A story about the remembrance of the dead, through a lens of the complicated legacies they leave behind.

|

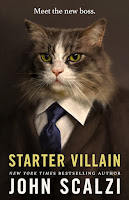

| Alyssa Winans' cover art continues to stun |

CW: Death, grief

The stories Nghi Vo has told in the Singing Hills novellas have all had a conceit, a neat little framing device that shapes the story into something a little more than just a story. It's one of the best things about the series, and means I go into each new one excited not just to know what happens, but how it's told. In the first, it was framed around found objects, the second a story told by different tellers, the third had unconnected tales that turned out to be connected by the people in them. In Mammoths at the Gates, the fourth in the series, it's stories of a person told by the different people who knew them at their funeral, stories from those who loved them, who think of them fondly, their fellow clerics, their companion and their granddaughters, who knew them only as the best they were... and one that isn't quite so flattering, but no less true.

I read this book one week after my grandmother died.

Normally, I'm not so keen to put quite so much of myself into my reviews as this, but the resonance between the story and what has happened so recently in my own life was impossible to ignore.

My grandmother was... a complicated woman. Rarely a nice one, though more often to people who didn't know her well. The legacy she left us, when she passed, was no less complex. Her will makes plain that she cared very much about lifting some of those who survived her above others, showing her favour and her disdain in equal parts. No matter how much one knows about this when the person is alive, it becomes harder to bear when you realise it's the last thing they leave in the world, the message they want to be seen after they've gone, their last word. As I say, complicated. But part of dealing with that complexity is the family that gathers at the passing, who tell their own stories about her. I haven't seen my aunt - who lives abroad - in years, but we sat in the emptiness of my grandmother's house, her and my mother and me, and naturally, what grew out of that emptiness was stories. Stories the others may not have known, or that saw a complex woman from another side than the one the listener had in their mind, or that revealed hurts she caused that the rest of us simply never knew about.

My mother asked me yesterday, did I want to speak at her funeral? I declined. I don't know how I'd even begin to frame that complexity into something appropriate for speaking publically.

Nghi Vo did.

She begins the funeral with the expected stories, the ones that praised the deceased for the things most prized by the speaker. Patience, compassion, cunning, by turns. They reveal the different sides of the person, as person in the world and later as a cleric, to the surprise of those who only knew one part of them. But the greater surprise comes in the story that is not the best but the worst of their life. The listeners all had to then reframe their knowledge of the deceased, around the discovery that they weren't, as everyone had thought, always quite so wonderful.

That sort of story is so rare, in life and in books. We do not speak ill of the dead. We certainly do not speak ill of the fondly-remembered dead, or those who were good and bad in parts*. But as Vo shows, there is incredible power in remembering the truth of a person, the good and the bad together, an emotional impact that cannot be achieved by simply speaking the kind words, the ones that everyone expects to hear. It was an impact I did not realise I would appreciate quite so much, but I felt it all the way down to my bones as I read it. It hurt, and it helped, to have a story reminding me that we can have complex feelings for our dead, in a time when I needed just that. From a personal perspective, I might even say this is the best of the stories in the series, simply because it has hit me so intimately in my own unsettled emotions.

But even if I step outside this personal impact, it's a story whose themes are bittersweet and beautifully crafted. As well as those of death and mourning and the memories of a person left behind - themes made all the more poignant in a setting full of characters whose entire purpose is their perfect recall - it is also a story of how people change, how parting and returning may bring you back to a different person than the one you left behind. And that in discovering that, you realise you too are different from the person who left. All the Singing Hills books are deeply, inexorably rooted in people and their relationships, but Mammoths at the Gates doubly so. We follow Chih, our cleric protagonist, as they return to the Singing Hills Abbey after their travels, hoping to see again their neixin companion who returned before them, as well as their familiar fellow clerics and old tutors. But they find their best friend suddenly serious and grown up, their neixin now a mother of a fledgling, and much of the abbey gone to a nearby situation that requires their attention. Their home is almost empty, and they have to reckon with the changes against the backdrop of a very present threat - the eponymous mammoths at the gate - whose title drop within a few pages of the opening of the story I particularly appreciated.

But like all the other stories, it isn't really a story about Chih, no matter that we continue to learn about (and love) them through how they approach the stories of other people. And it is no different here - we learn about Chih through how they cope with the changes they bear witness to in their erstwhile best friend, and the stories they hear and react to during the funeral. They are the conduit through which we receive the stories, and like any good medium, they bring with them their own personality to the message. For only novellas, for stories that always spotlight other people, Nghi Vo has done an amazing job of giving us such an insight to the person on the fringes of all those stories, a wry, cheerful, thoughtful, ever so slightly rebellious but ultimately dedicated cleric, one who truly yearns to hear what people tell them, and believes in their duty to keep those stories safe, because the things that happen to the people in their world, even the little things, ultimately matter.

We likewise get those tantalising little glimpses into the world, and as in all the books, we continue to dwell particularly on food. In a book about homecoming and comfort, it feels all the more important to have that there, all the more true to life. Cleric Chih has always been quick to describe what they eat - or want to eat - in all the novellas, and so getting back to the green onion buns, the rice and mustard greens, the salted plums of their home, the things that comfort them against the world, makes you yearn for those foods too, even if you've never tried them yourself. Because they're not described in the way food sometimes is, as vivid sensory experiences, full of taste and smell and almost sensual aesthetics. Instead, food reverts to its emotional self - rice as a balm for the soul, a green onion bun or milk candies as nostalgia, a salted plum as a rare treat. We understand food, as we understand much of the story, through the lens of Chih's experience. Whether or not I would like salted plums, here, they are likeable, and that positioning in the story is, for the moment, more important than my own imaginings of what a salted plum might taste like.

If I were to be fanciful, I might say that all the Singing Hills books are a thesis on the importance of bias for the narrator in a story. Because they would not be what they are - which is wonderful - if they weren't constantly coloured by the perspective from which we see them. Whether it is Chih and their experiences, or the framing devices that shift from book to book, each of these stories is as much the medium as the message, the two woven so thoroughly together that extraction would make each meaningless except as part of the whole. And Mammoths at the Gates is no different in that.

But likewise, for me, it is also now inextricable from my own experiences, and my own bias. I cannot but view it through the lens of my own mourning, I cannot but find myself in the story, and be comforted. I declined to speak at my grandmother's funeral, and ultimately, so does Chih decline to speak at their mentor's. I find a form of fellowship in that; I feel seen. And it is a testament to how well the story is told that such resonance is so easy to grasp, and so poignant.

*On twitter, we quite frequently speak ill of the terrible dead, but twitter is its own little microcosm, and I don't want to use it as a pattern for society at large. God no.

--

The Math

Highlights: A continued dedication to great framing devices, emotional resonance so substantial you could make buns out of it, bittersweet friendship

Nerd Coefficient: 10/10

Reference: Nghi Vo, Mammoths at the Gates, [Tordotcom, 2023]

POSTED BY: Roseanna Pendlebury, the humble servant of a very loud cat. @chloroform_tea