Sometimes what works in one medium doesn't translate well

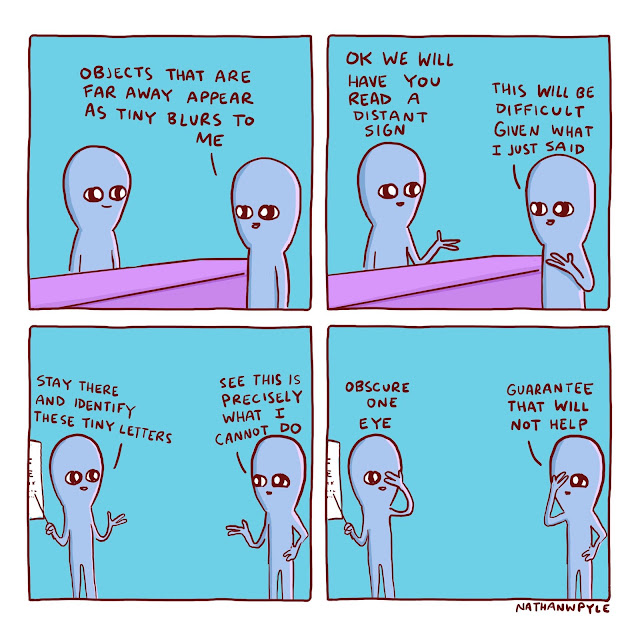

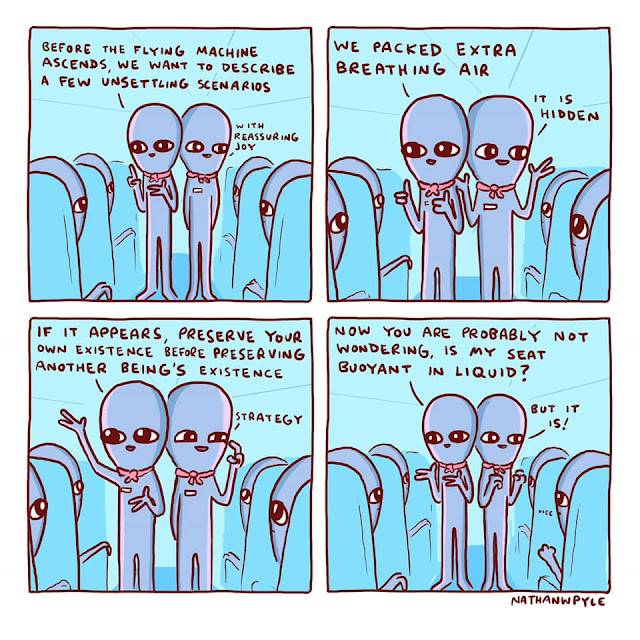

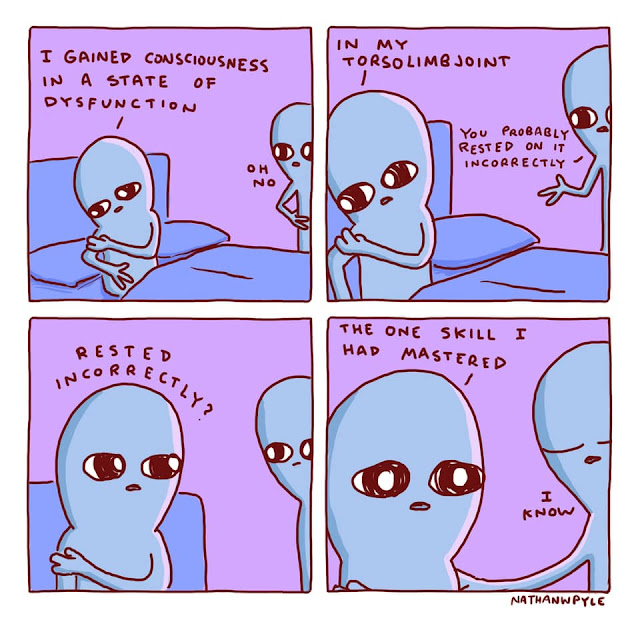

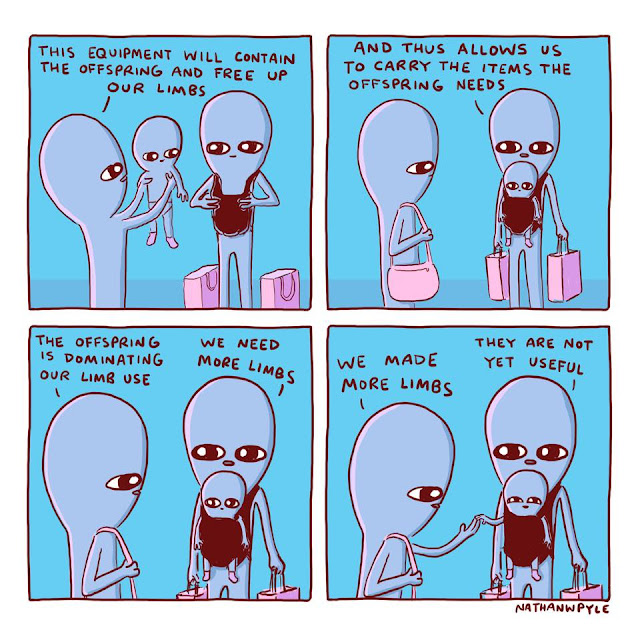

With the webcomic Strange Planet, first published on Instagram and then in book format, cartoonist Nathan W. Pyle has become the rare success story where a comedian has proved able to sustain a career based on knowing exactly one joke. His featureless blue aliens lead entirely ordinary lives, doing the same things humans do, but speaking with a degree of technical precision that exposes how abnormal our assumptions of normality truly are. Pyle has discovered how to milk the same gimmick a million times, creating a surprisingly caustic style of humor clothed in pastel. From innocent slice-of-life scenarios, Strange Planet can go into some really dark insights, a remarkable feat of tonal balancing without which it wouldn't have become so explosively popular.

This year, Strange Planet has been adapted into an AppleTV+ series, and the translation from comic strips to animated episodes has not done it any favors. The first shock to the viewer is the selection of voices for the blue aliens. A crucial ingredient in the Strange Planet recipe of humor is the distancing effect of watching nonhumans perform and judge human actions. They look alien, and when you read the comic, they (presumably) sound alien in your head. But the animated series gives them normal human voices (sometimes too normal), which deflates a huge part of the punch of the jokes.

Another self-sabotaging choice is to eschew the comic's tried-and-true observational style of comedy and adopt instead a blandly wholesome, almost didactic tone, with every episode imparting a life lesson of profound significance to the characters, who never have worries beyond those of comfortable middle-class urbanites. The only dramatic ingredient that opposes their desires is their own limited perspective. This is not a self-contained environment like Sesame Street; this is presented as an entire society in all its complexity, yet no one harbors any malice, no one is hostile, no one knows hate. Strange Planet uses the aesthetic presentation of a children's show to speak to an adult audience. Imagine the world of The Invention of Lying populated entirely by clones of Mr. Rogers.

In these confusing times of meta-post-irony, more sincerity is always welcome, but this series has zero subtext. There's nothing to interpret. If you've ever read a writing guide warning you to not make your characters always spell out what they're feeling, Strange Planet is the demonstration of why that advice exists. By tuning the characters' emotional openness up to eleven, Strange Planet (the show) loses the ironic spice that makes Strange Planet (the webcomic) unique. Since the moment he posted his first blue alien jokes in 2019, what Pyle has been doing, intentionally or not, is to gradually codify a highly specialized language that only makes full sense when parsed in contrast with the readers' ordinary language. When his comic calls a suntan "star damage," it is funny because, in order to decode that unusual phrasing, we're forced to acknowledge an inconsistency in our own preferences. But when the animated series presents an entire civilization that routinely calls a suntan "star damage" as an accepted fact of life, the joke lands dead on arrival.

This happens because, in the adaptation, the language is no longer the joke. The characters have gained backstories and motivations beyond the snippets we get in the comic. With those extra layers of dimensionality, the peculiar way they speak becomes the least interesting thing about them. Now they have jobs, and neighbors, and chores, and marriages. They're no longer generic abstractions of the human experience; now they're particular individuals.

It's a substantial change, but it's a requirement of the television medium; the alternative, if a more faithful adaptation had been the goal, was to plan each episode as a half-hour anthology of sketches, and that would have quickly gotten tiresome for both the writers and the viewers. The aliens' function in the story is no longer that of cerebral overanalyzers of human activities; now their function is to be relatable stand-ins for the viewers. The Strange Planet comic strips work best when we're supposed to laugh at the blue aliens. The problem with the show is that it wants us to laugh with them. They have difficulties! They're just like us! And that's what ruins the joke.

Once the blue aliens are full characters with plot arcs, the viewers form certain expectations of resolution, and the show commits yet another mistake on that front: every single episode has exactly the same emotional journey. Plot A and Plot B are so prominently delineated that they become a predictable element of the show, distracting from whichever of the two is being told at the moment. In both plots, someone is struggling with a source of anxiety, they explore why their usual coping strategies don't work, they gain an unexpected insight from a different angle, and they go on with their lives with no further conflict. What tries to be a sweet character beat comes off as reheated melodrama; what is intended as a life-changing realization feels like a Hallmark Channel platitude.

I'm not saying that it's pointless to attempt to make comforting comedy; at least it's not always artistically pointless, and it's definitely never ethically pointless. This decade has been kicking us with punishment after punishment; no wonder the mood of this generation is a state of perpetual exhaustion. One notable response of today's art to a world that is crumbling down is to give us a breather, to serve us hot cocoa and cookies, because life is just too much. And Instagram webcomics have risen to the occasion; just look at the pure gentleness in Mrs. Frollein, Dinosaur Couch, Wawawiwa, or Sarah Andersen. But Pyle overestimated how compatible his creation would be with a cozycore aesthetic, and how much adult viewers needed to hear the most condescendingly basic pop psychology advice.

Nerd Coefficient: 5/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.