Do you remember slow zombies? If so, you remember the long

stretch of time before 28 Days Later—a

movie which arguably did some of the most lasting work for zombies in pop

culture, next to only Night of the Living

Dead. So, yes, you guessed it, it’s time to analyze one of my favorite

films of all time. This continues The Why This Matters series, begun last time

with Alien. A note on these posts:

because I’ll be analyzing these works from a variety of angles and contexts,

there will most likely be spoilers within for the pieces that I am talking

about. If you haven’t seen/read them and wish to, avoid the post and come back

later.

First, I’ll start off by saying this, if you’re one of those

people who prefers 28 Weeks Later, then

leave now because I refuse to even acknowledge it (and this is coming from

someone who loved Intacto—by the same

director as 28 Weeks Later, and had to

come to the conclusion that she’d just pretend Weeks didn’t exist so as not to taint the other film).

28 Days Later begins with Jim (Cillian Murphy) waking up from a coma, inside a now abandoned hospital (sorry Rick Grimes, you got beat to the punch). Jim than wanders an abandoned seeming London, picking up scattered money, seeing signs of devastation but not knowing the cause. He soon learns that the apocalypse has happened--and zombies now run rampage over the city. Jim soon meets with other survivors, including the badass Selena (Naomie Harris) who warns him that in this new life, one can't hesitate before making decisions.

28 Days Later begins with Jim (Cillian Murphy) waking up from a coma, inside a now abandoned hospital (sorry Rick Grimes, you got beat to the punch). Jim than wanders an abandoned seeming London, picking up scattered money, seeing signs of devastation but not knowing the cause. He soon learns that the apocalypse has happened--and zombies now run rampage over the city. Jim soon meets with other survivors, including the badass Selena (Naomie Harris) who warns him that in this new life, one can't hesitate before making decisions.

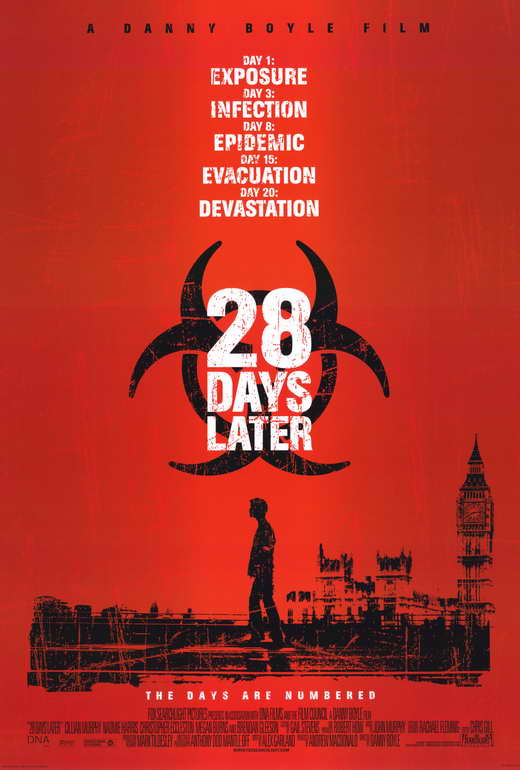

28 Days Later hit

screens in 2002. It starred Cillian Murphy, who at the time was relatively

unknown but went on to be one of our best actors ever (sorry, but he’s awesome)

and who was the only redeemable thing about Batman

Begins, and was directed by Danny Boyle—who was known for dark films, but

not at this point horror—who had made Trainspotting,

Shallow Grave, and The Beach among others. The latter of

these films remains the only Boyle film I staunchly say “NO!” to. However, The Beach led to 28 Days Later. How, you ask, innocently? Well, The Beach is based on Alex Garland’s first novel (a novel that I’ve

read so many times that I self-redact the number because I fear people would

find it unsettling) and Garland went on to write the screenplay for 28. Garland’s name you may recognize,

for reasons beyond his novels (but you should also go read his novels and

strange novelette The Coma). He made

his directorial debut recently with Ex

Machina, also wrote the screenplay for Sunshine,

adapted Never Let Me Go, and made

Judge Dredd into something that is not only watchable but is also good. Let’s

get this out of the way: I am a Garland fangirl and I don’t care what you say.

He’s perfect.

So what, beyond this pedigree, makes this is an important

film? Well, number one, it pretty much single-handedly revived the zombie genre—not

only because of the decision to make fast zombies (which is where it gets the

most credit) but also in its loving adherence to, and sincere rebuttal, of so

many of the zombie film (and, really, horror films in general) tropes. From the

way that the idea of what it is to be good/do right is twisted within the film

(yet, still ultimately upheld) to the clever take on the mansion overrun (see the

Resident Evil videogame series for

ideas on how this imagery was probably conceived) to the subversion of what

weakness is (or hesitation, in this case). It also features one of the

strongest horror movie third acts of all time: where the use of music and

lighting amplifies everything in the scene to the point that the pacing feels

sinked with one’s own, trying to keep it together, breathing.

A second point to consider is not only how this changed the

face of zombie films (which, digression time: an interesting thing to note

about zombie films and their place in Monster Theory is how the idea of

conclusion or peace for a survivor in a zombie film is the idea that one essentially

has to escape from humanity itself, seek isolation, find a place untouched by

humans who might be infected. Now think of how many zombie films there are and

try not to wonder at what that might be saying about how people currently

feel), but how it changed the face of the apocalypse genre. The Rage in the

film is something as indistinct as so many diseases in apocalypse stories, and

yet there’s a specificity there as well. Systems put in place fall down (we

have our church scene—god has abandoned us, we have our soldiers—the military

can’t help us, we have our emptied out hospitals—no one can heal us), but it is

the most primal system that remains—Family. In this case, a wholly created family

of Selena, Jim, and Hannah.

This is one reason why I argue against the alternative

ending that Boyle and Garland prefer (in which Jim dies). That ending is

certainly cyclical and works in a narrative way. However, the ending of the

theatrical release—which sees the infected dying out and our protagonist “family”

living at peace, waiting to be rescued one day or not, is the one that goes the

most clearly against the apocalypse genre—opening it up in a beautiful way.

What better way to fight against Rage than with hope?