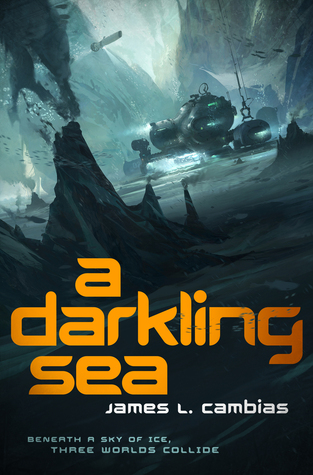

Item: Cambias, James L. A Darkling Sea [Tor, 2014]

File under: science fiction, anthopological.

Buy: Print

At some point during the transition to adulthood, I realized that questions of behavior were more interesting to me than questions of, say, whether particles can break the speed of light. But I didn't turn my back on science fiction--rather, I came to see it as a medium for exploring how behavior might change if you alter some of the key variables. Like Heinlein said, a "Simon-pure" SF story (whatever that means) is one that adheres to the following:

- The conditions must be, in some respect, different from here-and-now, although the difference may lie only in an invention made in the course of the story.

- The new conditions must be an essential part of the story.

- The problem itself—the "plot"—must be a human problem.

- The human problem must be one which is created by, or indispensably affected by, the new conditions.

- [Paraphrased as: be internally consistent in all departures from accepted science.]

Questions of how sentient alien species might behave, and how we might interact with them, provide some of the more fruitful avenues for social science fictional exploration. Ursula LeGuin's Hainish novels are without a doubt the paradigmatic examples of the anthropological approach, but you can also count Ian M. Banks' The Player of Games, Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis series or basically anything involving the Prime Directive in the Star Trek universe as well.

A Darkling Sea is James Cambias' debut novel, but it is, in fact, an evolution of previously published short fiction, most notably the 2004 story "The Ocean of the Blind"--which readers may recognize as the first chapter of the novel. The book, following from the earlier story, revolves around a scienfitic mission to the moon Ilmatar, which orbits a gas giant in a distant star system. Ilmatar is a bit like Europa, in that it's covered by 5km of ice, underneath which lies a pitch-dark ocean heated (to the degree that it is heated) by vents funneling hot gases from beneath the crust.

Somehow, humans and the relatively more advanced Sholen come to realize that there are intelligent creatures living at the bottom of Ilmatar's oceans. The Ilmatarans are crustacean-like creatures with hard shells and pincers; they are understandably blind but have advanced sonar capabilities. They have produced complex physical and social structures, and have developed a form of literacy. They even have scholars!

The humans want to study the Ilmatarans, but the Sholen are deeply concerned about anything that smacks of interference in the Imatarans' "natural development." So they allow the humans to set up a single underwater habitat, but only on the condition that they take every possible measure to avoid direct interaction. Forced by technological inferiority and the continued domestic view of the Sholen as "those friendly paternal spacepeople," accept the conditions and set up shop. Unfortunately, a vainglorious scientist/media personality, Henri Kerelec, decides to break the rules and get up, close and personal with the Ilmatarans. Things don't go as planned.

The Sholen get word of what's happened, and send a fact-finding mission to ascertain whether or not the humans can be trusted to continue their scientific endeavor without a repeat performance. But as it turns out, the Sholen are themselves mired in a complex political struggle between pragmatist-explorers, who largely share the human perspective and would like nothing more than to collaborate in their studies, and militant-isolationists, who see only disaster coming from inter-species interaction (including Sholen/human).

I won't spoil the book, but I will say that Cambias builds a remarkable conflict out of this--one that, really, has no "bad guys." Though there are certainly some "conflict entrepreneurs," to use a social science jargon term, you always get where they are coming from--even the most committed militants among the Sholen and humans. Rather, conflict arises from the failure to communicate effectively, and by the assumptions individuals bring into interaction--the meanings to our own actions that we assume others will understand, and the meanings we ascribe to the actions of others based on our own experiences and cultural practices.

There's a great scene were some humans utilize non-violent resistance tactics, assuming the Sholen will know what they are doing. But instead, the humans baffle the Sholen. After all, Sholen society is built around the concept of decision-making through consensus--affecting change from resistance and conflict are things they do not quite understand (yet are not resistant to). And this speaks to another strength of the book: its ability to convincingly portray three different--alien--modes of cognition, and making them all relatable without making them "too human."

A Darkling Sea also contains within it political theory of inter-species interaction, a reaction if you will, to the aforementioned Prime Directive. In Cambias' own words:

Did I mention I think the Star Trek "Prime Directive" is a stupid idea? I do. I know Gene Roddenberry wanted to get away from the raygun-toting empire-builders of the pulp science fiction era, but the idea of a rigid ban on any contact with "less advanced" civilizations is still foolish. It assumes that cultures without advanced technology are somehow naive or innocent, and that the process of leaving that low-tech life is a step down somehow -- a Fall from Eden. That's simply not true. When Commodore Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay, he brought change to Japan; incredible, neck-snappingly rapid change. But Japan remained Japan. Its people were no better or worse morally than before.

Taken at face value, this statement strikes me as problematic--after all, Japan might have emerged from the interaction with Commodore Perry (largely) unscathed, but at a high cost for its neighbors, who would be subjected to its violent industrial militarism for more than a half-century. And that's not even taking into account, say, those living in the Pre-Columbian Americas, few of whom could be described as emerging from their interactions with Europeans "no worse than before."

|

| This... |

|

| ...often led to this. |

Putting the !BIG IDEAS! aside for a minute, I'd also like to note that the book is very well-written. A Darkling Sea doesn't aspire to be a prose poem, but the prose is nevertheless much better than the average for the genre. The book is expertly paced, full of lively description that never ventures into the hellish realm of the infodump and kept me glued to it from the first to the last sentence. Cambias alternates human, Sholen and Ilmataran perspectives; he does so much more quickly that, say George R. R. Martin, but achieves the similar effect of making me want to skip ahead to the next perspective section for a particular character so I can see what happens right now. I also liked that the human future was suitably multicultural and multinational--not just America in Space.

|

| Not the only future imaginable anymore. |

All in all, I'd highly recommend A Darkling Sea to anyone who wants to read a book that qualifies as "hard" SF but is more interested in the social scientific implications of space exploration and alien contact. Even if I didn't love or agree with everything contained within the book, I nevertheless found it to be challenging in all the ways SF can and should be challenging.

(Oh, and if you're interested in learning more about the world Cambias has created, check this out.]

The Math

Baseline Assessment: 8/10

Bonuses: +1 for the complex theorization on communication in interaction and conflict; +1 for the brilliantly realized alien perspectives.

Penalties: -1 for Rob Freeman, the "meh" protagonist.

Nerd Coefficient: 9/10. "Standout in its category."