This industrial fantasy tackles how to overthrow corporations while protecting friends and family, all while dripping in vivid prose.

Marney is born into revolution because she’s lustertouched. Her family works for Yann Chauncey in his ichorite mines and production centers. Because she has spent her childhood around the stuff, she can control it, though it sends her into a “fit.” Due to the lustertouched children and the working conditions, her family strikes at the production center, but the strike is broken—more than broken. Marney is the only survivor and runs away.

On the run, she meets Mors Brandegor the Rancid and her group of bandits that rob from the rich. Marney is immediately taken with the group and pledges to help them. Her ability to control ichorite has helped her out of a few scrapes, and she wins the bandits over when she is able to seal a door and help them escape—all because ichorite is being incorporated into more and more products as Chauncey’s industrial empire grows.

The bandits accept Marney into their group and take her to the Fingerbluffs, where she lives out the rest of her childhood before truly becoming a bandit and working toward her ultimate goal of killing Chauncey. The Fingerbluffs is the home of all the bandits that steal from the rich to redistribute their wealth. Everyone who lives there is rich and it means nothing. All eat, all are clothed, all are fed. The place is utopic even though hidden away in a world beholden to ichorite and war. Marney is awed by her first sighting: “Into the Fingerbluffs we rode, the gorgeous, heaving Fingerbluffs, whose dingy narrow mews peeled out from the brick streets and held children who played there in the darkness, chasing each other and shouting, twisting, braids floating behind them in deference to their speed, not working, not governed, unafraid.” This childhood is so different than Marney’s upbringing, but she discovers the Fingerbluffs can exist because the servants overthrew the baron, but did not let the rest of the world know. Instead, they plead his insanity and were able to keep the larger public away from the isolated area. From there, the bandits assist other revolutionaries like the hereafterists, who work toward a utopia that they know they will never see.

Marney grows and develops her skills as a bandit until the Fingerbluffs is at risk of discovery, and she must strike at Chauncey in order to save her new family. Aiding the Fingerbluffs also puts her one step closer to her ultimate goal of taking revenge against Chauncey and destroying his ichorite-fueled empire.

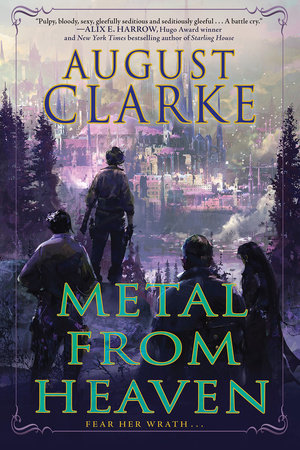

At its heart, this novel is a revenge story, but clarke is able to pack a surprising amount of worldbuilding into this very character-focused novel. The first person point of view of Marney is dense—a few steps removed from stream of consciousness. This closeness of the character makes the politics easier to weave into the fantasy. Marney is not radicalized by ideas but by her trauma and the physical impacts of being lustertouched. This impact changes how she sees the world, and when she uses her ability to control ichorite, the world turns shimmery, almost like an oil-slick (and reminiscent of the gorgeous purple-toned cover art by Richard Anderson). Like the best fantasy, clarke doesn’t give the reader an easy one-to-one for ichorite. It’s perhaps closest to oil but the mining process and physical impacts on the people bring to mind the coal mining (and strikes) of the 1900s. Because ichorite isn’t a one-to-one allegory, the novel has more depth. Like C. S. Lewis argues of the best fantasy, it isn’t a metaphor for our usage of fossil fuels but certainly comments on real world industrialization through Marney’s struggle.

While the revenge plot pulls the reader through the pages, the most captivating part of the book for me was the worldbuilding, particularly around the Fingerbluffs. The first time Marney rides into the Fingerbluffs on a lurcher (close to a motorcycle), it felt like the first time reading about Le Guin’s anarchist utopia Anarres. The sense of home that Marney finds there as a child and teenager comes through strongly due to the close point of view and draws in the reader. But the Fingerbluffs is only one portion of the worldbuilding. clarke gives the reader a rich world outside of that, with different cultures, religions, approaches to sex and gender, and so on. The world clarke creates is big enough for a trilogy, let alone this standalone book and left me wanting more in the best way possible.

What sets this novel apart from other bandit or heist books is the careful approach to gender. Unsurprisingly, the people of the Fingerbluffs are pretty queer-normative, but much of the world isn’t. There are still slurs, religious abstinence, forced heteronormativity, but also cultures where multiple genders exist and are determined by sex acts. Sex and gender aren’t simplified into utopic relationships among the bandits and and hate crimes among everyone else, but there’s a real nuance here to the depiction via the worldbuilding. This nuance is evidenced by clarke’s reading list included in the acknowledgements. I love when authors talk about their inspirations, and it was fun to see the wide ranging list that inspired clarke, including writers like José Esteban Muñoz, Leslie Feinberg, and Silvia Federici.

Metal from Heaven won’t be for everyone due to the density of the prose, but for readers looking for the found family of Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora or Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows or the politics of Le Guin’s best work, there’s so much to enjoy here. clarke manages to combine the fun and violence of a bandit seeking revenge with working class politics in this sexy, action-packed book. I know I’ll be thinking about the Fingerbluffs for a long time to come.

--

The Math

Nerd Coefficient: 9/10, very high quality/standout in its category

Reference: clarke, august, Metal from Heaven [Erewhon Books, 2024].

Posted by: Phoebe Wagner is an author, editor, and academic writing and living at the intersection of speculative fiction and climate change.