pretty hardback edition, for some four hundred pages. In the spirit of this meeting could have been an email: I do really think this novel could have been a novella. I love a novella, and Service Model could have worked really well as a very sharp, very funny, very dark example of the form, answering none of its initial questions about the failed society Uncharles comes from, making its satirical point and moving on. But as a novel, it drags. And for me, the book also suffers because I read it back to back with Alien Clay and I loved Alien Clay. Alien Clay does so many of the things Tchaikovsky is really, really good at. I loved the weird biology and the mystery of the planet and the final irresolvable moral dilemma! So why on earth would you pick Service Model for your shortlist when Alien Clay was right there?

Roseanna [lurking for the opportunity to say that Alien Clay is indeed banger]: I am boggled by exactly this same thought. I did not read them back to back, but even with a fair separation, I felt like Alien Clay was just the tighter, more controlled novel. I’d link it up to The Ministry of Time as books with a thematic hammer that know how to use them, which does feel, to me as well, inherently Clarkey. But I guess we must have something to argue with the judges about.

As something of a strange contrast, the final book

also never quite expands outside of its original conceit (at least not successfully) for me, and yet my feelings on it are far more positive - and that’s Thirteen Ways to Kill Lulabelle Rock, in which the thirteenth clone of a movie star must hunt down all her predecessors and kill them to (spoilers, supposedly) generate publicity for an upcoming film. But this description doesn’t do justice to the weirdness of that original conceit, which also contains a fair heap of musing on bodies and ownership and identity (including a scene in which the newly-woken clone looks her body over in the mirror and keeps flipping between referring to it as her own or as Lulabelle’s), some workplace comedy if the job is untrained freelance assassin, funny and sometimes startlingly real pieces of character work and, somehow, tarot. Also some self-love (but uh, not like that).

I’m not sure I could say that Lulabelle is a great book, but something about its quirky unexpectedness and ability to turn a phrase charmed me, in a way that the slightly better structured Service Model never managed. Unfortunately, I think it loses control of its threads by the time the need for an ending rolls around, but I find myself admiring the ambition, because this one does try to push some boundaries. It doesn’t succeed, but I respected the intentions a great deal.

Emily: I really liked this one! I thought it was enormous fun nearly all the way through. It did new and interesting things with the very well-trodden SFnal ground of 'who, exactly, gets to be a person?' and the structural conceit of the tarot, while silly, was silly in a grounded way: it chimed with the protagonist's own desperate need for structure, for understanding of who she was and how she could exist in the world as one of thirteen identical clones–Portraits–of a lesser celebrity. The tight structure of the book meant that it telegraphed exactly what it was going to do, well in advance. When the assassin gets a car, you know she's going to crash the car at some point. But it executed the expected beats with humour and verve. I laughed out loud at the point where the assassin finds herself face to face with two Lulabelles each insisting that she is the real one and so you have to kill that bitch, and just thinks: couldn't you two have worked this out between yourselves?

And then the penultimate twist landed beautifully. The question of who, exactly, is the real Lulabelle runs all the way through the book. Ultimately, no one is. I was genuinely moved by the way the revelation landed, and how it reframed the whole conceit of the book. The thirteen clones cease to be a vapid exercise in celebrity self-promotion and become a sadder and deeper exploration of how on earth one is supposed to manage a life well-lived, and what it means to live well.

For me the only place where this book didn't quite work was the very end, where I felt it veered into sentimentality, and a final twist that felt like a broken promise. It seems silly to say 'not enough murder' about a book where the protagonist commits so many murders, but when you have spent the whole novel signalling that there is eventually going to be a violent and cathartic reckoning with your evil creator… I felt thwarted that no such reckoning took place. Surely we could have murdered someone in the end. Of course, part of the joke of the book is that none of the murders of Lulabelle ever really seemed satisfying: as these were meaningless, unsatisfactory lives, so they ended in meaningless and unsatisfactory deaths. But I would have liked, I think, a single satisfactory death, for narrative closure. After all, our narrator's card is Death: she deserves it. I'm not picky. It didn't have to be the evil creator. We could also have murdered Lulabelle's horrid agent.

And that brings us to six books! What are your thoughts on the shortlist as a whole? Do you have a favourite? Do you have an expected winner? And are those two the same?

Roseanna: My favourite is Private Rites. I love it. I am a sucker for all the things Julia Armfield does. I went into the shortlist reading knowing this would be the one to beat, and lo, so it was. I don’t think it’s entirely my terminal optimism speaking when I think it might just win it, but I am not a reliable predictor of awards, so I’m not saying that with any great certainty.

If it doesn’t, I’d be very happy to see either Extremophile or The Ministry of Time take the win, though with a preference for the latter as I just had the absolute greatest time with it, and I would love more books in SFF to be quite this charming. How about you?

Emily: My personal favourite read of the shortlist was The Ministry of Time. I am very weak to themes and jokes and romance, and it did all of those extremely well. However, I just went back to the Clarke Award home page, which reminded me that 'the annual Arthur C. Clarke Award is given for the best science fiction novel first published in the United Kingdom during the previous year.' With that in mind, my pick for a winner is Extremophile. I think it would be a well deserved win for a book which is entirely and self-consciously science fiction in theme and intention. I also think there's great value in reading, from time to time, a very good book which is absolutely not your thing. Extremophile is not my thing but I respect what it chooses to be and I think the execution is splendid. I'm glad the shortlist prompted me to it, because I would probably not have picked it up otherwise. Also, Roseanna, you really should listen to The Mountain Goats.

Roseanna: I did! I had Tallahassee playing while I was working this afternoon. It would have possibly been fun to have it playing while I was reading as subconscious thematic overlap, but I did not plan anywhere near that well. Possibly a recommendation for anyone who hasn’t picked it up yet to try (and if you don't think you recognise The Mountain Goats, try listening to the song No Children, and you may well realise you do).

I can’t disagree that Extremophile is the best at science-fictioning. And it was the biggest surprise in reading for me - to find myself persuaded into all these things I don’t enjoy, so I’d certainly be clapping along with everyone else on Wednesday for it if so. I just find myself constantly drawn back to Private Rites for the vibes, the prose, the intensely palpable atmosphere. It just grabs me.

And that’s it! Or is it… because we are doing vry srs crtcsm we did do a nice little chart as we were discussing, so have our very authoritative, totally conclusive visualisation of the shortlist as a thematic continuum.

If you have read or are planning to read the Clarkes, we hope you have as great a time with the process as we did. The winner will be announced evening UK time on Wednesday the 25th of June, so watch this space to find out if either of us were right.

Thank you so much for joining me Emily - this has been amazing!

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Genevieve-O-Reilly-Andor-010725-2-38e011b3f1184685bc1c9df14e71f7a8.jpg)

.png)