When Capitalism Produces Anti-Fascism: On Andor Translating Theory into Community Action

Note: This essay contains spoilers for season one of Andor. A spoiler-free review is available here.

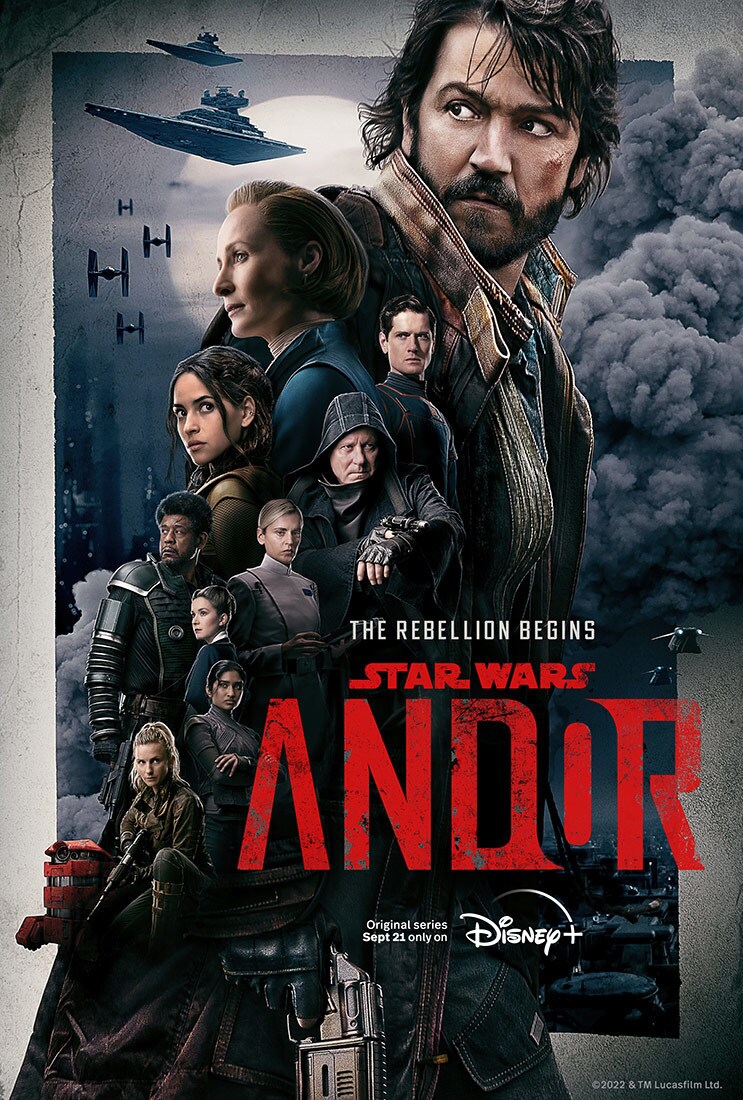

Speculative fiction writers have often been united in their call that more just futures must first be imagined in order to achieve those futures. Yet, these imagined futures are, by definition, speculative and often produced for the masses by major capitalist franchises and publishers. I argue that such stories are the ideal source to inspire community action. In 2022, the second biggest media company, Disney, produced a radical piece of anti-fascist storytelling: Andor. The twelve-episode first season follows Cassian Andor (played by Diego Luna) as he joins the rebellion. The radical potential of the Star Wars franchise has always come in fits and starts. While the costumes and borrowed language of WWII clearly emphasize the evils of fascism, the casual orientalism of the Jedi and the racist depictions throughout the franchise undermine the limited engagement with the concept of empire featured in the three trilogies. Andor showrunner Tony Gilroy addresses the Empire by depicting it as a war machine of extractive industry—and how communities mobilize against an entity so galactically large.

Disney has rarely been progressive in its storytelling, from the 1946 Song of the South to reluctance to show LGBTQIA+ content to pro-government propaganda throughout phase four of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. While there are certainly surprising moments, such as Ms. Marvel, the media company would not be considered leftist. Similarly, the Star Wars franchise pre-Disney acquisition made sweeping gestures that fascism was bad, but more nuanced takes were often buried deeper in the canonical novels or animated shows, which became noncanonical with the Disney acquisition. Additionally, the anti-fascist sentiments were often undermined by the orientalism, racism, and sexism throughout the first six movies. While the films’ messages were clear that the Empire was the villain, the Empire is also cool enough to be worn on T-shirts and tattooed on people. The franchising around Star Wars, as continued by Disney, is incongruous with any focused critique of anti-fascism or imperialism. Yet, the popularity of Star Wars makes the franchise an ideal vehicle to deeply engage with issues of imperialism and fascism because it has become cultural shorthand in the U.S.

While the plot of Star Wars cannot function without the Empire, their acts of colonization are often minimized as tragic backstories or trivialized, as with the Ewoks. Even one of the most shocking moments, the planetary destruction of Alderaan, is shorthand version of colonial violence that undermines the act. It repeats a common Western concept of apocalypse that people and cultures are erased in a singular moment, and, in a narrative sense, that such a moment is merely a plot point, an inciting incident. This depiction of instant erasure undermines not only the violence but the act of resistance against empire. As Nick Estes writes of Indigenous resistance against the U.S. empire: “Ancestors of Indigenous resistance didn’t merely fight against settler colonialism; they fought for Indigenous life and just relations with human and nonhuman relatives, and with the earth” (Kindle Loc 3858-3859). Even the monarchical Princess Leia does not seem to experience trauma over the loss of her home planet, but rather the focus remains on destroying the empire—not fighting for life. Indeed, for Alderaan, there is no life left to fight for as the white imperial fantasy is fully played out in A New Hope at the instantaneous destruction of entire peoples, cultures, and ecosystems.Andor presents the Empire as machine of colonialism through extractive industry. Over twelve episodes, Andor follows the titular Cassian Andor as he experiences colonization and is radicalized against the Empire. Cassian lives on Ferrix, an industrial planet, with his adopted, elderly mother Maarva (played by Fiona Shaw). Cassian is looking for his sister while making money selling contraband, and during a security shakedown, he ends up killing both officers. Desperate to make enough money to leave Ferrix, he sets up a meeting to sell a piece of Imperial space technology, which is how he meets Luthen Rael (played by Stellan Skarsgård), the current shadowy head of the nascent Rebellion. Luthen recruits Cassian for one job, which would make him enough money to escape Ferrix with his mother, Maarva. Cassian agrees to fly the escape ship after a rebel group steals from the Imperial payroll. While the heist is successful and Cassian escapes with his chunk of the money, he is captured and imprisoned for being in the wrong place at the wrong time in an industrial prison complex where the incarcerated people make parts for the Death Star. Meanwhile, Ferrix is occupied by Imperial forces due to the extra attention Cassian’s actions have brought. Cassian is further radicalized in prison and helps lead a revolt. He returns to Ferrix to help his community, and they rise up against the occupation.

In the first few episodes, Andor focuses on two communities resisting the Empire: the working-class people of Ferrix and Cassian’s home planet of Kenari. These opening episodes present a facet of the Empire that the Star Wars franchise often leaves to the viewer’s imagination: how is the Empire oppressing people? In episodes one and two, the fictional Empire is shown acting like an empire. In episode one, “Kassa,” Cassian Andor is shaken down by two security guards, outsourced by the Empire. The sequence of two white men in uniform threatening a brown man blends reality into the science-fictional space of Star Wars. The fallout of this moment is interspersed with flashbacks to Cassian’s childhood on Kenari, a planet stripped and mined by the Empire before the planet was abandoned due to an unnamed disaster. The extraction also seemed to have disrupted the Indigenous families of the area as only the children remain. Wide shots are reminiscent of images of mines in Venezuela or Appalachia. Rather than used as a playground for a lightsaber battle or using the Indigenous people for laughs as in The Phantom Menace (1999), the destruction is centered on Kassa, a child without any elders, who does his best to fight the Empire with what tools he and the other young people have created. As Kathryn Yusoff points out when discussing mining and colonialism: “While the search for geologic resources instigated the imperative to enslave, geology quickly established itself as an imperial science that both organized the extraction of the Americas and, in the continued context of Victorian colonialism, became a structuring priority in the colonial complex, especially in India, Canada, and Australia. These territories became organized as material resources and markets for Empire” (82-3). Thus, in the first episodes of Andor, the beginnings of the Star Wars Empire parallel imperial tactics used by the U.S. and the British empires. Even the plot points of Cassian searching for his sister he was separated from on Kenari by a well-meaning white woman parallels the U.S. separating Indigenous children from their families and the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement. These echoes of current environmental and social justice issues deepen the possible engagement with not just understanding Empire in a popular context, but also what it means to resist.

The violence of colonialism is also centered during the heist sequence as the Imperial airfield occupies a sacred site on the planet Aldhani. The Imperial settlers have slowly been displacing and replacing the Indigenous Dhanis population, and now just as many Imperial soldiers want to see the planet’s famed meteor shower as Indigenous people. The tactics of Empire once again blend with reality, as the Empire funds way stations along the path, using cheap alcohol as a way to disrupt the event: “It’s a ten-day trek up from the Lowlands. […] Along the way, we’ve placed a series of ‘Comfort Units,’ shelters and taverns with cheap local beverages” (“The Eye” 00:05:39). While there are more examples of colonial violence enacted on the Dhanis people over several episodes, this engagement demonstrates the actual workings of empire as reimagined in a space opera context. These two depictions of colonialism through extractive industry and military occupation turn the Empire into an actual imperial force.

Importantly, Andor doesn’t rely solely on critiquing empire but includes revolutionary theory. Throughout the show, the rebels aren’t slinging lasers but manifestos. Because the cultural shorthand of Star Wars is so prevalent in the U.S., backing the rebellion with leftist ideology creates opportunity to inspire the viewer. During the Aldhani heist, Cassian meets Karis Nemik (played by Alex Lawther), a young white radical writing a manifesto. While teaching Cassian how to use a piece of modular, nonnetworked star-charting technology, he explains how the empire creates knowledge systems: “We’ve grown reliant on Imperial tech, and we’ve made ourselves vulnerable. There’s a growing list of things we’ve known and forgotten, things they’ve pushed us to forget. Things like freedom” (“The Axe Forgets” 00:11:29). This rhetoric mirrors current thought around many countercultural acts: from homesteading to food foraging to the “right to repair” movement. An excerpt of Nemik’s manifesto is read aloud in the final episode: “Random acts of insurrection are occurring constantly throughout the galaxy. There are whole armies, battalions that have no idea that they’ve already enlisted in the cause. Remember that the frontier of the Rebellion is everywhere. And even the smallest act of insurrection pushes our lines forward” (“Rix Road” 00:14:25). These words play as a working-class town of mostly people of color prepare to face off against an occupying Imperial force that has already injured some of their people. While inspiringly vague, “random acts of insurrection” as an overwhelming force against a galactic Empire provides a framework for the viewer to do something, even if it seems small. It gives meaning to the protests that have erupted across the U.S. year after year, from Standing Rock and #NoDAPL, to the 2020 George Floyd protests, to the marches for the right to an abortion, to protect Trans rights, for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women—the list continues. Nemik’s manifesto ends on a simple call to action: “Remember this: Try” (“Rix Road” 00:14:52). In a clear rejection of Yoda’s famous line, Nemik’s manifesto recognizes that ending an Empire is not as simple as blowing up a single ship but requires ongoing acts of resistance to dismantle oppressive systems.

Nemik’s manifesto is not the only call to action. Throughout the show, Tony Gilroy utilizes monologues by talented actors Andy Serkis, Stellan Skarsgård, and Fiona Shaw at pivotal moments to inspire action. For example, Andy Serkis as Kino Loy motivates incarcerated people to participate in a prison escape. With abolitionist overtones, Loy reminds the incarcerated people: “We know they [killed] a hundred men on Level Two. We know that they are making up our sentences as we go along. We know that no one outside here knows what’s happening. And now we know, that when they say we are being released, we are being transferred to some other prison to go and die and that ends today” (“One Way Out” 00:27:26). While prison breakouts are a staple in science fiction, the Imperial Prison Complex connects incarceration with imperial rule. After the heist, Cassian successfully escapes with his share of the money. He’s caught and sentenced to prison not because of his connection to the heist or because he killed the security officers on Ferrix. Rather, Cassian was simply in the vicinity of a crime, looked “suspicious,” and was convicted to an extended sentence because the Empire had raised the sentencing limits to squash resistance. Again, the policing of people of color as a tactic of control blends reality with the science-fictional. With this incident as the set-up, the prison complex is already positioned to be critiqued as an arm of imperial control rather than any gesture at justice or rehabilitation. This critique is furthered when the viewer realizes the incarcerated people are being used to build parts of the Death Star, thus connecting the prison system with the ultimate tool of control in the Star Wars universe. The only possible response is a violent uprising where the incarcerated people work in solidarity to take over the facility and escape.

While these are only a handful of examples, what makes Andor a potentially powerful tool for disseminating ideas is that the show takes seriously the cultural impact of Star Wars and uses that impact—the nascent ideas of empire, rebellion, freedom—to critique, inspire, and demonstrate direct action. As an academic tool, Andor offers a cultural touchstone that can be used as a translating tool to connect less accessible ideas—empire, the panopticon, settler colonialism, extractive industries—with a story many in the U.S. think they know: Star Wars. Sylvia Wynter sees humans as hardwired for story, as evidenced in the Western world by the reliance on biblical and Darwinian origin stories, which have been disseminated by white colonizers. Wynter pulls from Frantz Fanon to propose a new description of humanity that acknowledges the human reliance on story, something that Wynter sees as unique to the species. McKittrick summarizes Wynter’s argument: “Our mythoi, our origin stories, are therefore always formulaically patterned so as to co-function with the endogenous neurochemical behavior regulatory system of our human brain. Humans are, then, a biomutationally evolved, hybrid species—storytellers who now storytellingly invent themselves as being purely biological” (11 italics in original). Following Wynter, if we recognize that humans are hardwired for storytelling and that Western thinkers have been using what Wynter’s argues is a biological imperative in order to narrativize certain ways of living (i.e., capitalism), then it is a wasted opportunity to ignore stories like Andor that stand in opposition to such origin narratives. In fact, neglecting these oppositional narratives may be what people in power would prefer. Talking about empire in the context of Star Wars might be easier to understand, help people be less defensive. It’s easy to say the Empire was wrong to displace the Dhanis in order to make an airfield for one of the most common symbols of the Empire: TIE fighters. Breaking down the tactics of imperialism through a science fiction show creates a different lens to understand the same actions in the context of U.S. imperialism. The universality or popular enjoyment of Star Wars shouldn’t be viewed as cheapening but rather as an ideal way to engage with people who might shut down at the word “colonialism” or “abolition.” Use Nemik’s manifesto to guide the inspired to other people who call for freedom: Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, June Jordan. Let Kino Loy’s call of “One way out!” inspire solidarity.

In the final episode, the working-class community of Ferrix clashes with the Imperial occupiers of their town during a funeral for Cassian’s adopted mother, Maarva. As part of the funeral, a holograph of Maarva plays in which she challenges the people of Ferrix: “We’ve been sleeping. […] We had each other and they left us alone. We kept the trade lane open, and they left us alone. We took their money and ignored them, we kept their engine churning, and the moment they pulled away, we forgot them. Because we had each other. We had Ferrix. But we were sleeping. I’ve been sleeping. And I’ve been turning away from the truth I wanted not to face. […] But I’ll tell you this, if I could do it again, I’d wake up early and be fighting those bastards from the start!” (“Rix Road” 00:36:18). In these final moments, this condemnation about ignoring the creep of fascism paired with Nemik’s call for even the “smallest act[s] of insurrection” create more than a Star Wars story, but a call to action.

These examples lead to my question: Why would Disney produce such a series? Disney is associated with the media franchise of the U.S. empire and continues to propagate stories that support U.S. ideology, from Pocahontas to The Falcon and the Winter Soldier. As a capitalist enterprise deeply associated with Americana, what does it mean for Andor to be accessed via their streaming services? Tony Gilroy is a successful Hollywood creator, long established in the industry. Perhaps it signals a change in American culture, the hard work of BIPOC activists. Can such literature truly be radical, and what does it mean for radical stories to be disseminated from such a source? It would be too easy to say that perhaps Disney missed the leftist potential of the series—one should not underestimate the producer or the audience. The story of Andor could have been told without the skin of Star Wars, but placing it under the banner of Star Wars places anti-fascist work, abolitionist theory, class solidarity, anarchism and socialism in front of people primed to be supportive of the rebels and at least understand the Empire as evil. Star Wars places these ideas in front of the largest audience possible. Academics, independent artists, and public intellectuals rarely have the opportunity to reach such a large audience or guarantee their work will remain viewable and available. Rather than hope these ideas will be disseminated by professors and activists, trickling down from those who have access, time, and education to analyze and share these theories, the radical work happening on the big stage—rare as it is—should be embraced as a teaching tool rather than disregarded as contaminated or selling out. While it is yet too early to know if Andor will inspire people in any meaningful way, it demonstrates that rebellions are built on more than hope, but communities coming together in solidarity, willing to fight for their freedom.

Works Cited

“The Axe Forgets.” Andor. Disney+, 2022.

Estes, Nick. Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. Verso, 2019.

“The Eye.” Andor. Disney+, 2022.

“Kassa.” Andor. Disney+, 2022.

“One Way Out.” Andor. Disney+, 2022.

“Rix Road.” Andor. Disney+, 2022.

Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Edited by Katherine McKittrick, Duke UP, 2015.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U of Minnesota P, 2018, Kindle Edition.

Posted by: Phoebe Wagner is an author, editor, and academic writing and living at the intersection of speculative fiction and climate change.