Pinocchio is the perfect story to illustrate this felicitous contrast between the soulless and the alive, the feigned and the sincere, the automatic and the intentional

Cultural critic Walter Benjamin would have had a field day studying Disney's remake binge. In his immensely influential essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he wrote about the way mass industrial techniques have modified the social function of art and made it depend on a new set of assumptions: whereas unique creations used to be made to be appreciated personally in a fixed location, and their value resided in existing precisely where they did, infinitely repeatable copies are made to be exhibited to everyone, and their value resides in being readily accessible anywhere.

Let me try to give a more vivid description of Benjamin's argument: It is a materially different experience to buy a plane ticket, land in Saint Petersburg, take a cab to the Hermitage Museum, walk to the collection of Italian Sculpture of the 15th-20th-Centuries, and stand before Pietro Ceccardo Staggi's marble sculpture Pygmalion and Galatea, versus typing the museum's URL on your browser and searching for a digital image of the same statue. In both scenarios you're experiencing the same geometrical shapes, colors, proportions and subject matter. If you had the real statue in front of you, you wouldn't be allowed to touch it anyway, so what's the difference between both modes of seeing? The difference is what Benjamin called the "aura" of the work of art. When you go to the trouble of visiting the real statue, you experience it on its terms, not yours. In Benjamin's words, there is no replica of presence. Whether we want it or not, we endow the original object with a set of cultural meanings that the most faithful copy doesn't remotely deserve.

(To be fair, this whole discussion relies on Western categories of art theory. Eastern art uses completely different notions of authorship, authenticity and reproduction.)

By sheer chance, acclaimed Mexican director Guillermo del Toro has just released on Netflix his personal artistic take on the tale of Pinocchio almost at the same time as Disney+ launched… whatever their remake is trying to be. We have here an opportunity to analyze the process of copying, remaking, recreating, and reimagining. The fact that this story happens to be about an imitation of humanity that ends up reclaiming an authentic humanity is the marvelous cherry on top.

Let's go back to Staggi's statue Pygmalion and Galatea for a moment. This sculpture represents simultaneously a culmination and a transgression of the act of representing. The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea is about an artist who creates a copy of the human shape, only for the copy to miraculously become alive. This motif of the representation that assumes the reality of the thing represented has permeated literature from Adam, the man made of earth, to Frankenstein's creature, the man made of men. It's important to keep this symbolic tradition in mind before engaging in a discussion about Pinocchio (the puppet that represents a child), Pinocchio (the Disney movie that represents the puppet), Pinocchio (the Disney movie that repeats the Disney movie) and "Pinocchio" (the literary archetype that has been copied so many times in speculative fiction).

What allows this analysis to move fluidly into and out of the diegetic level is the fact that not only is Pinocchio the movie a work of art; Pinocchio the character himself is also a work of art, an exceptionally precious work of art that thinks and speaks and thus can be asked directly about its meaning. Notably, Disney's new Pinocchio aspires to occupy obediently the position of Gepetto's dead son, while Netflix's Pinocchio embarks on an epic battle for his dignity and autonomy.

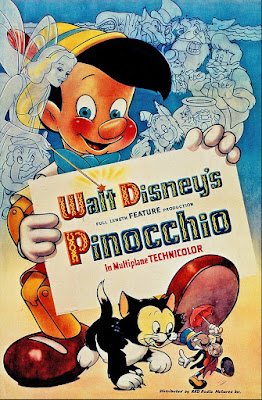

It's no coincidence that, being a puppet, Pinocchio's most common job in all adaptations is as an actor, a living representation of an imagined person. Nor is it a coincidence that Pinocchio's defining character flaw is lying, that is, the misrepresentation of reality. Pinocchio is a walking and talking lie that fools no one, a nonhuman entity that mimics humanity. While the 1940 animated movie is one of Disney's most beloved productions, the 2022 remake is, just like its protagonist, a lifeless thing, born of hubris instead of love, made only to evoke the nostalgic memory of an unrepeatable original.

If this remake didn't exist, Del Toro's Pinocchio would still be a masterpiece. But in the context of a media landscape where both versions can be watched in the same season, a big part of the discussion shifts toward how evidently and indisputably inferior Disney's remake is. It follows the 1940 movie so faithfully that it has nothing of its own to say on its topic. Its reason for existing is not to communicate an artist's inner being, but to add to a list of collectible trinkets. Gus Van Sant's widely ridiculed recreation of Psycho is a more interesting and thought-provoking cultural artifact than Disney's automated self-cannibalization.

One of the most salient ways one can begin to perceive the differences between all these Pinocchio adaptations is by paying attention at the way their respective names are marketed. The 1940 version was Walt Disney (the human being)'s Pinocchio. The 2022 remake is Walt Disney (the company)'s Pinocchio. On the Netflix catalog, Del Toro's version is explicitly named Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio. These naming choices are the first indication of the fundamental difference that exists between art created with an unmistakable human touch and art created by corporate mandate.

What makes the human touch special isn't even its uniqueness; it's enough that it has intentionality. Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a short story called Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, where he proposes that a different writer, in a different era, who spontaneously produced a text perfectly identical to Don Quixote would nonetheless be producing a different piece of art, because the context of creation and the context of reception are factors in the production of meaning. So let's look at the context of 2022. Disney's remake of Pinocchio comes to light in the nascent era of art produced by algorithm, the extreme state of the removal of the human subject from the process of artistic expression. This impersonal form of creation works by butchering thousands of previous creations into tiny pieces and recombining the parts into unexpected and not always logical compositions. It has an air of necromancy to ask a bot to cook up a realistic photograph of Napoleon shaking hands with Bugs Bunny in the style of Picasso's Blue Period. It's a recipe made of dead ingredients, all flavor and no substance.

This is also the era of blockchain art, art that doesn't exist to be enjoyed but to be traded. It's the era of hideous bored apes that don't demand appreciation for themselves but for their owner. It's the type of art that is only capable of expressing the amount of money it cost to acquire it.

Art with an impersonal motive is not a new threat. Italian educator Maria Montessori thought that children develop best when the learning environment accomodates their interests and capabilities. This is the complete opposite of the pedagogical method that prevailed in her time, a hyperpatriotic militarism that was more interested in making soldiers than citizens. Montessori denounced Mussolini's government for wanting to shape Italian youths by what she called "brutal molds." The choice of wording is polysemic: a mold is a tool of artistic creation, but also a tool of the industrial assembly line. The fascist project was to craft a nation of identical copies of an idealized man, representations instead of authentic subjects. Benjamin's essay criticized the mechanical copying of art, but Mussolini had already envisioned the mechanical copying of the human being.

This is what makes it so fascinating that Del Toro's Pinocchio is set during World War II. Fascism needs puppets, but Pinocchio is a puppet without strings, a free soul that cannot be controlled. He resists the reduction of his right to exist to his utility to the state; rebels against the corruption of his art by fascist propaganda; and ultimately rejects the us/them mentality at the root of every war. In his last heroic act, by willingly accepting human mortality, he emerges victorious over the worst of fascist horrors: a life where each individual death is trivial.

It's especially significant that this Pinocchio adds a subplot about a youth military camp exactly at the point in the story where a more conventional adaptation would insert the trip to Pleasure Island. In Pleasure Island, the most disobedient children lose all control and end up losing their humanity. This version of the tale inverts the moral message: here the most obedient children are controlled to the point that they lose their humanity. Where the original Pinocchio was a simple moralist fable about the dangers of rebellion, this adaptation is a more mature argument for the need of rebellion. This is the type of daring resignification that art needs from time to time to stay relevant, and that Disney would never dare try with its sacrosanct classics.

In his Pinocchio, Del Toro creates a child that would have made Montessori proud. He's innocent, literally born yesterday, but he meets the world with an undefeatable enthusiasm, with a sincere awe for the gift of being alive, and that spark of pure joy keeps burning under the cruelest circumstances. In contrast, Disney's remake gives us a Pinocchio without an identity, a nondescript tabula rasa waiting to be given a role to play. In the Disney movie, he's never his own person, following the brutal mold of brand integration to the point of doing a three-point superhero landing that should win a Golden Raspberry for cringe. In the Netflix movie, his first interaction with society is to question why an immobile statue of Jesus (another miraculous son of a carpenter) gets more respect than the living and breathing child he obviously is.

This is a Pinocchio (and a Pinocchio) with a beating heart. It's not afraid to show us the degree of despair that pushed Gepetto to the absurd task of building an artificial child, a fantastically shot scene that hits with the emotional punches of Astro Boy and Frankenstein. No portion of this suffering is hidden from the audience. There's nothing wrong with admitting that grief is painful, and war is painful, and loneliness is painful, and life is painful. The raw honesty with which the movie begins earns it an amount of goodwill that outweighs the artificiality of its medium. Over on the Disney side, Gepetto quickly forgets about his dead son by saying, "No more of these sad thoughts, huh? Time for some happiness," a quintessentially Disney attitude if ever I heard one.

Remember Pygmalion and Galatea? I neglected to mention one detail. The statue shown in the Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg is not an original. It's based on the earlier sculpture on the same topic made by Étienne Maurice Falconet and currently kept at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. But the version in Saint Petersburg is available for public viewing, while the one in Baltimore is (as of today) not. If you visit the website of the Hermitage Museum and search for Pygmalion and Galatea, you'll be seeing an image (the photograph) of an image (the statue) of an image (the earlier statue) of an image (the written myth) of an image (Galatea the statue) of an image (an idealized woman). And yet, the photograph still manages to convey the same sentiment of fascination and devotion as the first recitation of the myth centuries ago.

Guillermo del Toro has created a 21st-century classic, a Pinocchio imbued with a distinct artistic vision, a moral standpoint, a visual language of its own, a fully-developed protagonist, a complete worldview. The Walt Disney Company has created a souvenir shop copy of a revered classic, an item in an accounting spreadsheet, a cynical act of nostalgia bait with less moving power than a sixth-hand reproduction of someone who never lived.

Nerd Coefficient: 3/10 and 9/10. I hope I don't need to clarify which is which.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.