A disappointing love letter to an evocative craft

When you think of cartography and fantasy books, you typically imagine quests, crinkled vellum for the discerning adventurer, or crumbling parchment for the more impecunious; maps showing forgotten paths leading dragons or treasure (or both), discovered at the bottom of an old chest, or perhaps purchased from a stall in the market square that is gone when you go back to ask questions.

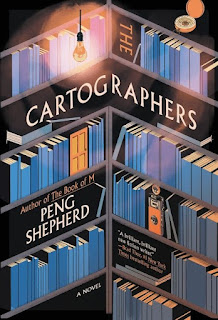

The Cartographers takes that sense of magic and updates it to two time periods: the slightly retro 1980s and modern day. No longer are maps made of sheepskin and penned with quills and iron gall ink. Instead we have folding highway road maps and big tech GPS systems. Yet these mundane types of maps are not without their magic, and Peng Shepherd does an admirable job identifying the perfect conceit for a fantasy tale about cartography. Specifically, she builds on a strategy that mapmakers use, in which they booby-trap their maps, adding in fake places that don’t exist so they can catch rival publishers who copy their work rather than doing their own surveys and drafting.

The story focuses on Nell, an academic, a historian of old maps, who was ejected from her dream job at the New York Public Library, fired by none other than her own father, for a quarrel she refers to as the Junk Box Incident, and is coy about elaborating on for longer than she needs to be. For seven years she has chafed over why this argument had to turn into such a catastrophic quarrel, and has been alienated from her father and her former colleagues ever since.

Then one day her father dies at his desk at the NYPL, and when Nell comes to help the police in their inquiry, she discovers an old highway map in his desk drawer. She recognizes it as one of the maps from the box of maybe-fakes that had precipitated her downfall, but it’s not one of the fabulously valuable-if-real ones; it’s an old highway road map. Worthless. But when Nell, in an act of tribute to her father, decides to catalogue it in the inter-institutional map-cataloguing system, it turns out that all of the other hundreds of copies of this map are missing, stolen, or destroyed somehow. And the day after she catalogues it, someone breaks into the NYPL but doesn’t steal anything. She researches it further, and finds odd message threads on internet forums warn people not to ask too many questions or else The Cartographers will come looking for them.

This is a terrific opening. I was all on board with this book after I got this far in the set-up: a thirty-something female protagonist who has earned her expertise through an actually realistic educational pathway (none of this three PhDs by the time she was 25 nonsense); a niche interest that the author clearly understands at a deep level, down to the typical workflow used for the cataloguing software interface; a deep and abiding love for the New York Public Library that comes through every fond description of the framed pictures on the wall and the décor of the study rooms. And an intriguing mystery, to boot. This is great! I thought.

But as events unfolded, bits of the story began to rankle. One bit revolves around a big-tech job at a company like Google or Amazon, called Haberson Corporation. Haberson is huge. Its search function has become a verb: ‘Have you Habed it?’ And its goal is to build the perfect map. Here’s how it’s described, from the perspective of one of the programmers:

[Haberson’s Map algorithm] would be not just unfathomably gigantic, but also graceful, each piece of information so well integrated into the whole that the map would be like music. A symphony. A geographical program capable of containing in one massive depiction every singlestream of data from every single arm of the company. Haberson Global had medical consultancies, urban planning teams, mass transit tracking, interior design apps, weather charts, internet search programs, social media, food and grocery delivery, sleep monitoring, flower bloom patterns, endangered species migration routes—all of it would feed into the map, more information from more sources than ever possible before, through the algorithm Felix’s team was designing. .. A refined code that would, somehow, take the Haberson Map from incredible to perfect.

First of all, I have enormous difficulty believing that engineers and tech people—not the CEOs but the actual programmers—really believe than an algorithm can be made ‘perfect’ (what does that even mean? Perfect for what?). My impression is that most people who actually write the code have more of the following perspective:

|

| https://xkcd.com/2347/ |

Likewise, the CEO of Haberson is unrealistically perfect. He always responds to emails from his employees personally (personally? From tens of thousands?), and he’s dedicated purely to the goal of perfecting the Haberson map. He sounds like he is intended to be in actuality how a rather disagreeable subset of the internet believes Elon Musk to be in their heads. And, living as I do in a world of actual Elon Musks, it’s hard to believe in big tech CEOs with that kind of integrity. My suspension of disbelief is pretty stretchy, but it can only flex so far. (Haberson turns out to have his own hidden depths, but they both take an awful long time to be revealed, leaving me rolling my eyes at Haberson’s purity, and were also desperately obvious well before they were revealed, leaving me rolling my eyes when I was expected to gasp at something I’d figured out fifty pages ago.)

The structure of the revelation of the secrets behind this road map also irritated me. A lot of the narrative is told from the perspective of people Nell tracks down, people who knew her parents in the 1980s, and whose contributions are recounted in flashback chapters. This sort of thing works well if each person knows a little bit of the puzzle, and only by tracking them all down and making each of them tell what they know can Nell figure out the whole story. But in this book, every person Nell tracks down is actually in a position to tell her everything, so their constant breaking off and holding back serves no real purpose beyond to irritate the reader. And what they do tell her is full of literary exposition and characterization and introspection and philosophical meditation that works well as a chapter in a novel, but is entirely unbelievable as a narrative from the mouth of someone who both begins and ends the conversation begging Nell to stop asking questions.

The narrative itself is also irritating in what it reveals. I won’t spoil the story, but I will say that it involves a group of new PhD students making some very dumb choices and getting into a heap of trouble that was entirely of their own making. It has more than a bit of Secret Histories to it, but what is forgivable (or at least artistically defensible) in a group of college kids who fancy themselves extremely clever is much more tiresome when the people are in their late 20s and have PhDs and should really know better. Yes, there is a wonderful kernel of magic at the core of it, but all of the interpersonal drama surrounding that kernel badly dragged down the story.

Against this perpetual irritation raised by the larger structural issues, I was in no mood to forgive smaller errors. A big project being planned in the mid 1980s is going to synthesize fantasy maps from Middle Earth, Narnia, Earthsea, and . . . Discworld? I stopped there and looked up publication dates. The Color of Magic, the first Discworld book, was published in 1983. The Light Fantastic came out in 1986. This flashback sequence is taking place in maybe 1985 or so. Discworld simply wasn’t enough of a thing yet to rank with Middle Earth and Narnia.

Then there is a horribly inaccurate bit about fountain pens, laughably bad, hilariously bad for people who know the difference between a cartridge filler and a piston filler;* and at the end someone gets a very important job that they are desperately unprepared for, on the basis of qualifications that are over a quarter century out of date.

All together, the bits that I’ve highlighted as irritating me are not in themselves all that bad. But they add up, and the end result is a disappointment. The conceit of this book was superb; the execution needed work.

—

Highlights

Nerd coefficient: 6, enjoyable, but the flaws are hard to ignore

• Deep and abiding love for cartography and the NYPL

• Poorly constructed flashbacks

• People who should really know better being the authors of their own downfall

• Unconvincingly virtuous tech billionaires

CLARA COHEN lives in Scotland in a creaky old building with pipes for gas lighting still lurking under her floorboards. She is an experimental linguist by profession, and calligrapher and Islamic geometric artist by vocation. During figure skating season she does blather on a bit about figure skating. She is on mastodon at wandering.shop/@ergative

Reference: Shepherd, Peng. The Cartographers, [William Morrow, 2022].