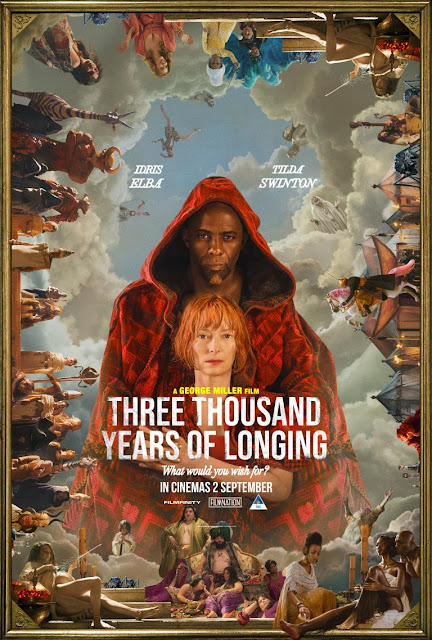

This perfectly executed visual feast disentangles the ties between desire, renunciation, the vertigo of choice, and the need to feel desired

When one encounters an impeccably beautiful work of art, the attempt to explain it feels like a desecration. Three Thousand Years of Longing is that kind of art that you're meant to experience more than understand. It does follow a plot, and the plot does make arguments, but to dissect those arguments risks losing sight of the experience. I can't properly communicate to you the emotional content of this story. What I can try to do is describe what happens in it, but I will fall short of conveying all it says. This is one of those films that leave you permanently changed, and the only way for that secret alchemy to happen is to go yourself to the theater and let it wash over you.

Our protagonist is Alithea, a proudly independent divorcée with no time for personal attachments, who one day stumbles upon a genie in a bottle and is offered the proverbial three wishes. This genie has spent far too long inside the bottle and is desperate for a human to make up their mind and request the full set of wishes. To his dismay, he's put before a challenge no genie has had to face before: Alithea is a literary scholar, versed in all the tropes used in genie tales. She knows that every wish comes with strings attached. Unfazed, the genie insists there must be something she wants more than anything in the world. But after a lifetime of consuming classic literature, she has every reason to reject the deal, and none to trust that the genie is being sincere.

How do they resolve this clash of interests? They tell each other stories.

There have been thousands of stories-about-stories, but this one makes

the case that the ordinary act of desire is already an authorial move, a

transmutation of the human will into an arbiter of the universe. Who do

we think we are, to want reality to be different? But then again, what

can we do in this life but want? It's not fantasy to agonize over which life we ought to wish for; it's the common business of day-to-day choices. If genie tales are an allegory of anything, it's of the inevitability of consequences. No matter which path we take, we'll find something unexpected, sometimes unwanted. That's not a curse; that's life. At first, Alithea doesn't understand that. When presented with the inescapable need to choose, she applies the wrong set of rules by trying to metagame her life. What at first resembles a typical wish-fulfillment story becomes a self-reflective exercise where Alithea tries to ascertain what

type of story she's in, what the rules are, and therefore what endings are

available to her. This is why it's so important for the movie to focus on the theme of wishes: they are the mechanism by which human beings steer their story.

However, as I've said many times in this blog, life is not a story. Alithea's clever attempt at metagame is headed nowhere, because it's pointless to live on the assumption that events are headed toward a clear ending, because we're always situated in the middle of events, and it's not given to us to know how many pages are left. The genie presents Alithea with a similar warning: she can't expect the literary conventions of genie tales to apply to her, because what happens to her is shaped by her decisions. In spite of the fact that life is not a story, each one of us is still, in some manner, the author. We don't walk along the lines of established tropes. We write life every time we act upon our wishes. The key is to be aware that there's no plot, and we can't see the ending from where we stand. As if to make us conscious of that limited perspective, the film gives several times the impression that it's ended, only to fade back in with yet more story to tell.

For a story about stories, this one is quite unconventional. It dances from one genre to another, and joyfully refuses to fit the three-act structure we're used to look for in the Western narrative tradition. The only contemporary film that is remotely comparable to Three Thousand Years of Longing is the fantastic Everything Everywhere All at Once, which succeds at the impossible narrative feat of playing with all genres, all tones, all styles and all modes of stories to encapsulate the elusive human experience of lamenting the road not taken. Three Thousand Years of Longing also uses a multitude of stories to express a complex truth from various angles, and the truth at the core of this story is that it's worthwhile to choose love, even if it's terrifying, even if we don't know how it will end, even if it exposes our vulnerable side, even if it demands we bet everything on it. The genie explains the rules of the game: you can't wish for eternal life, or resurrection, or world peace. That makes the stakes relatable to the rest of us: if we must be mortal, and we must be in this world as it is, what form of happiness is still possible?

Before we even watch the first scene, Alithea warns us in voiceover that, even though this story contains truth, it is disguised in symbols. So what's beneath the colorful parade that dazzles the eyes in this film? This is, of course, a love story, but it takes a long time to admit it is one. Without the trappings of fantasy, it's about a lonely woman who on a trip abroad meets a tall, dark, handsome stranger but dreads the uncertainty of opening her heart again. If we read this film as a love story, we can notice some familiar behavioral patterns. The genie needs someone to need him, which is the textbook definition of codependency, while Alithea pretends she needs nothing, which in interpersonal psychology is called a dismissive-avoidant attachment style. Put them together, and you obtain the frustrating mishaps that fill 95% of romantic comedies. This film wants to do something more mature than that. Both lovers must relinquish their flawed coping strategies before they can love wholeheartedly.

After the film presents this idea, all the other pieces fall into place. If you can be granted any wish, what happens if the target of your wish is a person? One could call that love. But to be complete, love cannot work like possession. I can wish for a new hat, and then I own that hat. Not so with a person. Owning someone is contrary to love. And here is where the master/genie dynamic becomes key to the story. When you love someone, you trust them to satisfy your needs, which is akin to the relationship we would have with a genie, except that the genie is magically forced to obey you. Your lover is only bound by their own love for you, which means that you fall under that same expectation. Preferably not to the degree that a genie is magically bound to; it's

not healthy to go to the other extreme and forfeit your existence if you're not needed. That strange balance is what makes love, and I mean truly honest love between equals, look so daunting from the outside. No less than what you ask will be asked of you; no more than what you offer will be offered to you. You can't compel your lover's services, not without killing the love, but the love you feel compels you to serve.

And it's a joyful servitude we happily accept, isn't it? To exist for someone, to satisfy their every wish. But it's a servitude that can only be given, never demanded. That's the final lesson Alithea learns: she wants to be loved by a genie, and he's happy to be a genie to her, but she can't treat him like a genie, because that means killing the love. To use the rules of magic to command him to love her is to negate any truth there could have been in his love. She believes the genie will hide strings attached to anything he grants, but actually it's she who has strings attached to the act of asking. It's a tricky conundrum, and it's the human tragedy explored in each flashback told by the genie. We must be careful with what we wish for, because our wants can easily morph into demands, and love cannot survive under duress. It can't be love if you treat your beloved like a genie. Instead, we must risk the very real chance that our beloved may refuse our wish. We must risk the pain of abandonment. Some reject that risk, and stay preemptively abandoned. But if we each take that blind leap, if we mutually voice our heart's desire without making it into a requirement, then magic can happen.

Nerd Coefficient: 10/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.