This instantly addictive satire lays bare how easily corporate culture turns totalitarian as soon as it gets a chance

It's every manager's dream: employees who can behave 100% professionally and leave their personal problems at the door. Obedient cogs whose entire philosophy of life consists in loyalty to the company. Eager followers who wouldn't dare form close ties with their coworkers and whose aspirations don't aim further than winning a commemorative paperweight. Hyperfocused nonpersons who will never get distracted from their tasks because that's literally the only thing in their minds.

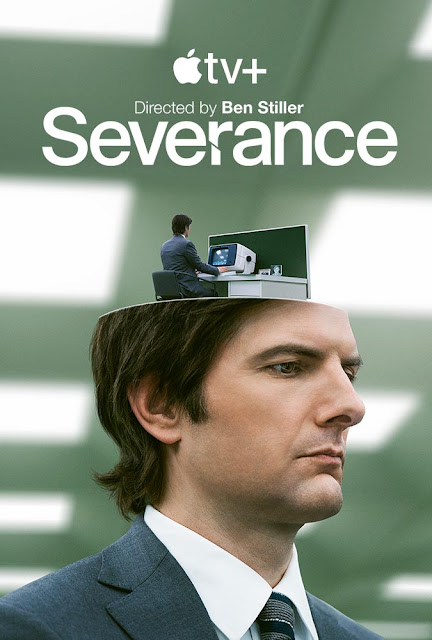

Corporate culture would love nothing more than to achieve that fantasy. Apple TV's new series Severance, created by Dan Erickson and gorgeously directed by Ben Stiller and Aoife McArdle, explores the nightmare that would result if companies could wield complete control over human beings without interference from the outside world.

Severance takes place in a biomedical corporation that subjects its low-level employees to a surgery that separates their memories and identities between their office selves and their outside selves. Every day, they drive to their jobs, enter an elevator, and forget who they are. They work their shifts without any knowledge of their personal lives; while in that state, all they can remember is life inside the company building. At the end of the day, they enter the same elevator and switch back: out in the street, they have no idea what they do for a living or even who their coworkers are.

Not that their jobs make the least bit of sense, mind you. That workplace couldn't be any more ridiculously shady: with its endless featureless corridors, creepy supervisors who won't stop smiling cheerfully, outlandish teambuilding rituals, an obscure internal mythology around the company's founder, an obsessive degree of surveillance, and punitive reeducation worthy of a North Korean prison camp, the surreal environment of Severance presents a heightened version of worrying trends that already exist in real-world companies.

The dangers of organizational totalitarianism and CEO worship have been raising alarms for quite a while now. Our jobs already dominate a big chunk of our lives. The main reason they don't exert more control is fear of worker solidarity, public opinion, and legal retaliation. But in a scenario where no one outside can know what happens inside, where not even we can know what is done to us for eight hours of the day, the corporation won't hesitate to claim every part of us. Once it has control of our actions, it will gladly morph into its own little dictatorship. Let it get its hands on our brains, and it will become a cult.

The fictional company in Severance devotes an amount of effort and resources to singing the praises of its founder that is only one step away from the cult of personality of real-life CEOs. When we think the show can't get any more bizarre, the next episode reveals even darker depths of how much these workers are expected to bow at the feet of the founder. His sayings are holy scripture, his image is a focus for displays of reverence, and his recreated house is a site of pilgrimage. While inside the office, employees are forbidden from reading any literature except the company manual, which is written with such disturbing solemnity that, toward the middle of the season, a mediocre self-help manual smuggled into the building proves life-changing for our protagonist.

Said protagonist is Mark (Adam Scott), a recent widower who applied for a split-memory job so he could forget about his pain for eight hours every day. He only starts to question his routine when a man claiming to be a former coworker contacts him with confusing revelations about what really goes on inside the company.

Honestly, you don't even need a conspiracy theory to smell that something is very wrong about that place. In the office, social interaction is impersonal to the point of loss of humanity. Mark's department spends the workday classifying meaningless numbers, so personal achievements feel empty, and when supervisors recognize them, any enjoyment is clothed in an artificiality that robs it of value. No one knows what their work means; the board of directors are only present as an ominous silence on the phone; the floor layout is deliberately labyrinthine to discourage employees from joining forces; and for whatever reason, there's a goat farm.

Everything about this series sounds incomprehensible. But the cast does a stellar job of grounding the absurdity in real human emotion. Britt Lower, who fulfills the trope of the new hire through whom we learn the rules of this world, takes the story into deep existential terror as her character learns that she is her own worst enemy. John Turturro plays a bootlicking senior employee who gets radicalized when he realizes that his office crush's retirement implies that that version of him will cease to exist. And Patricia Arquette is deliciously menacing as the tyrannical manager with an agenda of her own.

The impressive talent starring in Severance would suffice to recommend it. But the ace up this show's sleeve is its visual language. Both directors convey the claustrophobic life of cubicle workers with an impeccable eye for shot composition. We frequently see Mark sitting alone with half the frame obscured, symbolizing the missing half of his life that he no longer has access to. Although the story appears to be happening in our present time, the office space is designed with a vaguely retro aesthetic that heightens the incongruity of the situation. The end result is simultaneously funny, intriguing, scary, unsettling, sad, relevant, and at its core, intensely human.

With this kind of premise, Severance could easily have rolled down the hill of shocksploitation. But it manages to never lose hold of the humanity at the center of the story. Severance is about the unfair demands of "professionalism" and the increasing pressure to not let our personal issues affect our performance. It's about the frustrations that continue to drive the Great Resignation. It's about private corporations' ongoing attempt to build their own secluded societies, isolated from scrutiny. It's about a system of social relations that makes us complicit in our own exploitation.

On a more intimate level, Severance is about our willingness to rip ourselves apart if that's what it takes to avoid confronting deep pain (there's a subplot about a woman who undergoes the brain surgery to create a separate self who will only exist for the purpose of experiencing childbirth). And, like all great stories, it's about the search for happiness and the amounts of unhappiness we can inflict upon ourselves along the way. Severance is the most important television show of the year, and it will remain culturally significant beyond this decade.

Nerd Coefficient: 10/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.