If this is really what (being a reporter in) Japan is like, I’d rather be cleaning (or living in) a toilet!

|

| Adelstein, Jake. Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan. Vintage Crime: 2010. |

People bandy around the phrase ‘stranger than fiction’ a lot

(NB: I have no idea if this claim is statistically accurate), but it’s not often

that something written and presented as an entirely true story can actually

succeed in shocking its readers with its seeming fictionality. Why is that?

Because non-fiction writing, like all writing, operates according to narrative

conventions, and generally, the things we know belong to the category of

non-fiction don’t resemble, in a narrative sense, the things we know are firmly

in the category of fiction. Lo and behold, most of the “non-fiction” books that

do jolt us with their ‘stranger than

fiction’ vibe manage the feat by borrowing liberally from the conventions of

whatever genre of fiction writing their true story most closely resembles.

So if someone wishes to write the true story of a mystery or

whodunit, consciously or unconsciously (but probably consciously—see below) the

would-be author might drift over into the narrative world of mystery (fiction)

writing. If done poorly, this raises all sorts of red flags for the reader, because

the same markers of fictionality in a straightforward mystery novel are popping

up in a supposedly non-fiction story, and that strikes many readers as

problematic. If done well, I suppose this narrative drift might simply make the

story more of a page-turner. Either way, it’s certainly no surprise authors are

tempted to mix literary genres (non-fiction plus a fiction genre or genres),

because unless they are in academia, authors want, naturally enough, to sell

books, and presumably a non-fiction story that reads like a mystery novel will

jump off the shelves a lot faster than a painstakingly factual, dry non-fiction

story.

Suppose you had experienced more than most people’s share of

interactions with a crime syndicate, and wanted to report those experiences…in

the most riveting way possible. Would you:

A)

Limit yourself to a regurgitation of your own

notes, in chronological order, of what happened and when, and strive for an

objective tone in reporting the events, or

B)

Jazz it up a little, using “caper (fiction)

story” narrative tricks to make what happened sound more exciting?

If you chose option (A), congratulations! You’re a career

academic, and your books will sell literally dozens of copies. If, however, you

chose (B), then you and Jake Adelstein have something in common.

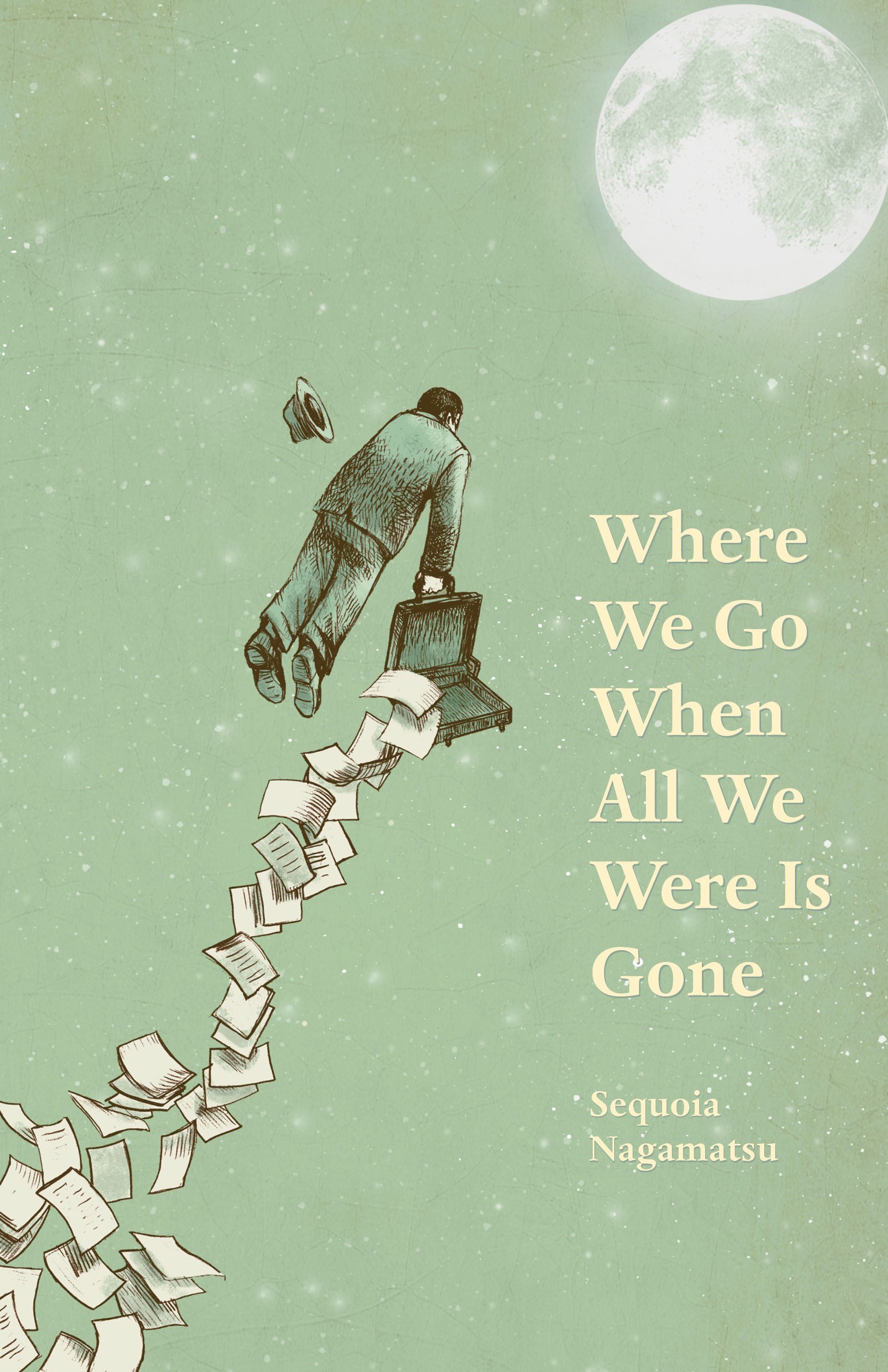

Everything about Tokyo Vice, from its cover and title down

to the witty, entertaining first-person narration, feels like a novel. In fact,

it’s so novelistic that if someone later comes forward to confess that “Jake

Adelstein” was just a literary character s/he invented, and the entire tale was

made up, I don’t think I’d be particularly surprised (though I have no reason

to believe this or something like it is actually the case, especially since

Adelstein

managed to publish his work in places like the Washington Post, an

impressive feat if imaginary!). In a way, this is a compliment to Adelstein’s

writing style, because it really was a page-turner, an in-depth glimpse into

the murky world of organized crime—and (at least to me) the even more

interesting phenomenon of the inner workings of the police-media love/hate-fest—in

Japan over the last two decades.

What about it screams “novel”, then? 1) Bribery, corruption,

international conspiracies, the FBI making deals with the Japanese mob in exchange

for information, a sort of international black-market organ trade of sorts, at

least one dirty cop, a serial killer (possibly more than one depending on

whether mob hitmen count!), “hits” on those who get in the yakuza’s way,

several physical confrontations from which the intrepid protagonist managed to

extricate himself only by violently subduing his attacker, and—it is strongly

implied—the revenge killing of one of the protagonist’s closest friends and

allies.

All of these elements, however, could have been recounted

very dryly and impersonally, but for better or worse (on balance, I think “better”)

Adelstein chose a far more engaging approach. First of all, the book isn’t

consistently in chronological order, though it certainly moves roughly “in

order”, from his early career in Japan up to the end of his Japan-based

reportage. Adelstein deserves praise for turning what might have seemed largely

rather monotonous work, of relentlessly befriending cops in order to wheedle

them into awarding an exclusive to one’s own paper, into a riveting account full

of sex, sleaze, drugs, human trafficking, money laundering, and murder. But the

question is: did he go too far in sensationalizing the material? If even half

of what he’s claiming in his book is indeed true, then the material is plenty

sensational all by itself; this reader, at least, wonders whether, say,

Adelstein humble-bragging about his “poor” martial arts skills that,

nevertheless, proved sufficient to incapacitate a yakuza enforcer/bouncer,

etc., really adds substantively to the story he’s telling.

I guess what I’m saying is that the Ivory Tower in me longs

for a thicker veneer of objectivity, of dispassionate reporting of “just the facts”,

whereas the avid reader in me crows at the deeply personal nature of the tale.

Be that as it may, this is a book worth reading, especially for anyone out

there who clings to the belief that Japan is utterly safe and pristine. Adelstein’s

harrowing account of Kabukicho and its apparently then- (and, perhaps, still

today?) rampant human trafficking of non-Japanese women, left me queasy, while

the ‘antagonist’ of the book, Tadamasa Goto, would make anyone’s blood boil

given the underhanded way he arranged his liver transplant—at UCLA, no less.

This much seems clear: Adelstein would probably have a relatively easy time transitioning

into writing fictional first-person caper or mystery stories!

Strangeness factor: 7 (on a scale from 1, A.R. Burn’s snooze-worthy

History of Greece, to 10, the life

story of Roy Sullivan,

a guy who shot himself in the head…after being struck by lightning a ridiculous

seven times over the course of his life)

This intervention between true stories and fiction was

brought to you by Zhaoyun, who loves all tales, whether they’re as genuine and

trustworthy as a degree from Trump University or just seem like they’re imaginary, and reviewer on Nerds of a Feather since

2013.