A moving allegory about the urge to survive under impossible oppression

Centuries ago, something came to Earth. Wishing to learn about humanity, it brought human-looking creatures to live among us. They're good at pretending to be human: they can walk and breathe and speak, and even reproduce, but biologically they're very different from us. They were designed to absorb information, most of them by physically consuming the written word, a rare few by consuming the content of the human brain. These scavengers of information were meant to gather as much knowledge about Earth as they could until their creator returned to take them away.

But their creator never returned. So the book eaters and mind eaters were left stranded on our world, physically unable to survive on any other food, psychologically unequipped to integrate into human society. Over the centuries, this secret population has managed to build a culture of its own, complete with laws and traditions, social hierarchies and factions, but the pressures of modern life pose an inevitable threat to the anxious rigidity of their makeshift civilization.

We're introduced to book eater society through the eyes of Devon, a young woman who has spent all her life in an old mansion under the supervision of a dozen uncles and aunts, whose main concern is to find her a favorable marriage. Because, you see, there's a problem with her kind's biology. For some reason, girls are far less common than boys. And that creates a population bottleneck that book eaters have tried to circumvent by setting up a strict system of aristocratic lineages based on patriarchal control over female reproduction. Girls are raised with the utmost care until they can be married off, at which point they become tradeable assets who only exist to give birth. When Devon outgrows her deliberately curated fairy tales and experiences the actual cruelty of her people, she resolves to escape the rules of the game, and become an outlaw.

What makes The Book Eaters a specially interesting read is the allegoric opportunity that this parallel society provides to craft a microcosm of the emergence of the first institutions, and with them, the first dynamics of oppression, in ancient humankind. As we learn about the history of book eaters and the various crises they've had to overcome in order to survive, we get a sense that the author is trying to show us a mirror of how human beings first came up with the notions of family, kinship, marriage, authority, gender roles, obligations, etiquette, ceremony, and propriety. This is one of the most effective tricks in the science fiction arsenal: to speak of the imaginary, only to mean the real. Creating this separate species makes it easier for the author to make incisive observations on human patriarchy and the ways it poisons all social relations.

When a novel has such a strongly defined point to make, the reader may fear it to remain at the level of a transparent moral fable written in a preachy tone. The Book Eaters does not suffer from that pitfall. Far from that. Its dissection of what's wrong with humankind by the indirect way of showing us an alien community rotten at its core goes beyond the well-trodden talking points of contemporary feminism. In fact, this novel makes a fascinatingly intimate study of the mechanisms of domestic abuse, unraveling each of its minute daily assaults and the reasons for the victims' seemingly self-defeating but actually self-preserving survival strategies. Devon's quest to break free from her family's control requires her to twist her way around hundreds of small rules and expectations that, in aggregate, form a suffocating web around her will to live. The author demonstrates a considerably vast comprehension of the ways patriarchy devours its own beneficiaries and stifles the dignity of its sufferers. Upon reading about the extent of Devon's family dysfunction, I had to conclude the author has either first-hand experience with this kind of trauma or spectacularly developed powers of empathy.

(In particular, the interaction between Devon and her brother feels painfully true to life. There were moments I had to take a breath from this novel's disturbingly accurate depiction of how patriarchal tyranny ruins both men and women. Take it from someone who survived such perverse treatment: this is exactly how domestic abuse works, and this is exactly how a victim reacts to keep their independence of mind until a chance of freedom appears. Trust me, I've been there.)

In fitting heroic style, Devon has a source of power that patriarchy cannot understand or counteract. The force that propels her to keep fighting is a simple one: she has somebody to protect. Devon is a mother, and after the system that raised her has taken everything from her, she still has her unshakable sense of responsibility toward her son, and she will move mountains to spare him from the life she had. Her one-woman war against centuries of settled custom is a prime example of the ongoing literary turn from the aristocratic protagonist to the ordinary one. Devon was educated to be a princess, but through pain and fire, she remolds herself into something nobler: a real person.

The Math

Baseline Assessment: 8/10.

Bonuses:

+2 for psychological depth, +2 for originality of concept.

Penalties:

−3 for not adding a trigger warning about domestic abuse.

Nerd Coefficient: 9/10.

POSTED BY: Arturo Serrano, multiclass Trekkie/Whovian/Moonie/Miraculer, accumulating experience points for still more obsessions.

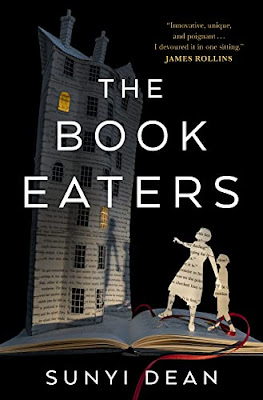

Reference: Dean, Sunyi. The Book Eaters [Tor, 2022].