It's a pity that a film based on Winsor McCay's daring visual innovations ends up looking so conventional and undreamlike

A girl loses her father and processes her grief by oversleeping. An emotionally stunted uncle tries to learn childrearing from Google. The complicated interplay of growth and decay makes the future uncertain and scary. If she wants to grow up and stop retreating into fantasies, she'll have to accept the fact of death, but also help her uncle reconnect with his inner child and dream again.

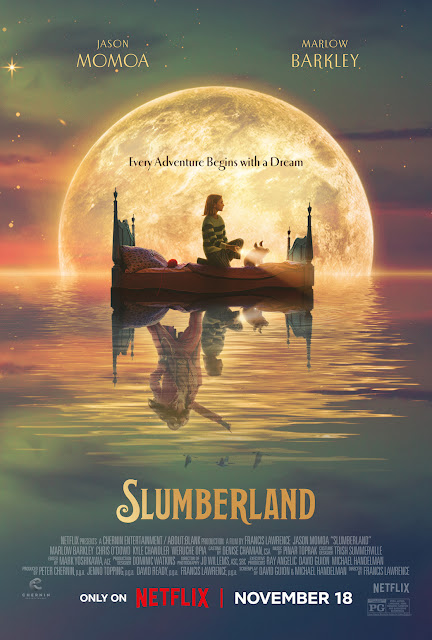

This setup sounds like it should deliver a full emotional experience, bolstered by the metaphoric possibilities of dream language. Unfortunately, Netflix film Slumberland shows us a muted dreamscape that doesn't dare embrace the protean qualities of the unconscious mind. When protagonist Nemo ventures into the land of dreams to look for her father, the place looks too rigid, too rational, built on an oppressively linear logic that makes it less Paprika and more Inception. This does not feel like the dream of a child; it feels like an adult's self-serving memory of what goes on in a child's mind.

I'm usually on the side that magic should have rules, but dreams are the one place where rules should go out the window. The original comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland by Winsor McCay was a visual extravaganza propelled by the whimsical meanderings of the unconscious self, a metafictional experiment where size, perspective, color, movement and even paratext were at the mercy of a child's id. Standing on its own, the film Slumberland is already a faded echo of the wonder of dreams, but when evaluated as an adaptation of McCay's work, it's the worst disservice.

Visual disappointment aside, the film does manage a competent handling of its themes. It at least acknowledges the obvious Freudian connotations of a story where a preteen girl's way of coping with the death of her father is by conjuring an image of thermonuclear sex bomb Jason Momoa, complete with satyr horns and the libido associated with them. His character openly spells it out: "I'm a troubling mix of a father figure and raw masculine power." Accordingly, the film abounds in erotic imagery: on the night she loses her father, Nemo dreams of the destruction of a phallic symbol (a crumbling lighthouse) followed by the threat of a yonic symbol (a swirling hole in the water). Her companion in the adventure (in fantasy terms, a familiar, an extension of the character's soul) is a pig, a traditional icon of unbridled lust. The plot employs a recurring erotic motif of sneaking through forbidden doors and picking locks, and from there the symbolism only gets more intense: the climax requires the protagonist to ride a gigantic goose and put her hand into a watery hole to grab a pearl.

There's a curious parallel between Nemo's psychological journey and that of her uncle, who faces a similar emotional challenge. The plot tells us that he resented his brother for getting married and leaving childish things behind. What this means in Freudian terms is that he responded to his brother's sexual maturation by burying his own immaturity under a mountain of denial. The result is a man with no desires, a repressed loner who sublimates his unacknowledged sexual frustration by pursuing a career where he is in control of the machinery that opens a door.

Regrettably, Slumberland takes all this fertile symbolism and lets it go to waste. As I said before, its idea of the dream world is constrained by unnecessary rules, going to the absurd extreme of adding a bureaucracy that oversees and enforces the proper functioning of dreams. This is the last thing this kind of story needs. The character of Agent Green does provide a measure of tension to chase scenes, but contributes nothing of substance to the plot. When you set a story in the battlefield of the mind, the only antagonist you need is the hero's own conflicting desires. Inside Out understood this. Slumberland burdens its plot with a superfluous antagonist that only serves to overcomplicate a straightforward journey of inner growth.

And yet, straightforward is not what a film about a child's dreams is supposed to be. It ought to be more unpredictable, more fascinating. That's not what we get here. Even for the intended audience, presumably not acquainted with Freudian dream interpretation, Slumberland fails at the basic duty of being exciting. Scenes obviously shot with a green screen are the clearest illustration of this mismanagement of tone: Nemo and her satyr friend burst out at the top of their lungs with explosive exhilaration while the action happening around them is rather slow, bland, underwhelming. Either the CGI department missed a note from the director or Momoa got stuck in Aquaman mode and forgot there are more ways to act.

Slumberland is an adaptation in name only. It has a valuable point to make about the need to make peace with the reality of death in order to grow up, but its delivery of that message falls short of the spectacle and inventiveness of the source material. The experience ends up feeling like one of those dreams you forget in the morning and don't ever miss.

The Math

Baseline Assessment: 6/10.

Bonuses: +1 for thematic cohesiveness, +1 for emotional sincerity.

Penalties:

−1 for painfully obvious dialogue, −1 for Momoa's disastrous Spanish, −1 for somehow making a salsa party look boring as hell, −1 for visual blandness.

Nerd Coefficient: 4/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.